Dubuffet: Waging a War Against Cultural Conditioning

Jean Dubuffet - 'Landscape with Argus' 1955

‘Millions of possibilities of expression exist outside the accepted cultural avenues.’

Jean Dubuffet

I recently visited an excellent exhibition of the work of French painter Jean Dubuffet. (‘Brutal Beauty’ is at the Barbican, London until 22 August.)

Dubuffet was a singularly independent thinker. He rebelled against established artistic norms. He celebrated art created by people not considered artists. He worked with materials, processes and concepts that expanded our understanding of what art could be. He created new worlds of beauty and meaning. He was an outsider.

'Without bread we die of hunger, but without art we die of boredom.’

Let us consider what Dubuffet teaches us about the creative mindset.

1. Reject ‘Cultural Conditioning’

Dubuffet was born in Le Havre in 1901 to a family of wine merchants. In 1918 he moved to Paris to study painting at the Académie Julian. After just six months he packed it all in, finding the formal training too restrictive and conservative.

Henceforth Dubuffet spent a lifetime kicking against what he regarded as ‘cultural conditioning.’

'Our culture is like a garment that does not fit us, or in any case no longer fits us. This culture is like a dead language that no longer has anything in common with the language of the street. It is increasingly alien to our lives.’

Dubuffet travelled to Italy and Brazil, pursued his own studies in music, poetry, and languages. And when he returned to France in 1925, he established himself as a vintner in Paris. Over the next twenty years, he rarely picked up a paintbrush.

2. Seek Creativity ‘in its Pure and Elementary State’

Since the 1920s Dubuffet had been interested in art created by psychiatric patients, prisoners and children. He admired the honesty, directness and vitality that he saw in such work, and applauded the fact that it didn’t adhere to any tradition or movement. He coined the term Art Brut (‘raw art’) for work produced by non-professionals outside aesthetic norms. And in 1948 he co-founded the Compagnie de l’Art Brut, which collected more than 1,200 pieces by over 100 artists for its ‘museum without walls.’

Art Brut embraced a diverse set of styles and themes. At the Barbican exhibition you can see Madge Gill’s elegant pen and ink designs of fashionable women; Auguste Forestier’s characterful carved wooden beast; and Laura Pigeon’s mournful blue abstracts. There are dense graphic patterns, architectural constructions, psychedelic creatures and a collage map of France.

‘It is my belief that only in this Art Brut can we find the natural and normal processes of artistic creation in their pure and elementary state.’

3. ‘Plug into the Present’

