Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Breaking Down the Walls

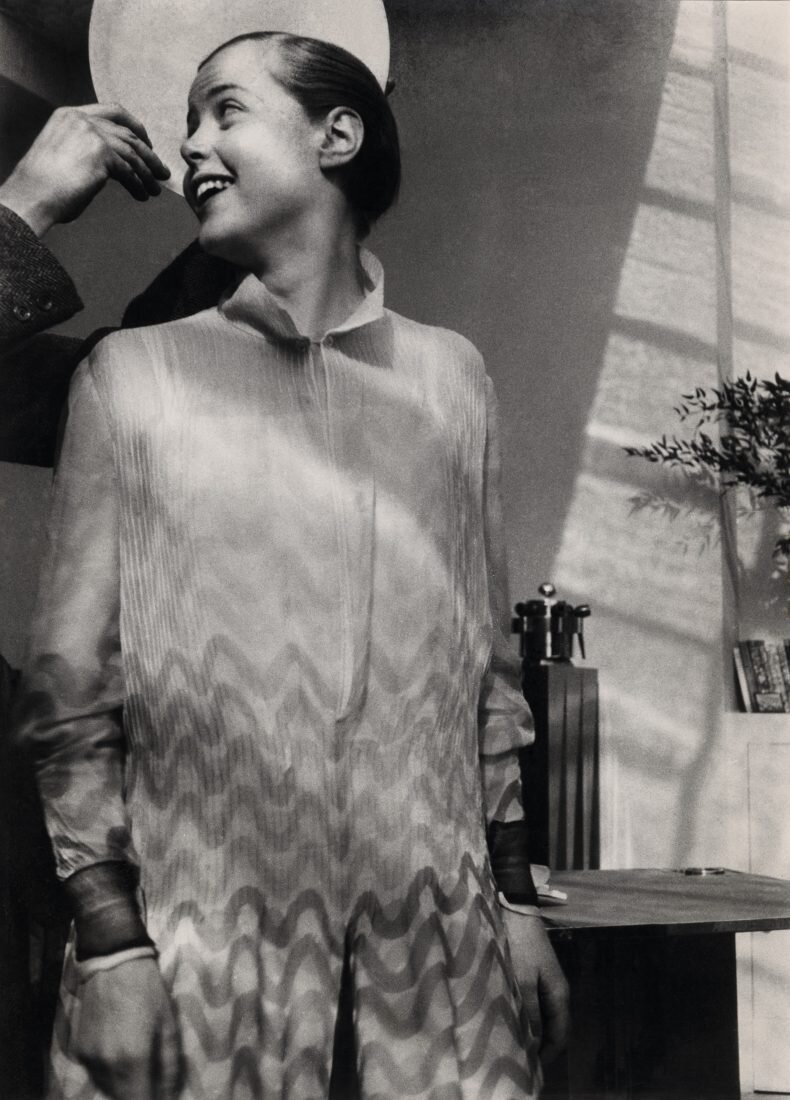

‘Sophie Taeuber with her Dada head’, 1920, by Nicolai Aluf (Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin)

I recently attended a fine exhibition of the work of Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp (Tate Modern, London until October 2021).

