The Unwritten, the Unspoken and the Unspeakable: Arthur Miller’s ‘Fruitful Conflicts’

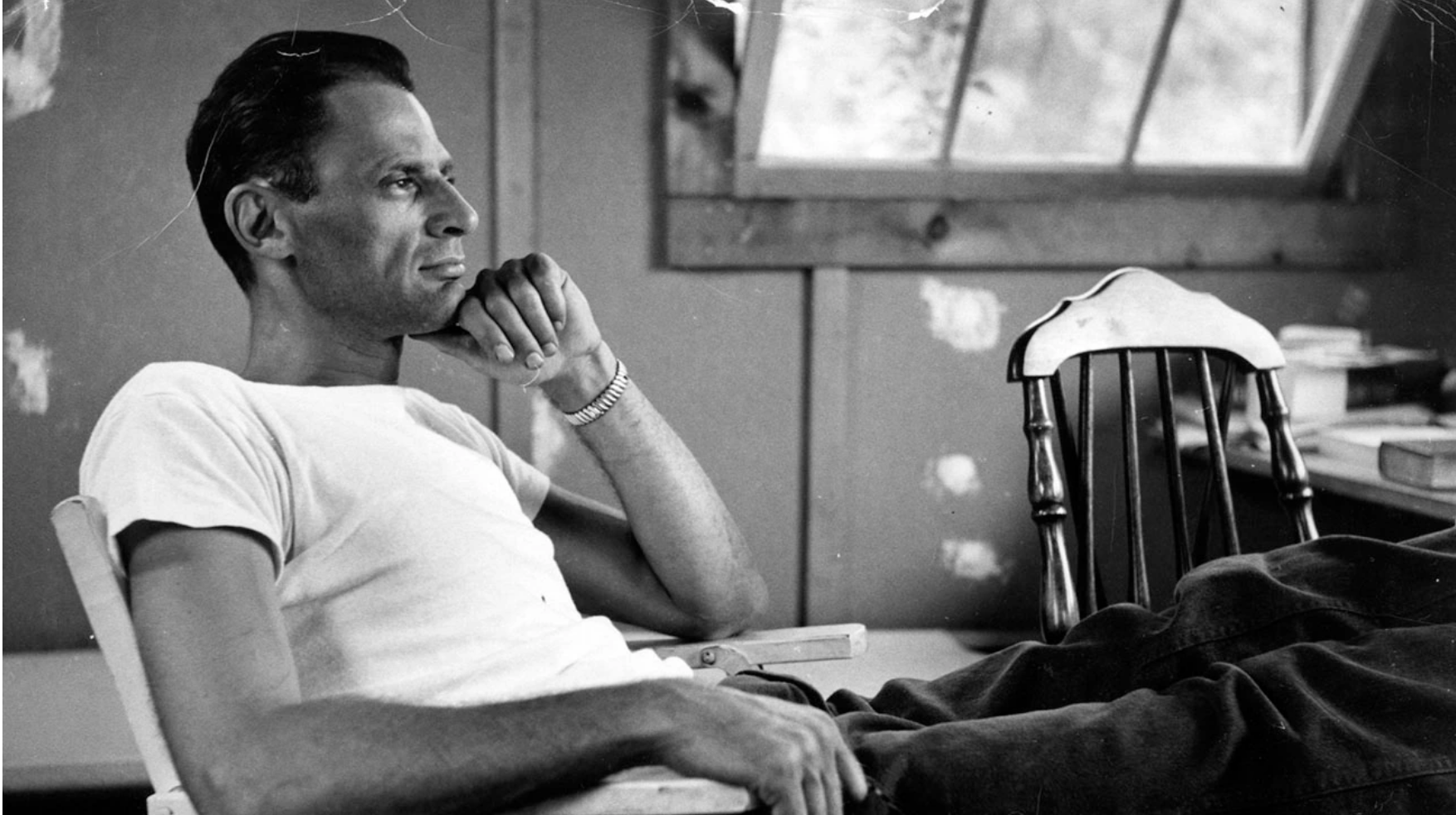

Rebecca Miller filming Arthur Miller in wood shop

Courtesy of Telluride Film Festival

‘I think it’s a process of approaching the unwritten and the unspoken and the unspeakable. And the closer you get to it, the more life there seems to be.’

