‘I Thought You Said You Could Skate’: What Funny Girl Teaches Us About Career Conviction

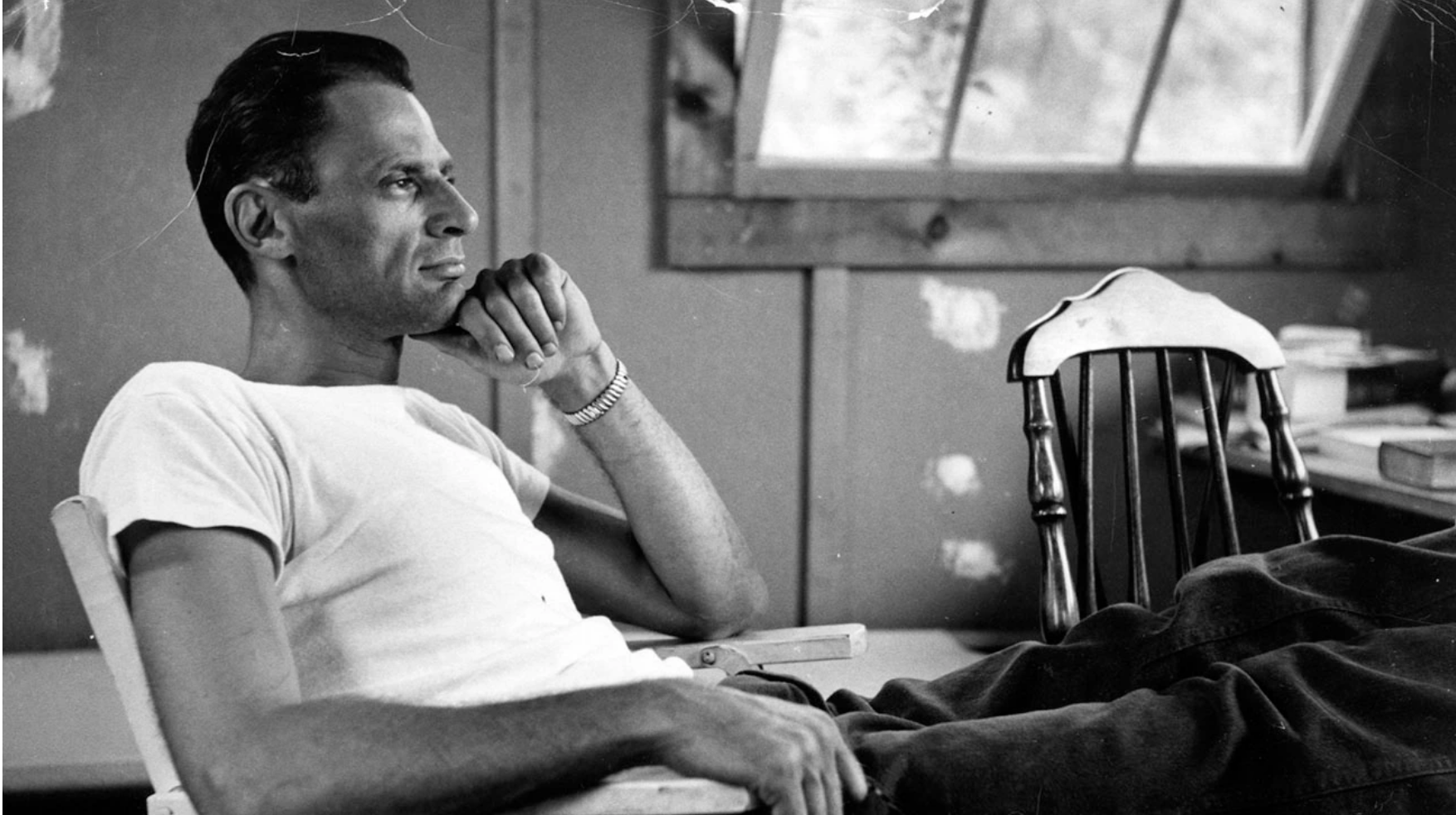

Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl 1968

‘I'd rather be blue over you

Than be happy with somebody else.'

'I'd Rather Be Blue Over You' (B Rose / F Fisher)

‘Funny Girl’ is a 1968 musical rom-com loosely based on the life of comedian Fanny Brice. Directed by William Wyler, it stars a luminous Barbra Streisand in her film debut, reprising a role she performed previously on Broadway.

We are in New York in the early years of the twentieth century. Fanny is a stage-struck young Jewish woman whose mother runs a saloon on the Lower East Side. She gets a part in the chorus line of a vaudeville dance troupe at Keeney’s Oriental Palace. But with her unconventional looks she feels she doesn’t quite fit in.

'I'm a bagel on a plate full of onion rolls.’

What’s more, Fanny can’t dance. Fired by Keeney after a disastrous audition, she is quizzed about her ambition by dance coach Eddie.

Eddie: You’re no chorus girl. You’re a singer and a comic… So why’d you try out for the chorus?

Fanny: Cos that’s what you were looking for. If you were looking for a juggler, I’d have been a juggler. Just got to get on stage somehow.

Fanny is bemused by the fact that Eddie gave her a chance in the first place.

Fanny: How come you hired me?

Eddie: Because you wanted it so much.

Eddie conspires with Fanny to try her luck again, this time in a roller skating act.

Eddie: Are you sure you can roller skate?

Fanny: Can I roller skate?

In purple and green velvet-striped shift dress, with matching hat, tights and skates, Fanny takes to the stage. She teeters and totters, and careers out of control - crashing into the scenery, bumping into the other skaters, almost toppling into the orchestra pit. She causes chaos everywhere she rolls.

