The South Indies: When Over Thinkers Under Perform

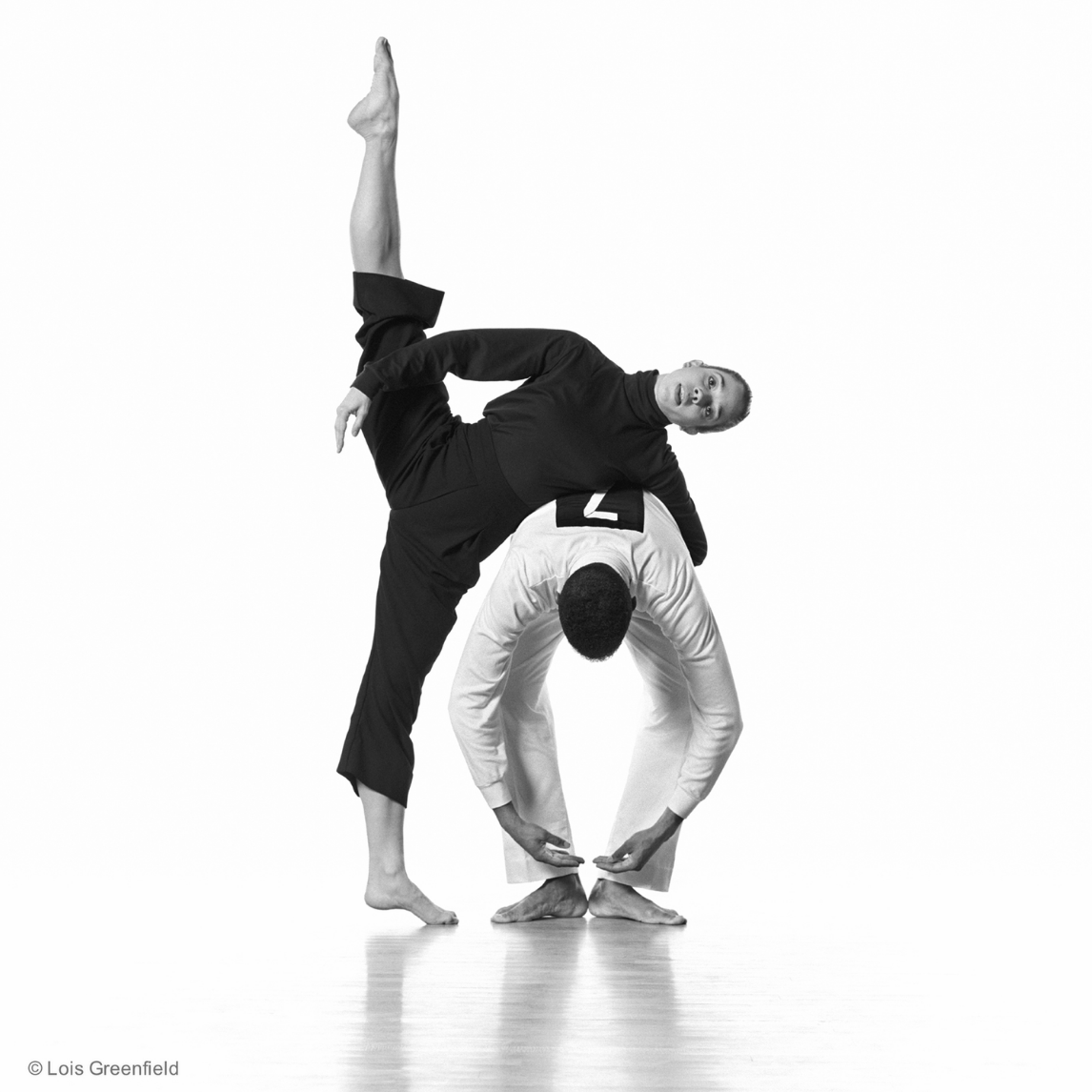

Moore’s tackle on Jairzinho

‘Football is the most important of the less important things in the world.‘

Carlo Ancelotti

I think the South Indies football team mattered more to me than it really should have.

Through the week I washed the kit, recruited players and popped out to Soccer Scene to buy random bits of equipment. I woke up in the middle of the night pondering league tables. I plotted innovative formations on the back of envelopes, but ended up concluding that, erm, 4-4-2 probably best suited our resources.

We were in many ways a typical amateur side. Our fixtures tended to be on Saturday mornings when many of our personnel were nursing hangovers. Our home ground was the astroturf at Market Road - where Australians sold their VW Camper Vans and local kids hung round to nick our balls.

