Charlotte Perriand: ‘The Art of Living’

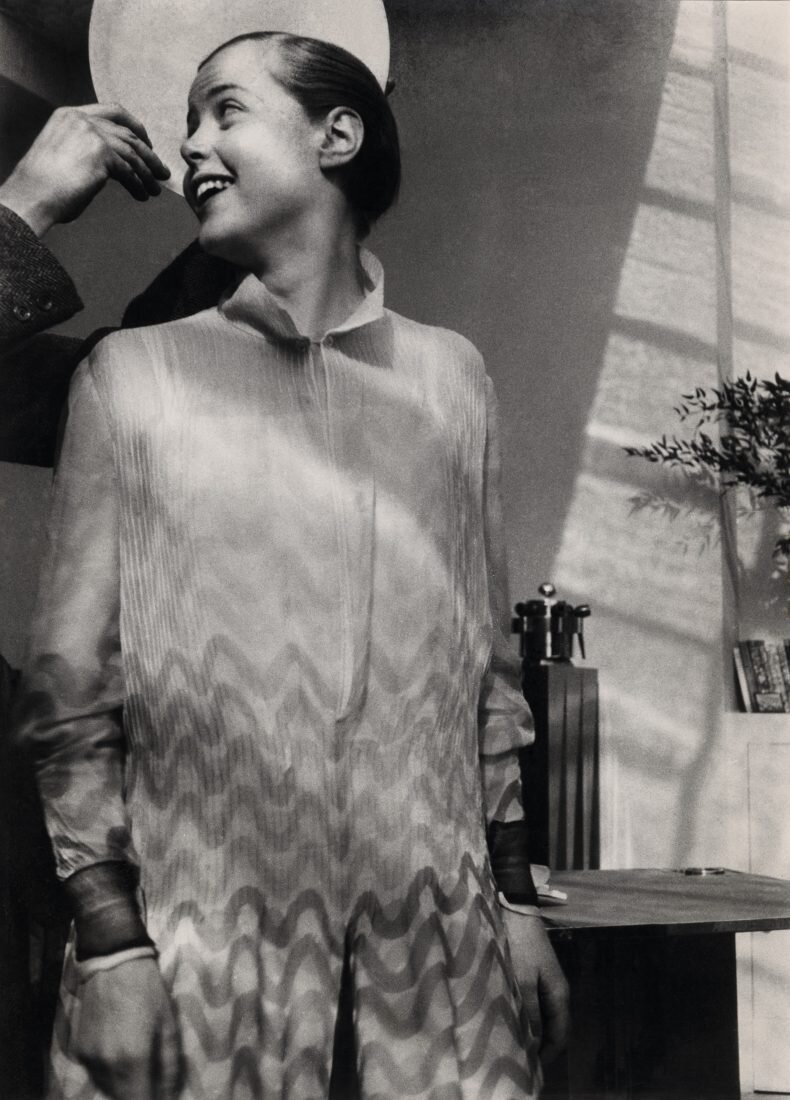

Charlotte Perriand in her studio on place Saint-Sulpice, Paris, 1928. The hands holding a plate halolike behind her head are Le Corbusier’s. Photo: Archives Charlotte Perriand

'The extension of the art of dwelling is the art of living.’

Charlotte Perriand

I recently visited an excellent exhibition of the work of designer Charlotte Perriand (The Design Museum, London until 5 September).

Perriand applied modernist principles to furniture design. She didn’t decorate a room, she equipped it for living. Her furniture addressed fundamental human needs and desires. Her interiors embraced space, light and flexibility. And she recognised the huge importance of storage. Critically, with experience she evolved her approach: she learned from her travels; she synthesised traditional craftsmanship with industrial production. She responded to ‘transient times.’

'Dwellings should be designed not only to satisfy material specifications; they should also create conditions that foster harmonious balance and spiritual freedom in people’s lives.'