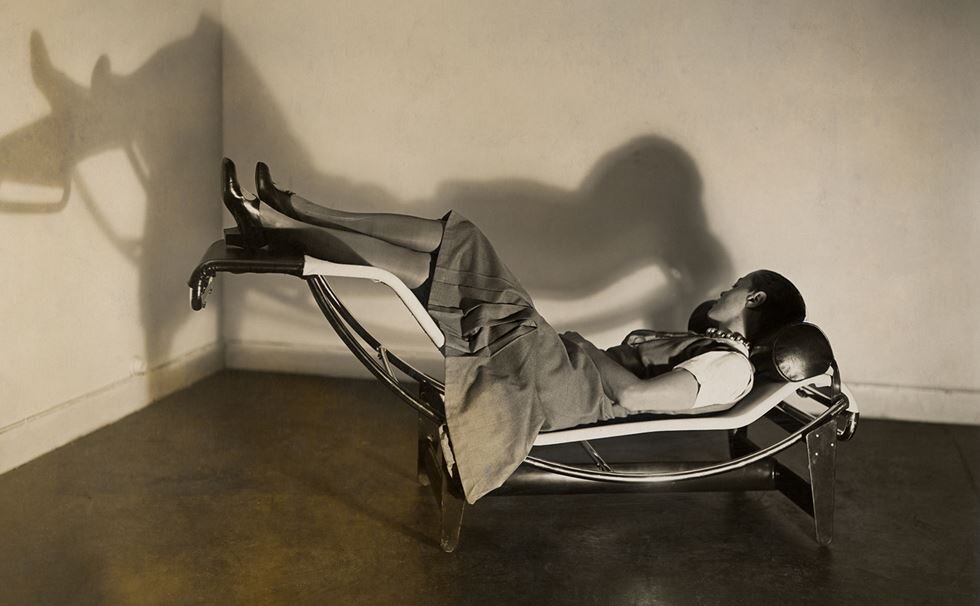

Taeuber-Arp applied her creativity across a range of media: from cushions, bags and necklaces; to stained glass, furniture, rugs and tapestries. She painted and danced; taught and edited; designed costumes, stage-sets and marionettes. She defied all categorisation, denied every traditional hierarchy. She broke down walls.

Sophie Taeuber was born in Davos in 1889. Her father, a pharmacist, died of tuberculosis when she was still a child. Having studied drawing in Switzerland, she moved to Germany to take classes in design, woodwork, weaving and beadwork. From the outset she was interested in developing a diverse set of skills.

‘For some weeks I’ve been really torn, as I still don’t know which kind of workshop I should join. I think textile design suits me, and it’s relatively easy to find something to do with it, too.’

At the outbreak of the First World War Taeuber returned to Zurich where she studied modern dance with the choreographer Rudolf von Laban, taught textile design at the School of Arts and Crafts, and embarked on a career in the applied arts.

Taeuber’s work was rooted in simple colour-block patterns that she created as watercolours, exploring the infinite possibilities of shape, shade and juxtaposition. Sometimes she introduced suggestions of figures that danced joyously off the page. She applied these designs to patterned purses, beaded necklaces and embroidered pillowcases; to fashion, furnishings and furniture.

‘I ended up doing a whole series of little watercolours, which I can easily rework for beaded bags, cushions, rugs and wall fabrics.’

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Purse / Perlbeutel, 1917-1918. Silk, glass beads, knitted. Switzerland. Via Museum für Gestaltung Zürich

