The Net Curtain Strategist

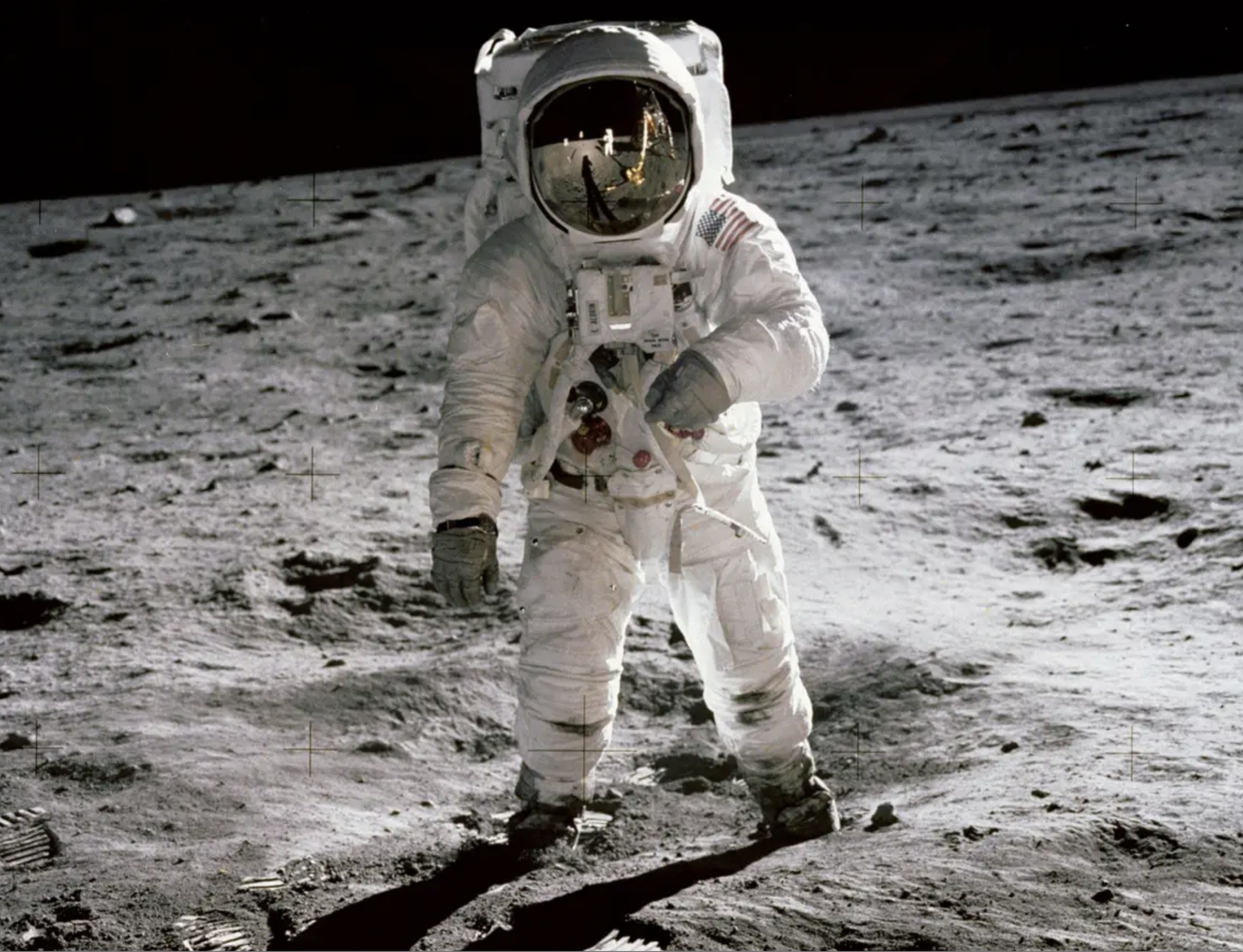

Refaela Revach Looking out the window Painting

My childhood home in Romford looked out onto Heath Park Road, a relatively busy suburban street, lined with neat front gardens and pebble-dashed, semi-detached houses.

Over the rain-sodden school holidays my brother Martin and I often found ourselves stuck indoors, and our mother would invent tasks to occupy our time.

For one such assignment, she located us on stools by the living room window, supplying paper, pencils and a glass of squash. She then asked us to record the different colours of the cars passing by the house, in order to establish which shade was most popular.

‘Blue!’ ‘Red!’ ‘Blue!’ ‘Yellow!’

Eagle-eyed and attentive, with every new vehicle we added another stroke to a five-bar gate, setting about our objective with high seriousness.

I can’t say it was a particularly challenging or instructive exercise. Sometimes a metallic finish or striped van prompted a bit of debate. Sometimes the cars came past in a mad flurry all at once. And this being the ‘70s, most of the cars were just blue or red. (The black automobile was a rare sight back then.)

Nonetheless, we spent many happy hours at that bay window.

Our monitoring of the traffic on Heath Park Road was given an extra frisson by the fact that, like secret agents, we were working unnoticed and out of sight. Most homeowners back then protected their privacy by hanging net curtains. These enabled residents to see out, but prevented passers-by from seeing in – a phenomenon quite beyond my crude understanding of science.

Over recent years the Planning discipline has grown in respect and recognition in the broader Agency community. We celebrate great insights and approaches. We cultivate our own flamboyant presentational styles. We lionize the best practitioners.

This is all of course to the good.

I would nonetheless suggest that for the most part good strategists work as if behind net curtains. Largely anonymous, quietly observing, seeing without being seen, they are unobtrusive and understated. They are also mindful of avoiding the Observer Effect, by which the act of measurement disturbs the object measured.

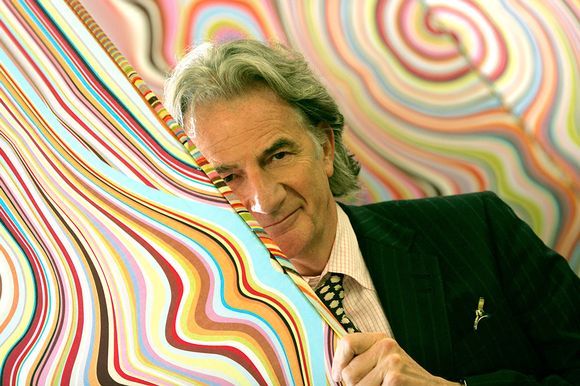

I am reminded that the great John Bartle, one of the BBH Founders, argued that Planners should contribute ideas without claiming authorship; that there is more chance of collective success if individuals are not striving for acknowledgement; that the best strategists are generous at heart.

‘Success has many parents, failure is an orphan - be happy to let others take the credit and success is more likely.’

John Bartle

I have occasionally wondered whether it was my mother’s car-monitoring exercise that set me on the path to strategy and research. Perhaps. But I’m not sure I ever really excelled at quantitative data and analysis.

'Every day now I can feel you watching me from afar,

And you've been leaving those love letters on my car.

So now I wonder, why you're so into me, in such a way

That you've got to take your spare time to chase after me.

What a shame.

So you like what you see?

Hey, you better put a hold on me.

So you like what you see?

Girl, you better put a hold on me.’

Samuelle, 'So You Like What You See’ (Samuelle, Foster & McElroy)

No. 470