Here are some lessons derived from Perriand’s full and fascinating life.

1. Better Design Creates a Better Society

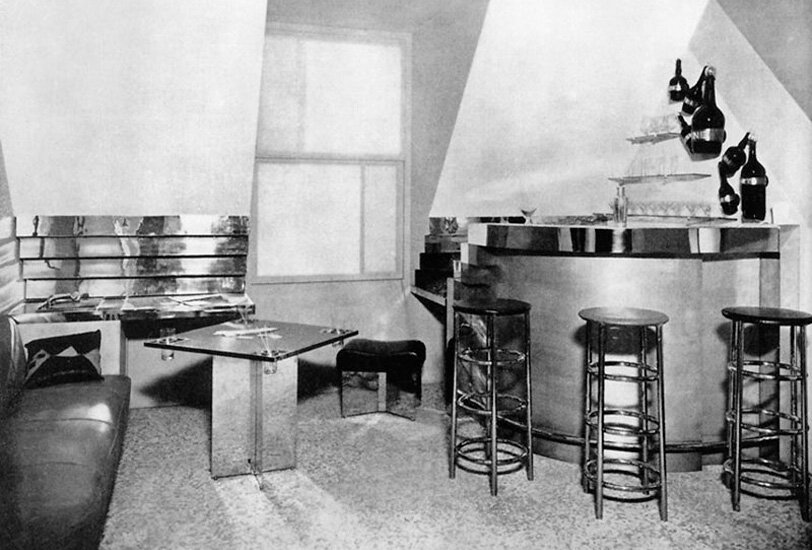

Born in Paris in 1903 to a tailor and a seamstress, Perriand studied furniture design at the École de L'Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. Two years after graduating, she renovated her loft apartment, turning it into a compact modernist dream. Her Bar sous le Toit (‘Bar under the roof’) had a built-in cocktail-bar of aluminium and glass, with nickel-plated copper stools; a chrome-plated table with a fitted gramophone; a leather banquette.

In 1927 Perriand applied to work at the studio of modernist architect Le Corbusier. She was rudely rejected.

‘We don't embroider cushions here.’

A month later however, Le Corbusier saw a recreation of Perriand’s Bar sous le Toit at an exhibition, and promptly offered her a job in furniture design.

Bar sous le Toit (‘Bar under the roof’)