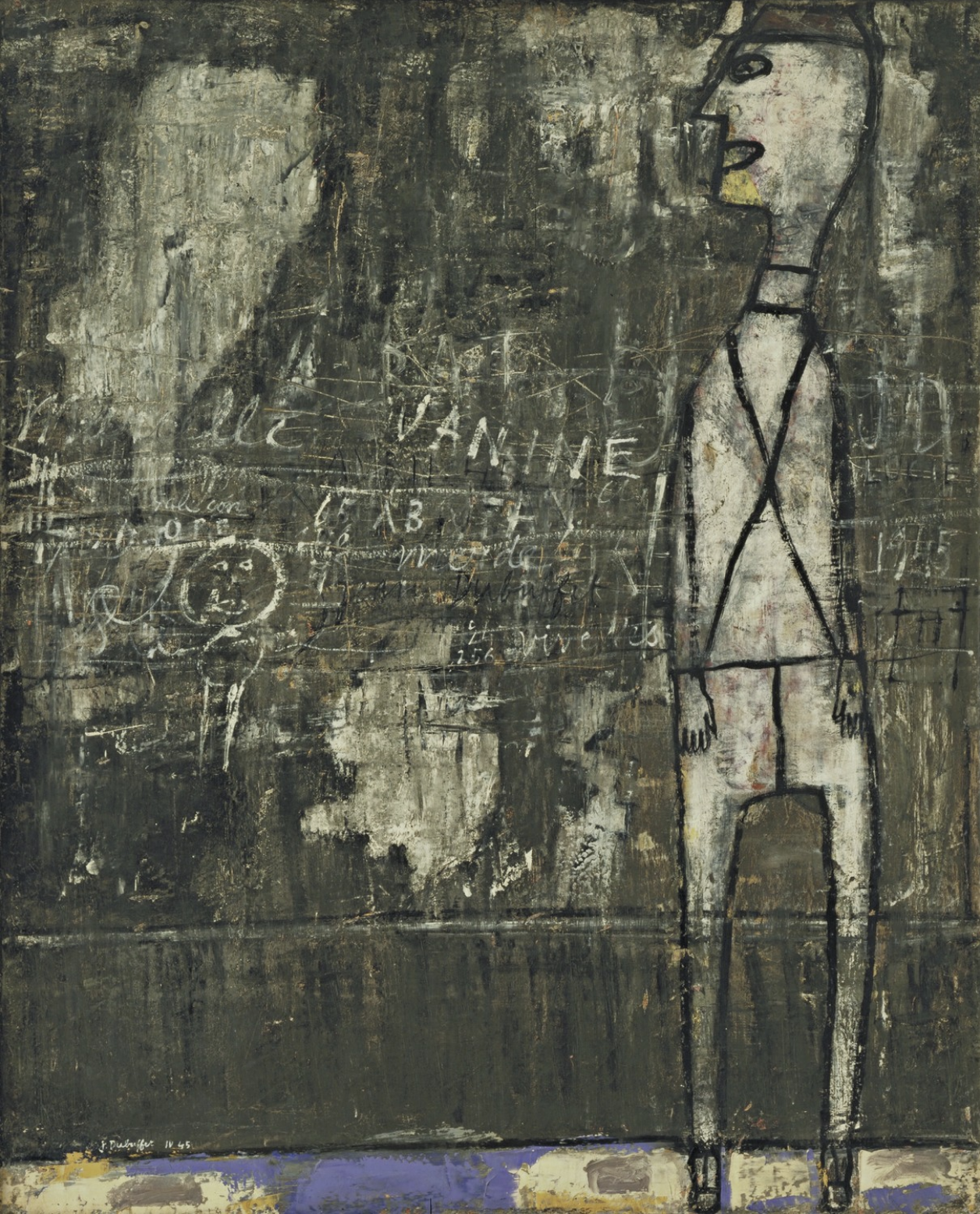

Many artists fled to neutral Switzerland to escape the War, and Taeuber became active in the Dada movement that flourished in Zurich as a result. This group of painters, poets and performers rejected the logic, reason, and conventions that had led to the conflict. Instead they embraced nonsense, irrationality and the absurd.

Taeuber designed costumes, sets and puppets for Dada performances. She danced in avant-garde shows at the Cabaret Voltaire - in masks and under false names, so as not to upset her bosses at the School of Arts and Crafts.