Eddie: I thought you said you could skate!

Fanny: I didn’t know I couldn’t.

Fanny’s performance is a disaster. But the audience finds it totally hilarious.

Her comedy act at Keeney’s gets her noticed, and six months later she is offered a role in the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway. Despite her inexperience, she continues to display the bloody mindedness that earned her her first break. In her debut show, reluctant to perform a romantic song straight, she disobeys management and gives it a comic twist. Subsequently she insists on singing her own songs. Such grit and determination accelerate Fanny’s journey to becoming a top Broadway star.

'Who is the pip with pizzazz?

Who is all ginger and jazz?

Who is as glamorous as?

Who's an American beauty rose,

With an American beauty nose,

And ten American beauty toes?

Eyes on the target and wham

One shot, one gun shot and bam!

Hey Mister Keeney

Here I am.’

'I'm the Greatest Star’ (J Styne / B Merrill)

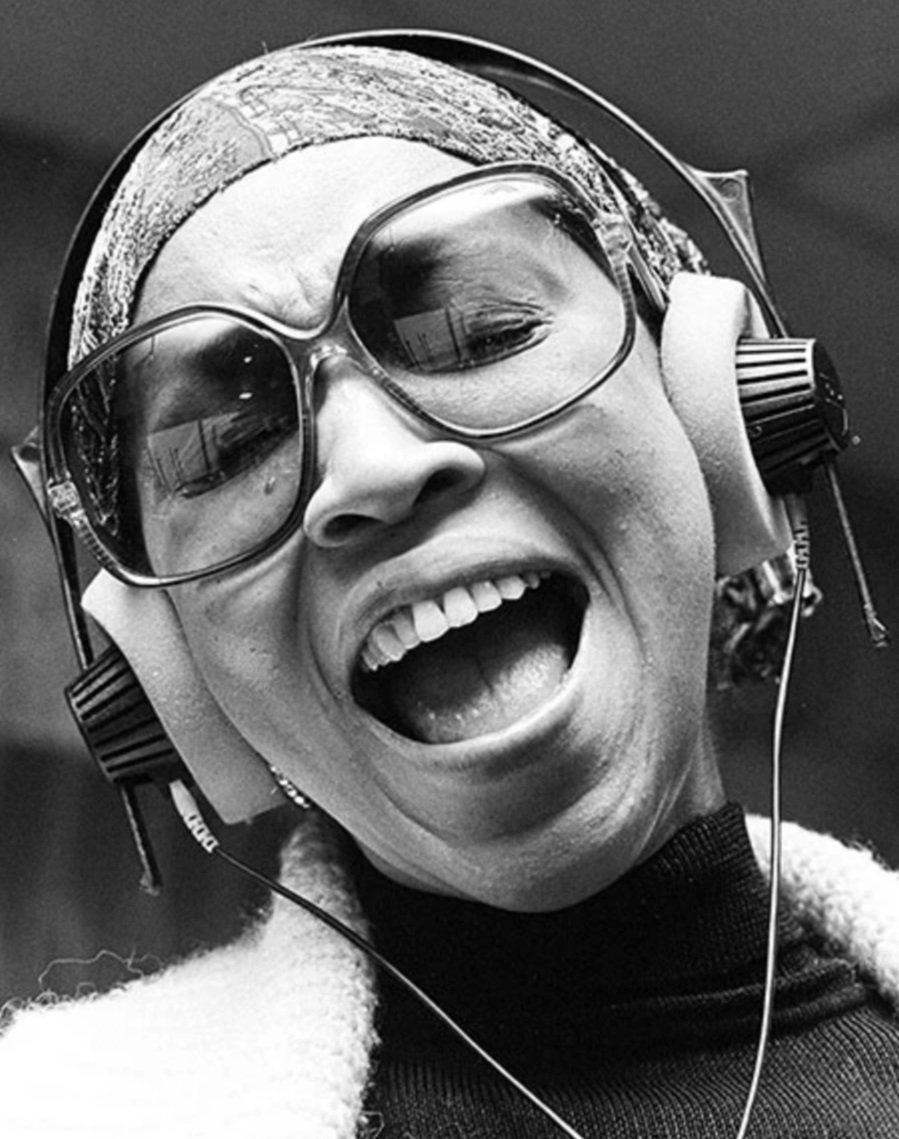

‘Funny Girl’ became the highest-grossing film at the US box office in 1968, and it received eight Oscar nominations. Streisand won Best Actress, tying with Katharine Hepburn. Though it was her first movie, Streisand took a hands-on interest in how it was shot. At the wrap party Wyler gave her a director's megaphone in mock recognition of her contribution.

Maybe Streisand was channelling Fanny Brice. Indeed we can all take career lessons from the legendary Broadway star.

Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl. Photo: Columbia.

We may shy away from certain roles and challenges because we’re concerned about our inexperience. We may be constrained by our fear of failure, by our modest estimation of our own abilities. But Fanny suggests that we should overcome our doubts and dithering; that, setting our sights on our ultimate goal, we should seize every opportunity with complete conviction.

Of course, we may find out that we can’t skate. But perhaps we’ll discover another talent in the process.

Fanny’s ascent to the top is not completely seamless. She becomes attached to a charming but hopeless gambler (played by Omar Sharif). Nonetheless she navigates her romantic dilemmas with the same resolve and tenacity with which she approaches her career.

As Barbra Streisand so compellingly puts it: ‘Don’t rain on my parade!’

'Don't tell me not to fly,

I've simply got to.

If someone takes a spill

It's me and not you.

Who told you you're allowed

To rain on my parade?’

‘Don’t Rain on My Parade’ (J Styne / B Merrill)

No. 392