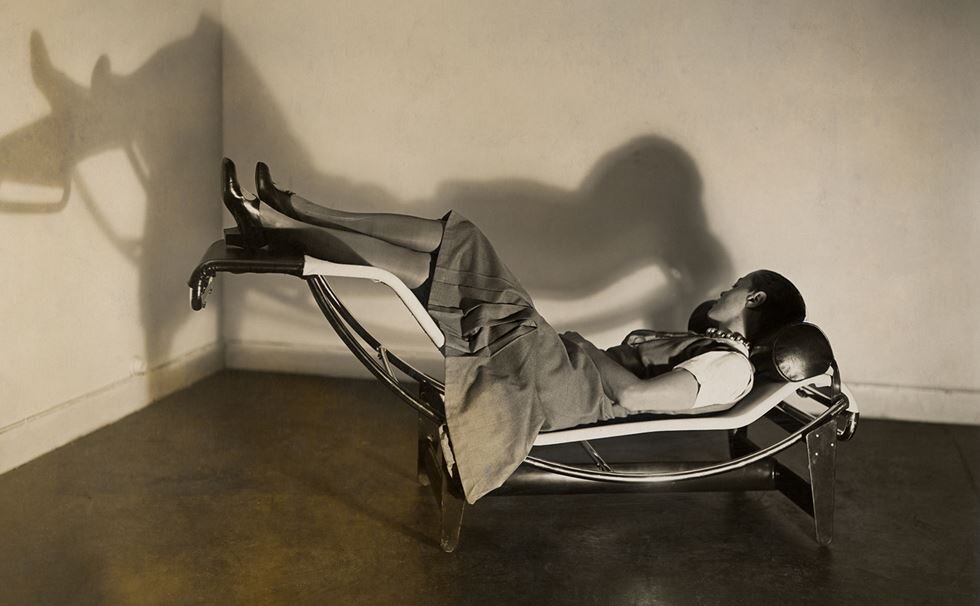

Working alongside Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, Perriand designed three chairs for three different tasks - all employing highly functional tubular steel: the Fauteuil au dos basculant, a light chair with canvas back and seat, ideal for conversation; the Fauteuil grand confort, an easy chair with square leather cushions, for relaxation; and the Chaise longue, a futurist machine for sleeping. They all became classics.

Perriand imagined that her tubular steel furniture could be mass-produced by Peugeot, the bike manufacturer. They didn’t quite share her vision.

'Our attempts at talks with the Peugeot bicycle company resulted in half an hour of total incomprehension.'

Perriand believed that better design helped create a better society. She worked with modern materials in bold colours; experimented with movable, foldable functionality; valued space, fresh air and light.

‘Hygiene must be considered first: soap and water.

Tidyness: standard cupboards with partitions for these.

Rest: resting machines for ease and pleasant repose.’

The Studio, 1929

There are a number of photographs of Perriand around this time. She sports a close-cropped bob, wears a dress with a bold print and a self-made necklace of industrial ball-bearings. She looks confident, playful, thoroughly contemporary.

2. ‘Adapt to Transient Times’

'Everything changes so quickly, and what is state-of-the-art one moment won’t be the next. Adaptation has to be ongoing – we have to know and accept this. These are transient times.'

In the 1930s Perriand was heavily involved with left-wing politics. To this end she designed a dwelling for low-income families for which each individual was allocated 14 square metres. And as the modernist machine aesthetic became increasingly associated with militarism - cold and inhumane - so she set aside expensive chrome. Instead she embraced natural forms and handcrafted techniques; affordable materials that could be mass produced and easily constructed.

On weekend expeditions with friends to the Normandy beaches Perriand took inspiration from found objects.

'We would fill our backpacks with treasures: pebbles, bits of shoes, lumps of wood riddled with holes, horsehair brushes—all smoothed and ennobled by the sea.’

Perriand on the chaise longue

3. ‘Choose Life’

At the exhibition you can see Perriand’s notebooks and plans. She began designing her chairs by reviewing current models and then she explored what was possible from first principles. Her sketched ideas were detailed, vibrant and thoughtful. When she worked on a building, she spent time visiting the site alone, absorbing its natural qualities.

'In every important decision there is one option that represents life, and that is what you must choose...Life is something in motion.’

4. ‘Better to Spend a Day in the Sun than to Spend it Dusting our Useless Objects’

Le Corbusier had not given Perriand due credit for her designs and, after working with him for a decade, she ‘stepped out of his shadow.’

In 1940 she travelled to Japan (before it entered the War) as an official advisor for industrial design. She fell in love with the country’s open, flexible interiors; with their simplicity, harmony and emptiness.

As a result, Perriand developed a fascination with storage. She determined that an ordered environment decreased anxiety and increased quality of life.

'What is the crucial element in domestic equipment? We can answer that immediately: storage. Without well-planned storage, it is impossible to find space in one’s home.’

And so Perriand set about designing affordable storage systems with simple plastic drawers; modular shelving that liberated space.

‘Better to spend a day in the sun than to spend it dusting our useless objects.’

Perriand worked on many projects after the War: corporate offices, mountain shelters and student housing. In 1951, having patched up her differences with Le Corbusier, she created the interiors and kitchens for the famous Unité d'habitation. She designed the League of Nations building in Geneva, the remodelling of Air France's offices in London, Paris and Tokyo.

