The Persistent Positivity of Mavis Staples: ‘Just Another Soldier in the Army of Love’

‘I’m not gonna stop. I was there. I’m still here. I’m a living witness.’

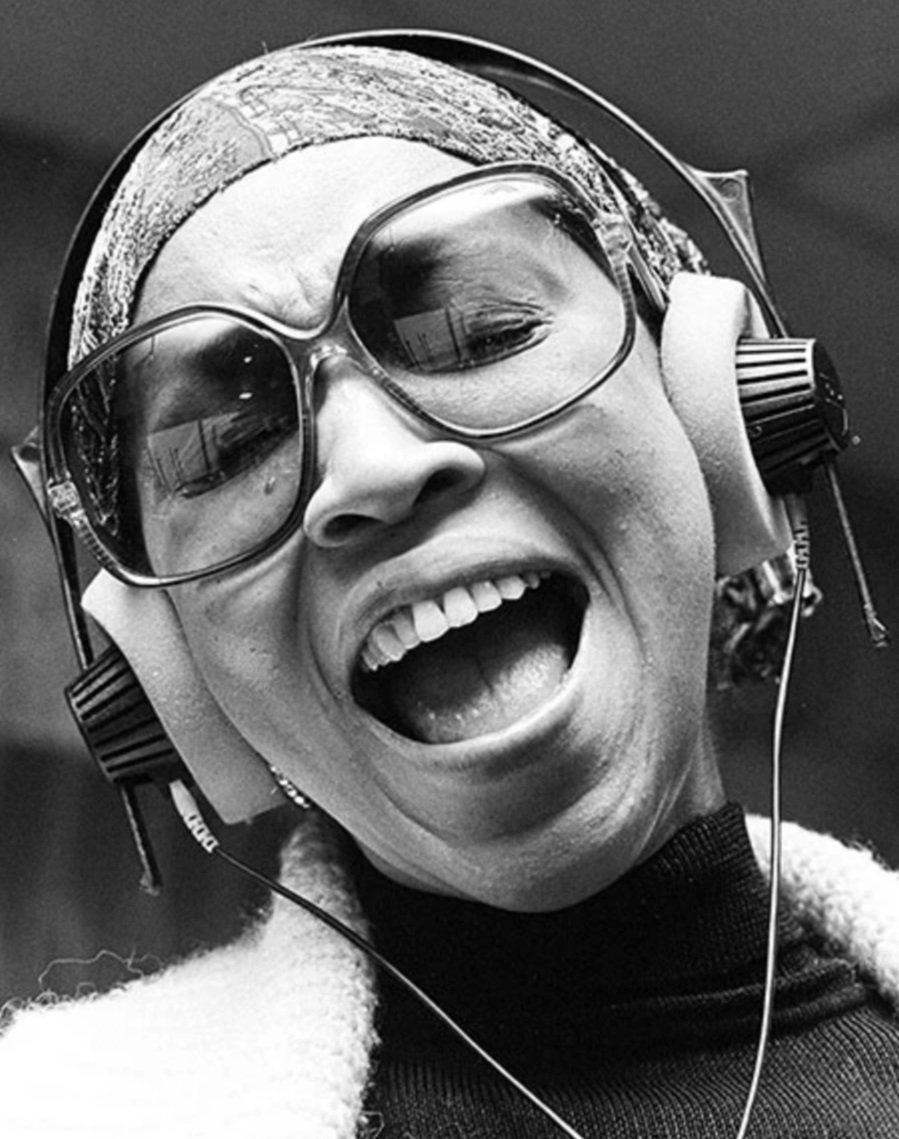

I recently attended a performance by 82-year-old Mavis Staples, lead vocalist of the legendary Staple Singers. I followed this up by watching a moving documentary about her life and career: ‘Mavis!’ (2015, written and directed by Jessica Edwards)

'The devil ain't got no music. All music is god's music.’