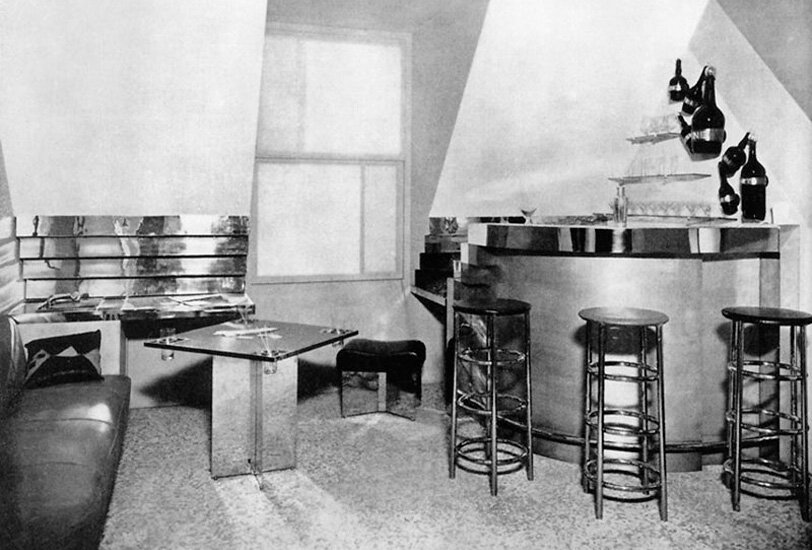

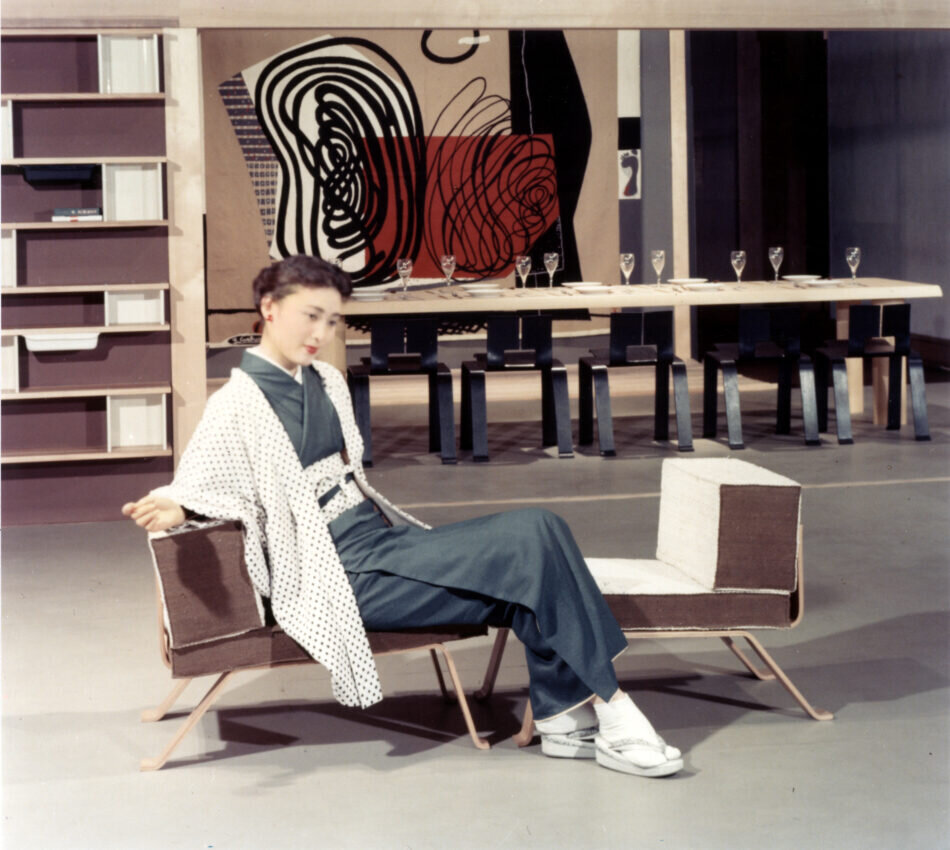

Taeuber particularly enjoyed collaborating with French artist Hans Arp and they became partners. After the War the couple travelled extensively and worked on architecture and interior design projects for cafes, hotels and private homes. They married in 1922, took on French citizenship and settled near Paris.

In the 1930s Taeuber-Arp joined various Paris-based artist groups, she founded a journal and continued to teach. In her work she persisted in exploring the relationship between line, form and colour, in pictures and wooden reliefs. Her geometric abstractions were cool, considered and playful. Bright hued curves, cones and contours skipped across the canvas. Sharp triangles, sinuous lines and jaunty circles jostled for attention.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp ‘Angela' (marionette for King Stag) 1918 Museun für Gestaltung, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Zurich. Decorative Arts Collection

In 1940, when German troops invaded Paris, Taeuber-Arp and her husband fled to southern France and in 1942 they returned to Zurich.

And then one night in January 1943, Taeuber-Arp missed the last tram home and slept in a snow-covered summer-house. She was found the next day, dead from the carbon monoxide that had issued from a faulty stove. She was 53.

Despite her tragic end, Taeuber-Arp left an enduring impression of joyfulness and love of life. Her work was vibrant, colourful, inspiring. And in photos she always seemed to be smiling, laughing, exuberant. In a 1937 letter to her goddaughter she wrote:

'I think I have spoken enough to you about serious things; which is why I speak [now] of something to which I attribute great value, still too little appreciated — gaiety. It is gaiety, basically, that allows us to have no fear before the problems of life and to find a natural solution to them.’

Animated Circles 1934 by Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1934)

We could all learn a great deal from Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Within the creative industries you’ll still find segmented disciplines; hierarchical attitudes towards different platforms and between creativity and craft. Taeuber-Arp encourages us to work freely, without restraint, across categories; to break down those walls; to distill our delight with the world and share it.

'The intrinsic decorative urge should not be eradicated. It is one of humankind's deep-rooted, primordial urges. Primitive people decorated their implements and cult objects with a desire to beautify and enhance.’

'Breakin' down the walls of heartache, baby.

I'm a carpenter of love and affection.

Breaking down the walls of heartache, baby.

I got to tear down all the loneliness and tears

And build you up a house of love.’

The Bandwagon, 'Breakin' Down The Walls Of Heartache’ (D Randell / S Linzer)

No. 335