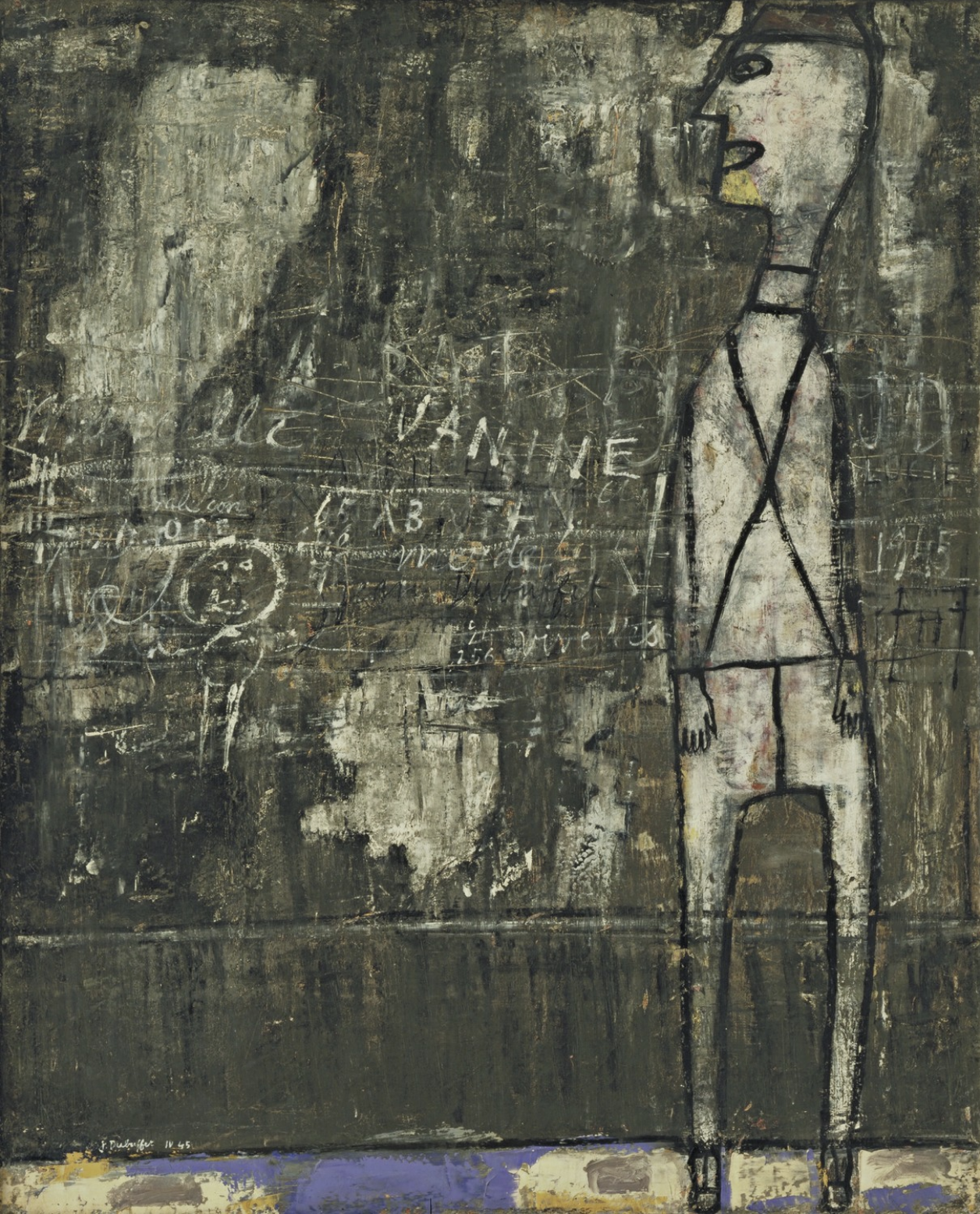

Inspired by the sights of war-ravaged Paris, Dubuffet took up painting again in 1942. He made lithographic prints that looked like defaced walls. Over formal text from French and German newspapers, he scrawled graffiti suggestive of secret Resistance messages.

‘The key is under the shutter.’

‘I’ve been thinking of you.’

Dubuffet was determined that his art should respond to the real world, not to any artistic fashion or convention.

‘I aim for an art that is directly plugged into our current life.’

Jean Dubuffet - Wall with Inscriptions, April 1945

4. Embrace the Editorial Power of Memory

In the late ‘40s Dubuffet developed his own primitive style of portraiture. Having spent hours staring at a sitter, he withdrew to his studio and painted entirely from recollection, creating what he called ‘a likeness burst in memory’. His work was cartoonish, childlike and raw, focusing on a few distinguishing features, rather than seeking to capture a detailed resemblance.

'In portraits you need a lot of general, very little of specific.’

5. Employ Unorthodox Materials

Dubuffet liked to work with unconventional materials. He mixed thick oil paint with sand and cement, pebbles and plaster, string and straw, glass and gravel. He applied razor blades and sandpaper to the paste, scratching and slashing it to give it texture.

'Mud, rubbish and dirt are man's companions all his life. Shouldn't they be precious to him, and isn't one doing man's service to remind him of their beauty?'

Dubuffet also experimented with ‘assemblage’, creating collages with found materials; with butterfly wings or remnants of previous paintings. He made figures from steel wool, charcoal, vines and lava stone; from the debris of a burnt-out car.

'Art should be born from the materials.’

6. Explore the Landscape of the Mind

Between 1947 and 1949 Dubuffet travelled to Algeria for inspiration. He learned Arabic and lived with Bedouin communities in the desert. On his return to Paris, with the aid of his sketchbooks, he sought to capture the spirit of the places he had visited.