The Staple Singers pioneered a hybrid of gospel, folk and soul that combined melodic sweetness with a gutsy guitar sound, raw vocal storytelling and an urgent message. With their heartfelt ‘freedom songs’ they took a leading role in the civil rights struggle. And to this day Mavis Staples sustains their calls for progress with resolute positivity.

‘We’ve come to you this evening to bring you some joy, some happiness, inspiration and some positive vibrations.’

Let’s consider how Mavis and the Staple Singers can ‘take you there.’

'I know a place

Ain't nobody cryin’,

Ain't nobody worried,

Ain't no smilin' faces

Lyin' to the races.

Help me, come on, come on.

Somebody, help me now.

Help me,

Help me now.

Oh, let me take you there.

Oh-oh! Let me take you there!’

The Staple Singers, ‘I’ll Take You There’ (A Isbell / A Hardy)

1. ‘Family is the Strongest Unit in the World’

Born in 1914, the youngest of 14 children, Roebuck ‘Pops’ Staples grew up on a cotton plantation near Drew, Mississippi. Having learned to play guitar from local bluesmen, he dropped out of school to sing with a gospel group. In 1935 he married Oceola Staples and they moved to Chicago where Pops found work in meatpacking, construction and steel.

The couple had four children - Cleotha, Pervis, Mavis and Yvonne – who grew up together on 33rd Street on the South Side, a melting pot of musical talent. Sam Cook, Curtis Mayfield and Jerry Butler all lived nearby and the Staples house became a social hub.

‘Everybody would come to our backyard because Mamma would make home-made ice cream, spaghetti, coleslaw. So they knew this was a party at the Staples backyard.’

Family meant everything to Pops.

'Pops always taught us that family is the strongest unit in the world. If you stick with your family, nobody can break you, nobody can harm you. You'll always have your family.’

2. ‘Sing What You Feel in Your Heart’

Pops set about giving the young Staples siblings their musical education.

‘Pops called us kids into the living room. He sat us on the floor in a circle and he began giving us voices to sing that he and his sisters and brothers would sing when they were in Mississippi.’

In 1948 Pops formed the Staple Singers, and they took to performing in local churches and on the radio.

Mavis had a deep, gritty voice that resonated powerfully with Pops’ blues guitar.

‘People would say, ‘That’s not a little girl… It’s got to be a man or a big fat woman.’’

Mavis ignored the comments and sang with total conviction.

'I'm just singing what I feel in my heart.’

In 1952 the Staple Singers signed a professional contract and 1956’s ‘Uncloudy Day,’ their first hit, became the first gospel song to sell a million records.

'They tell me of a home far beyond the skies

And they tell me of a home far away.

They tell me of a home where no storm clouds rise

They tell me of an unclouded day.’

The Staple Singers, 'Uncloudy Day'

The Staples Singers in the late 50s (left to right) Pops, Cleotha, Mavis and Pervis. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives

3. ‘If You Ain’t Shouted the People, You Ain’t Done Shit.’

Mavis learned to use the power of her voice to excite raw emotions in congregations. In the gospel world this is called shouting.

‘If you ain’t shouted the people, you ain’t done shit.’

Audiences would scream and dance in the aisles, and some would be so overwhelmed they had to be carried out by the ushers. Staple Singers concerts were exhilarating experiences.

‘Shouting is not a bad thing. When you shout and let it out, you gonna feel better.’

4. ‘Everybody Don’t Love You’

When Mavis graduated in 1957, Pops took the Staple Singers on the road, marketed as ‘God's Greatest Hitmakers.’ But touring exposed the young family to the indignities of the segregated South.

‘Pops explained to us: ‘Now listen y’all, it’s not like you’re in Chicago. Everybody don’t love you.’’

They were barred from many hotels and restaurants, and they had to learn to be resilient in the face of racist abuse.

‘White kids would try to run us off the highway. But Daddy wouldn’t take it. He’d go right back into them. He took enough of that when he was a boy.’