Arthur Miller

I recently watched the fine 2017 documentary ‘Arthur Miller: Writer.’ It was directed by Rebecca Miller, the daughter of the great American playwright, and based on interviews she conducted with him over many years in the family home in Roxbury, Connecticut. It is therefore a more intimate and informal portrait than a conventional film biography.

We see an elderly Miller engaged in cooking and carpentry, gardening and pond management. He prepares a chicken for dinner, makes a coffee table and walks the dog. And in amongst all this domestic administration, he reflects on a life spent seeking truth.

‘What a real playwright has to do is to say to the audience, in effect: ‘This is what you think you’re seeing in life every day.’ And then to turn that around and say: ‘This is what it really is.’’

As the documentary revisits the writer’s key works, it becomes clear that, with each play or screenplay, Miller was confronting the challenging realities he observed in the world around him, in his relationships and in himself.

1. Confronting His Father

Miller was born in 1915, to Polish-Jewish parents, in Harlem, New York. His father owned and managed a business that manufactured women's clothing and employed some 400 people. His mother was a cultured woman with a lust for life. And Miller grew up in comfort on 110th Street in Manhattan.

The family lost almost everything in the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

‘First the chauffeur was let go, and the summer bungalow was discarded, the last of her jewellery had been pawned or sold. And then another step down – the move to Brooklyn.’

Miller was obliged to deliver bread and wash dishes to pay for his college tuition. He saw his father diminished, retreating into himself. And he looked on as his parents’ relationship decayed.

‘I could not avoid awareness of my mother’s anger at this waning of his powers – a certain sneering contempt of him that filtered through her voice.’

Miller became acutely conscious of the impact that exterior events have on interior lives.

‘I contracted the idea that we are very deeply immersed in the political and economic life of the country and of the world; and that these forces end up in the bedroom, and end up in the father and son, father and daughter arrangements.’

No surprise perhaps that, when Miller wrote his first play, ‘No Villain,’ while studying at the University of Michigan, it was a portrait of a New York immigrant family endeavouring to manage a garment business through the Depression.

‘No Villain’ won Miller a prize and set him on his way to becoming a playwright. His first major success came with 1947’s ‘All My Sons.’ Based on a true story, it related how a thriving businessman with a happy family life is discovered to have been manufacturing faulty aircraft parts during the war.

Miller saw in this theme a means to puncture post-war American euphoria; to challenge the complacent view that all was well with the world. And he also recognised an opportunity to further explore the relationship between fathers and sons.

In ‘All My Sons’ Miller played out the disputes with his father that he had never been able to have face-to-face.

‘You know, the truth of the matter is that I never had an argument with my father. That was part of the problem. We could never come to a fruitful conflict. So it took my work to do that.’

2. Confronting the American Dream

Miller’s next and greater triumph came a few years later. It started with a couple of lines:

‘It’s all right. I came back.'

Convinced that these words could lead to something compelling, but uncertain how to proceed, Miller resolved to take his mind off things. He set about building a small studio at his home in Roxbury.

'When I closed in the roof it was a miracle, as though I had mastered the rain and cooled the sun. And all the while afraid I would never be able to penetrate past those first two lines.'

Then, suddenly, inspiration struck. In just one night, Miller wrote Act I of ‘Death of a Salesman.’

'When I lay down to sleep I realized I had been weeping – my eyes still burned and my throat was sore from talking it all out and shouting and laughing.'

‘Death of a Salesman’, which premiered to great acclaim on Broadway in 1949, examined the tarnished American Dream - the psychological damage done to those whose wholehearted belief in aspiration and achievement is disappointed by bitter experience. Its hero Willy Loman is haunted by lies – society’s, his employers’ and his own.

‘In Willy the past was as alive as what was happening at the moment- sometimes crashing in to completely overwhelm his mind.’