Like most such squads, we were a mismatched assortment of characters and talents. John did warm-up exercises that the rest of us scorned for being too ‘continental.’ Dylan was a philosopher off the pitch and an enforcer on it. Tim played with the enthusiasm of a 20 year old, though his body had moved on a decade or so. Andy was quiet, but lethal. Matty kept goal, but not his temper. Striker Kweku had the disarming habit of chatting amicably to opposition Defenders. Vinny played like a troubadour social worker and Tony like a novelist with a fine appreciation of history. Thommo was stylish. Caz was obdurate. Dave was rustic. Doug was contrary. Steve was tidy. And Shamik was late.

‘If I have to make a tackle then I have already made a mistake.’

Paolo Maldini

My own skills as a Centre Back were rudimentary. Slow, lumbering, physical. More comfortable with the ball in the air than on the ground. Whenever a Striker approached me in possession, I could hear over my shoulder Thommo shouting:

‘Stand up. Stand up, Jim!’

I hesitated and held my ground. I stared the Striker in the face as he contemplated his next move.

‘Don’t dive in!’ Thommo cried.

For a brief moment the Striker and I were frozen to the spot, each ready to spring into action. Time stood still.

I felt the same way about this bloke as I did about all Forwards. I resented his speed and agility, his refined skills and youthful good looks. He needed to be taught a lesson. Perhaps, re-enacting Bobby Moore’s tackle on Jairzinho in the 1970 World Cup, I could slide in to dispossess him, with balletic grace, with pinpoint precision.

And then, suddenly, he feinted as if to go one way and went the other. I sensed him accelerate past me as I struggled to build up momentum.

It was now or never.

And so, with a rush of blood to the head, I made my move.

Thud, clatter, crash.

I’d taken him down.

Penalty.

I looked up from the astroturf to see Thommo frowning at me with accustomed disappointment.

'Football is a game you play with your mind.’

Johan Cruyff

A little while ago I read an article about the science of spot kicks (‘Want That Penalty?’ The Times, 7 May).

It transpires that, if you’re taking a penalty to win a match, you can expect a 90% success rate, compared with only 60% if you’re trying to avoid defeat. In a shoot-out, striking the first penalty elevates your chances of winning to 60:40. Keepers should waste between 1.7 and 4.5 seconds before the kick is taken.

There’s clearly a good deal of psychology involved.

A recent study published in the journal ‘Frontiers in Computer Science’ monitored the brains of footballers when they took spot kicks.

22 players were fitted with a cap with sensors that measured oxygen levels in different parts of the brain. Those who missed their penalty tended to have activated cerebral areas associated with long-term planning. By contrast, those who scored had employed unconscious neural pathways. They had performed the task automatically, with well-rehearsed movements.

The research concluded that players miss penalties when they over-analyse the outcomes. Over thinkers under perform. They would do better to employ ‘neural efficiency theory,’ responding to pressure by switching some parts of the brain on and others off.

’The best decisions aren’t made with your mind, but with your instinct. The more familiar with a situation you become, the quicker, the better your decision will be.’

Lionel Messi

It’s easy to imagine such findings having application in business.

Inevitably we spend a good deal of the working week plotting and planning, calculating and co-ordinating. We repeatedly rehearse our arguments, review the pros and cons of various strategic routes, in order to equip ourselves to make the critical calls. But as we approach the key meeting, we should not be too preoccupied with the consequences of our actions. We should be confident, focused on winning, set to seize the initiative. At the decisive juncture in the negotiation; at the point of making the crucial creative recommendation; at the climax of the presentation, we should switch from a mindset of preparation and projection to one of instinct and intuition. We should concentrate on the situation and not the stakes.

After the game we’d adjourn to the Hemingford Arms. Caz, in his genial way would talk to the opposition at the bar and smooth over grievances and misperceptions. The rest of us would sit in a huddle in the corner, re-enacting the highlights, exaggerating our heroics, appointing the scapegoat - usually me.

'My heart was broken.

Sorrow, sorrow.

My heart was broken.

You saw it, you claimed it,

You touched it, you saved it.

My tears are drying.

Thank you, thank you.

My tears are drying.

Your beauty and kindness

Made tears clear my blindness.

While I'm worth

My room on this Earth,

I will be with you,

While the Chief

Puts sunshine on Leith.’

The Proclaimers, 'Sunshine on Leith’ (C & C Reid)

No. 325