'Art addresses itself to the mind, and not to the eyes.’

Dubuffet’s landscapes were brimful of mysterious patterns, shapes and contours, the horizon relegated to a thin distant strip at the top of the canvas. He believed that these paintings could articulate interior as well as exterior truths.

‘I have been concerned to represent, not the objective world, but what it becomes in our thoughts.’

Jean Dubuffet - ‘Landscape in Metamorphosis’

7. Think Micro Macro

In 1957, prompted by his time in Vence, Dubuffet embarked on his ‘Texturology’ paintings. He adopted a technique used by Tyrolean stonemasons, which involved shaking a branch loaded with paint over fresh plaster in order to soften its colour. The tiny spattered dots in subtle shades of cream, brown and grey suggested both the delicate beauty of a microscopic world and the infinite allure of the cosmos.

‘Teeming matter, alive and sparkling, could represent a piece of ground … but also evoke all kinds of indeterminate texture, and even galaxies and nebulae.’

Jean Dubuffet - 'The Exemplary Life of the Soil (Texturology LXIII)’, 1958

8. 'Start All Over Again from the Beginning’

In 1961 Dubuffet returned to Paris and realised that he needed a fresh start.

‘I live locked up in my studio doing - guess what? - paintings in the spirit and manner of those I was making in 1943. I have decided to start all over again from the beginning.’

Dubuffet set about capturing the vibrant spirit of what he called the ‘Paris Circus’: the posters, traffic, restaurants and bars – an urban realm of chaotic, colourful energy.

‘I want my street to be crazy, my broad avenues, shops and buildings to join in a crazy dance.’

9. Find Inspiration in the Unconscious

In 1963 Dubuffet was inspired to take another new direction by some doodles he made during a telephone call. In his ‘L’Hourloupe’ series he created his own highly stylized graphic world of fluid shapes, coloured in with blue and red stripes; of twisting and turning jigsaw figures, full of vim and vigour.

'It is the unreal that enchants me now.’

Next Dubuffet breathed life into this doodle-universe by inventing a one-hour spectacle, ‘Coucou Bazar.’ He choreographed ‘theatrical props’ - some static, some powered by motors - with live dancers, dramatic lighting and a musical accompaniment - which he stipulated should be ‘brutally loud with abrupt interruptions of silence.’

Jean Dubuffet - ’Skedaddle'

10. Let the Imagination Bleed into the Everyday

’The things we dearly love, which form the basis of our being, we generally never look at.'

In the late ‘70s Dubuffet returned to assemblage. For his ‘Theatres of Memory’ series he created enormous collages with layered fragments of old paintings. Crude cartoon characters jostle with bold abstract shapes and colours. Trees and masks are enmeshed with fierce monochrome patterns.

When they were exhibited in New York in 1979, these works inspired a new generation of artists, including Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Dubuffet said he was concerned with how our imagination bleeds into our impressions of the everyday world.

'What interests me about thought is not the moment when it crystallises into formal ideas, but its earlier stages.’

Dubuffet died from emphysema in 1985. He was 83. He had endeavoured to return art to untutored primitivism. Constantly reinventing his process and style, he sought relentlessly to explore interior and exterior truths; to blur the boundaries between the psychological and the real, the micro and the macro. And in so doing he created magical worlds of beauty and vitality.

'For me, insanity is super sanity. The normal is psychotic. Normal means lack of imagination, lack of creativity.’

Above all, Dubuffet raged against tradition and taste, custom and convention: what others decree as ‘normal’. Creativity should not follow any prescribed path or respect any established practice. It should be an unshackled expression of self.

’There is only one way of being normal, and a hundred million ways of not being normal.’

'Express yourself.

Express yourself.

You don't ever need help from nobody else.

All you got to do now,

Express yourself.

Whatever you do,

Do it good.

Whatever you do, do, do,

Do it good, all right.

It's not what you look like

When you're doin', what you're doin’.

It's what you're doin', when you're doin'

What you look like you're doin’.

Express yourself.

Express yourself.’

Charles Wright and the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band, 'Express Yourself’ (C Wright)

No. 326