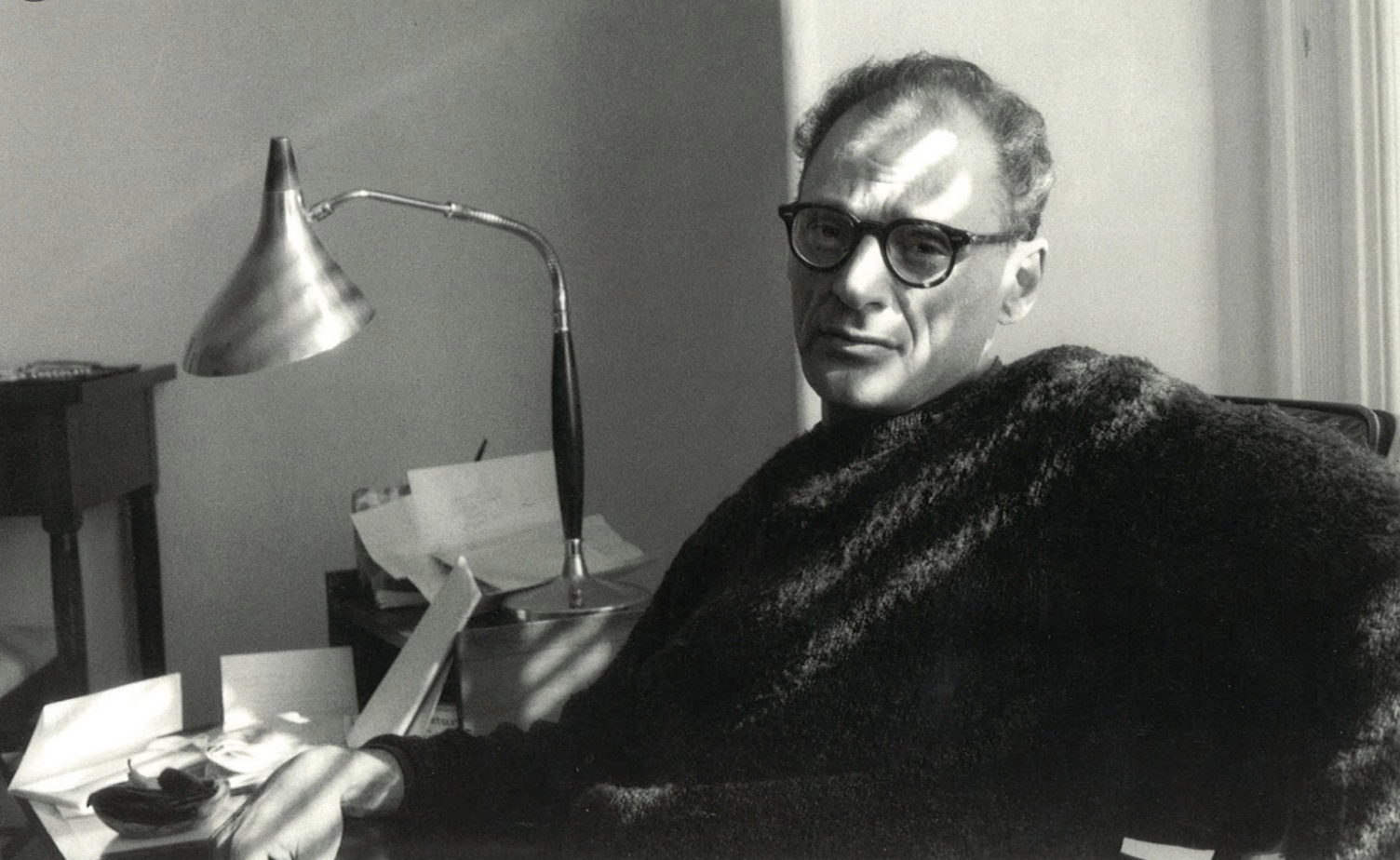

Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller, in Reno, Nevada, in 1960.

Photograph by Inge Morath / Magnum

3. Confronting Power

Miller had developed a close friendship with Elia Kazan, the gifted director of ‘All My Sons’ and ‘Death of a Salesman.’

In 1952, with the United States in the grip of the ‘Red Peril’, Kazan appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and named eight theatre colleagues who had been fellow members of the Communist Party.

Miller was shocked and disappointed. He refused to speak to Kazan for the next ten years.

‘You got the feeling that there was no value anywhere; that we were all the subject of Big Power.’