One Sunday while on tour Pops took the family to hear Dr Martin Luther King preach at his church in Montgomery, Alabama. Pops was hugely impressed, and later announced:

‘I like this man’s message. I really like his message. And I think, if he can preach it, we can sing it.’

The Staple Singers began performing ‘message’ music. Through compelling songs like ‘Freedom Highway’, ‘Why? (Am I Treated So Bad)’ and ‘When Will We Be Paid?’ they became the musical voices of the civil rights movement.

5. ‘Reflect and Effect the Culture’

As the ‘60s progressed, Pops sought to expand the band’s audience by performing in jazz clubs and at folk festivals. This exposed them to music from other genres, and led to them covering contemporary hits with positive themes - by the likes of Bob Dylan, Stephen Stills and Joan Baez.

Inevitably the evolution in style prompted criticism from the traditional gospel community. But the family were insistent that they were staying true to the spirit of their faith.

‘You know gospel ain’t nothing but the truth, and we’re telling the truth in our songs.’

In 1968 the Staple Singers signed to Stax Records. Working with producers Steve Cropper and Al Bell, and with musicians from Booker T and the MGs, their sound became more soulful. This led to more success, and to the hit singles ‘Respect Yourself’ and ‘I'll Take You There.’

Bell observed the special place that the Staples had in the music industry at that time:

‘They say that art in many instances is either a reflection of what’s going on in your culture or in society, or it effects, impacts what’s going on. Staples were doing both.’

'If you disrespect anybody that you run into,

How in the world do you think anybody's supposed to respect you.

If you don't give a heck about the man with the bible in his hand,

Just get out the way, and let the gentleman do his thing.

You're the kind of gentleman that wants everything your way,

Take the sheet off your face, boy, it's a brand new day.

Respect yourself.

If you don't respect yourself,

Ain't nobody gonna give a good cahoot,

Respect yourself.’

The Staple Singers, ‘Respect Yourself’ (L Ingram, M Rice)

6. Only Stop Singing When You’ve Nothing Left to Say

Sadly Stax was declared bankrupt in1975. The Staple Singers signed to Curtis Mayfield's Curtom label and scored another hit with ‘Let's Do It Again.’ They also memorably performed ‘The Weight’ with The Band in their film ‘The Last Waltz.’ However, with the arrival of disco in the late ‘70s and the growing taste for more heavily produced sounds, the group’s popularity declined.

Gradually time has taken its toll. Pops passed away in 2000, followed by Cleotha and Yvonne. When Pervis died in 2021, Mavis became the last soul survivor.

‘It’s because of you, Pops, that I’m standing here today. And I tell you, you laid the foundation and I am still working on the building.’

Mavis, who made a couple of fine solo albums in 1969-70, has continued to record brilliant music, on her own and with collaborators. She has no intention of packing it in.

‘People always asking me when am I going to retire. I don’t care to retire….I’ll stop singing when I have nothing left to say. And that ain’t gonna happen.’

I was particularly struck by Mavis’ dedication to the cause; by her youthful enthusiasm and her ageless conviction that there is still work to be done.

‘My mind is made up and my heart is fixed and I just refuse to turn around. I have come too far. And I’m determined to go all the way until Dr King’s dream has been realised… And if y’all don’t see me here singing, look for me in heaven…I’ll be walking those streets of gold and singing around god’s throne.’

Mavis and her family teach us that a desire for progress and a commitment to change cannot be lightly held or casually worn. Rather they must come with passion and action; hard work and a hard edge.

As she sang in one of the Staple Singers’ greatest songs, she’s ‘just another soldier in the army of love.’

'Now hate is my enemy. I gotta fight it day and night.

Love is the only weapon with which I have to fight.

I believe if I show a little love for my fellow man

Then one day I'll hold the victory in my hand.

That's why I'm just another soldier in the army of love.’

The Staple Singers, ‘I’m Just Another Soldier’ (R Jackson, H Banks)

No. 383