Beg, Steal or Borrow: Ingres and Picasso on Imitation and Inspiration

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 'Madame Moitessier'

'You can’t steal a gift. Bird [Charlie Parker] gave the world his music, and if you can hear it, you can have it.'

Dizzy Gillespie

I recently attended a very small exhibition.

‘Picasso Ingres: Face to Face’ at the National Gallery, London (until 9 October) comprises just two paintings: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ 1856 portrait of Madame Moitessier, and Pablo Picasso’s 1932 work, ‘Woman with a Book.’

These two great portraits share the same pose and composition. But they are radically different. Seeing them together, side-by-side, one gets the opportunity to consider the issues of imitation and inspiration.

‘Who is there, among the greats, who has not imitated? Nothing is made with nothing…’

Ingres

Ingres accepted the commission to paint Ines Moitessier, the young wife of a wealthy banker in 1844. But it took him 12 years to finish it. Work was delayed by the sitter having a baby and the artist losing his spouse. He also hesitated over the best pose and the most appropriate gown.

Eventually Ingres, a devoted classicist, settled on a composition inspired by a Roman fresco from Heraculaneum: it depicted the goddess Arcadia seated with her head propped on one hand.

Roman fresco from Heraculaneum, Hercules finding his son, Telephos

Madame Moitessier regards us with a finger of her right hand resting casually on her temple. She sits on a red satin chair and wears a dress of white Lyon silk, patterned with fragile flowers, decorated with bows and brocade. Her skin is pale as alabaster, though there is a slight rosy glow on her cheeks. Her expression is sensitive, serene, imperious and knowing. She is confident in her position in society, her rank confirmed by the expensive jewels pinned to her frock and hanging from her neck and wrist; by the Chinese porcelain and silk fan in the background. There is a mirror positioned behind her and we see her profile in reflection. It is if we can glimpse her interior as well as her exterior self.

Picasso saw Ingres’s painting of Madame Moitessier in Paris in 1921, when it was put on public display for the first time. It must have left an abiding impression. When, over 10 years later, he embarked on a portrait of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter, he asked her to adopt the same pose as Madame Moitessier.

As in Ingres’ portrait, Walter sits with her right arm resting on a chair, her hand splayed at the side of her head and a finger to her temple. And there is a blush on her cheeks. But there are also dramatic differences between the images. Where Ingres’ work is flawlessly realistic, finely detailed and smoothly finished, Picasso employs avant-garde cubist techniques and applies his paint in thick daubs of bold colours. Walter’s dress is reduced to flattened panels of vivid blue and white with a pinwheel pattern, and she holds an open book rather than a fan. Her face is seen both in profile and front view, her skin and hair are mostly green, and her breasts are exposed. There is a mirror behind the sitter, but in this instance the identity of the figure in profile is unclear. Could it be the artist himself?

The two paintings prompt us to reflect on creative inspiration.

As Ingres was inspired by an ancient Roman fresco, so Picasso was inspired by a portrait he once saw at an exhibition. Both artists borrowed elements of pose, setting and composition. But both also made significant departures from the source material, making their work very much their own. Each painting echoed the other without copying it.