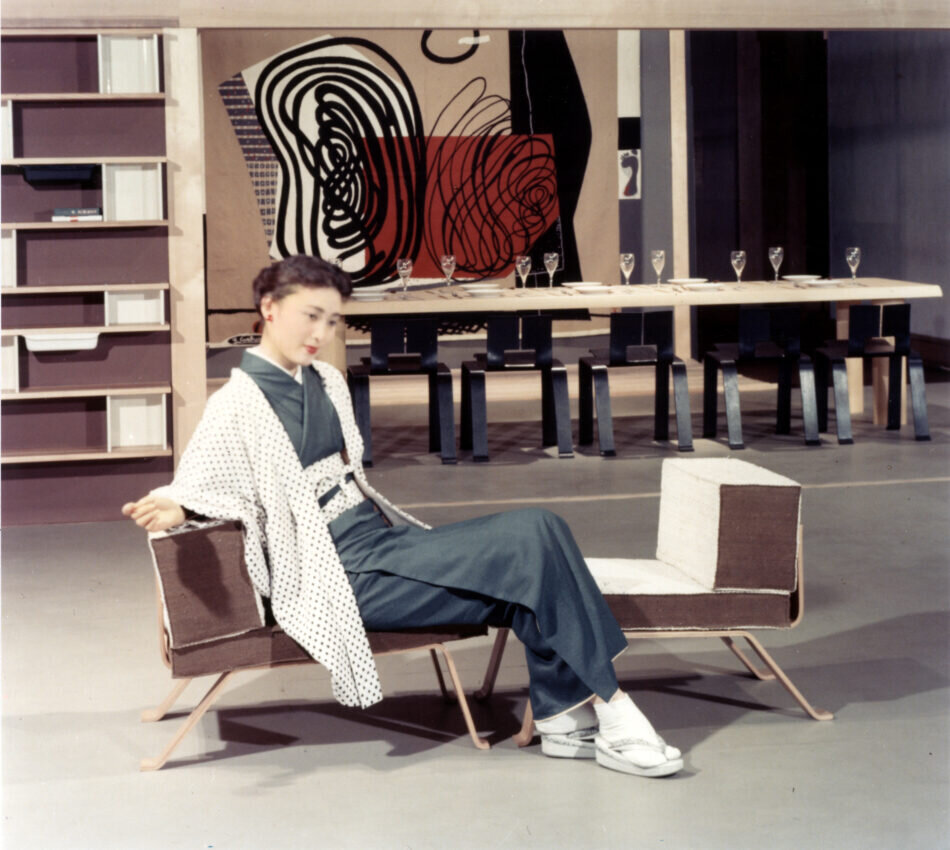

Proposition d'une synthèse des arts, Takashimaya department store, Tokyo, 1955

5. ‘Keep Morally and Physically Fit’

Perriand was an outdoor enthusiast, and she had a special interest in ski resorts.

‘We must keep morally and physically fit. Bad luck for those who do not.’

At Les Arcs in Savoie she led a group of architects: designing a complex that nestled into the mountain; arranging the apartments in a series of staggered terraces cascading down the hillside; integrating prefabricated bathrooms and kitchens. Since guests would spend most of their time outdoors, the rooms were minimal in scale, but they looked out onto nature.

'I love the mountains deeply. I love them because I need them. They have always been the barometer of my physical and mental equilibrium.’

Perriand died in 1999. She had designed furniture as equipment for the machine age. But her modernism was not cold and clinical. Rather it was people-centred and collaborative; warm and humane. And it changed with the times. She recognised that the West could learn from the East; and that nature had a critical part to play in the future.

'Everything is linked, the body and the mind; mankind and the world; the earth and the sky.’

'Find a well-known hard man and start a fight.

Wear your shell suit on bonfire night.

Fill in a circular hole with a peg that's square.

But just don't sit down 'cause I've moved your chair.’

Arctic Monkeys, ‘Don’t Sit Down ‘Cause I’ve Moved Your Chair’ (A Turner)

No. 332