Miller saw parallels between HUAC’s obsessive enquiries and the witch-hunt that took place in Salem, Massachusetts back in 1692. And so he penned ‘The Crucible,’ which opened on Broadway in 1953. The play explored how quickly social order can deteriorate when intolerance, hysteria and hypocrisy take hold.

In 1956 Miller was himself summoned to appear before the committee. He gave them a detailed account of his own political activities, but refused to volunteer the names of friends and colleagues. He was found guilty of contempt, fined and given a suspended prison sentence.

‘We are a country of entertainers. You’ve got to be entertaining. Even the fascists have to be entertaining.’

Montgomery Clift, Marilyn Monroe, Eli Wallach, Arthur Miller, John Huston, Clark Gable, The Misfits

4. Confronting His Own Passions

Miller had married Mary Slattery in 1940. A fellow student at the University of Michigan, she encouraged him to write, and supported him before his plays became successful. Together they raised two children.

In 1951 Miller had a brief affair with the film star Marilyn Monroe and they remained close. His passion for her became all-consuming.

‘It is as though we were born the same morning, when no other life existed on this earth.’

Miller divorced Slattery and married Monroe. And he channelled his turbulent emotions into 1956’s ‘A View from the Bridge’ - a play concerned with desire, appetite and shame; about a man struggling with a compulsion that will destroy him.

‘The best work that anybody ever writes is the work that is on the verge of embarrassing him.’

In 1960 Miller wrote the screenplay for ‘The Misfits’, which starred Monroe. It was a sad tale of lonely hearts, lost souls and the fading West.

Miller clearly regarded Monroe herself as something of a tragic misfit. Indeed in the film he had Clark Gable address her with a line he had uttered during their courtship.

'I think you're the saddest girl I ever met.'

During the production their relationship was troubled, and shortly before the film's premiere in 1961, the couple divorced. Monroe died the next year, following a drug overdose.

Two years later Miller wrote the deeply personal ‘After the Fall.’ A man reviews the failure of his marriage to a star who suffers from addiction issues and ultimately commits suicide.

This was all too raw for critics and audience alike, and the play was not a success.

‘I guess every artist has a tendency to throw himself into the world – to see if he floats.’

5. Confronting Disappointment

With 1968’s ‘The Price’ Miller finally addressed his Jewish heritage. It was a play about the corrosive effect of financial strife on family relationships; about a family at war with itself. And again it drew on Miller’s own experiences of the Depression.

‘The Price’ did well critically and commercially. But Miller did not feel at ease with the mood of the times. He began to lose his faith in the capacity of theatre to act as a forum for debate, as a vehicle for change.

‘You got the feeling it didn’t matter any more. The whole game was not worth the candle. So you made people feel this or feel that, or laugh or weep. So what’s the hell the difference? What’s the point of it all?’

Miller carried on writing, but had to come to terms with the reality of his diminished popularity and relevance.

At least he was content with his home life. In 1962 he had married photographer Inge Morath who had worked on the production of ‘The Misfits.’

‘A play always has two lives, the written one and the one lived. The latter, thankfully, is happy.’

Miller and Morath remained together until her death in 2002. Miller died in 2005 at the age of 89 at his home in Roxbury.

‘The big job is not to make simple things complicated, but to make complicated things comprehensible. In other words, I’m the guy who goes around and says: ‘What is really going on here?’’

Miller spent a lifetime confronting difficult truths and harsh realities. He could be as tough on himself and his own relationships, as he was on the systemic injustices he saw in American society. He suggests that creative people should use their talent to examine ‘the unwritten, the unspoken and the unspeakable’ – to produce ‘fruitful conflicts.’

Perhaps we too should address: the truth of the family ties that bind us; the corrosive effects of our ambition; our attitude to power and authority; the compromises we make in the name of passion; the disappointments of age, as the world passes us by.

‘The truth, the first truth, probably, is that we are all connected, watching one another. Even the trees.’

[Arthur Miller’s ‘The Crucible’ runs at the National Theatre, London from 14 September to 5 November.]

'I'm not gonna get too sentimental

Like those other sticky valentines.

'Cause I don't know if you are loving somebody.

I only know it isn't mine.

Alison, I know this world is killing you

Oh, Alison, my aim is true.’

Elvis Costello, ‘Alison'

No. 386