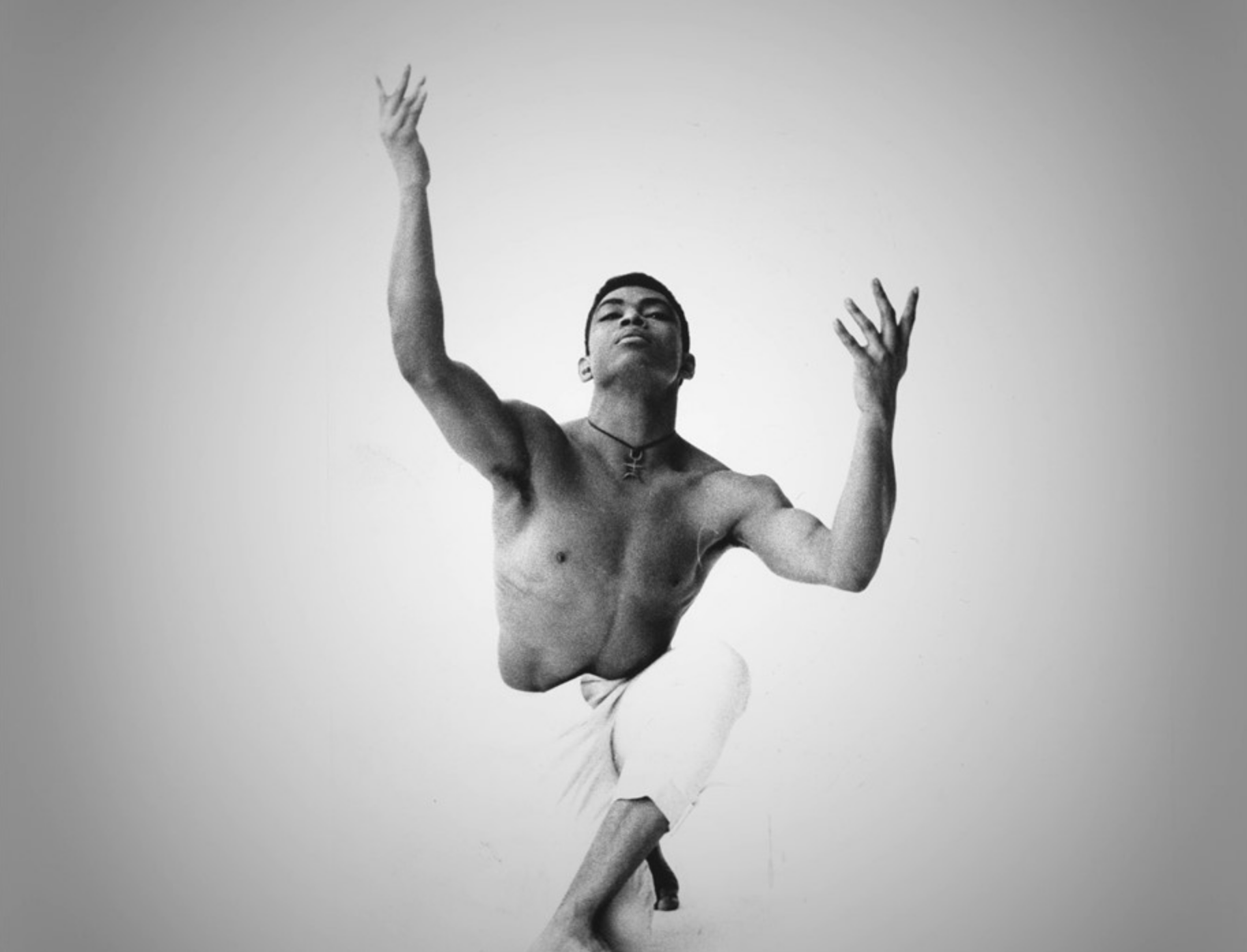

Pablo Picasso, ‘Woman with a Book’

Many years ago, when I was quite young in the business, a Creative Director explained to me that he approached every brief by thumbing through old D&AD annuals. He would randomly search for sparks and stimulus from historic award winners. At the time I thought this a rather derivative, and perhaps even cynical, approach. It suggested that every task had been set before, and every solution had already been written.

'If you steal from one author, it’s plagiarism; if you steal from many, it’s research.'

Wilson Mizner

Perhaps I was wrong. Ideas need catalysts. We must open ourselves up to prompts and provocations from all manner of sources. And then we must take a leap.

When considering this theme, Apple founder Steve Jobs often quoted Picasso:

‘Good artists copy, great artists steal.’

However, it transpires that this thought derived, not from the great Spanish artist, but from a great Anglo-American poet:

‘Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.’

TS Eliot

Maybe it doesn’t matter whose idea it was. As the French film director Jean-Luc Godard observed:

'It’s not where you take things from - it’s where you take them to.'

'I look at you and I see

What I've been looking for.

Now it's very clear to me

We should be together.

You make me feel I could reach

For the impossible.

And knowing how much you care,

I'll be there forever.

You know I'll beg,

Steal or borrow,

To give you sunny days.

And in a hundred ways

I'll bring you love.’

The New Seekers, ‘Beg, Steal or Borrow’ (T Cole, S Wolfe and G Hall)

No. 382