A Man Having Trouble With An Umbrella: Recognising the Power of Repetition

My grandfather was a retired policeman with a warm heart and authoritative manner. At weekends he would drive Martin and me along the A13 to his old haunts in Barking, Poplar and Limehouse. Hard to believe now, but ‘going for a drive’ was a popular leisure activity in the ‘70s. At traffic lights and junctions, Grandpa would playfully greet other drivers with a ‘Hello, Mary’ or ‘Yes, of course, Dave, you go first.’ He didn’t actually know Mary or Dave, but he was aware it amused us. And every time we went past a triangular sign indicating road works (by means of the silhouette of a labourer planting his shovel in a pile of earth), Grandpa would exclaim: 'There's a man having trouble with an umbrella!'

We loved that joke. To a young boy it was deeply silly, slightly surreal, somehow subversive. And it improved with repetition. As we rolled around in fits of laughter at the back of the Rover, the gag didn't seem trivial at all to us. It seemed important. And I'm pretty sure it was.

Repetition reassures. It creates a sense of familiarity, intimacy, common currency. Consider catchphrases and slogans; jingles, chants and incantations; aphorisms and end lines. These may be regarded as lower forms of expression, but they have an insidious potency. We assume that familiarity breeds contempt. But often the reverse is true: familiarity breeds contentment.

I recently came across a review of The Song Machine, a new book that considers the methods of the modern music industry and today’s high-tech record producers. It’s a calculating world of ‘writer camps’, ‘melodic math’ and the quest for elusive ‘bliss points.’ The author reaches an interesting conclusion about the science of hits:

‘For all the painstaking craft involved… the crucial factor in our emotional engagement with music is familiarity; in other words, if you were repeatedly to hear a song you didn’t like, that proximity would eventually breed affection.’

Mark Ellen/ The Sunday Times, reviewing The Song Machine by John Seabrook

That explains a lot...

Familiarity also resides at the heart of brand value. The first brands were founded on the reassurance of consistency: this product is the same as the last product you bought; it’s made from the same ingredients and it’ll perform in the same way.

I wonder, do we in modern marketing properly appreciate the power of repetition? Of course, we endeavour to be disciplined about visual identity; and, in a media context, we take account of frequency, dwell-time and wear-out. But this is a quantified, rational view of repetition. Do we really understand the qualitative, emotional value of repeated experience?

Earlier this year I attended a production of Aeschylus’ Ancient Greek tragedy, Oresteia. I was particularly struck by this exchange:

‘What’s the difference between a habit and a tradition?’

‘A tradition means something.’

At their best brands are not just mindless habits. Through repeatedly exploring territories and ideas that are relevant to people, the best brands establish their own meaning, their own traditions. In this age of nudge theory and behavioural economics, we spend quite a lot of time seeking to change habits. What would happen if we sought occasionally to establish traditions?

Certainly our creative instincts are all the time working against iteration. They urge us to embrace change, innovation and reinvention at every turn. Every campaign is a fresh challenge; every new brief is a blank sheet of paper. And these instincts are intensified in the modern age. There are infinite platforms to be filled with unique content; there are ever-increasing consumer appetites to be sated. We live in dynamic times of difference and diversity.

In our obsession with reinvention the commercial communication sector is at odds with other creative professions. In the film, gaming and TV industries the occurrence of a hit is a cue to explore sequels, series, formats and box-sets. Why are we so nervous of repeating success?

Of course, none of us needs a return to the dark days when advertising drilled the same messages into the crania of hapless, captive audiences; over and over again. In the interactive age we need communication coherence more than rigid consistency. We need theme and variation, call and response. We need campaigns that evolve and amplify.

It’s sometimes helpful to think of modern brands as ‘meaningful patterns.’ Brands reassure through rhythm and repetition. With infinite variety they examine, echo and expand ideas.

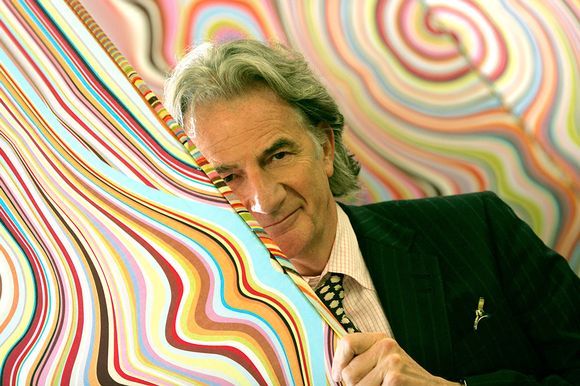

Some years ago I attended a talk by the esteemed fashion designer, Paul Smith. He explained that, when it came to window displays, he believed in ‘the power of the repeated image.’ Accompanying a pale blue cotton shirt with a royal blue version of the same shirt; and then navy and deep indigo; next to a twill or a denim execution of the same design; adding a polka dot pattern, a striped print or floral detail. It was theme and variation played by an orchestra of blue shirts. And it created a very compelling, harmonious effect. At once both thrilling and reassuring.

Perhaps the power of repetition in the digital age is best expressed through the concept of memes. For many marketers memes are merely a form of iterative campaign, something involving white type and cat videos. However, insofar as a meme is ‘an element of a culture or system of behaviour passed from one individual to another by imitation or other non-genetic means’ (OED), then surely brands are memes. Brands exist not in factories or spreadsheets or shop shelves. They exist in people’s minds and in their behaviours. For what is a brand, if not a shared set of behaviours and beliefs? We always sought to create content for brands that was 'talkable'; nowadays we aim to create the imitable, adaptable, copyable and repeatable.

Of course, brand management is fundamentally a balancing act between consistency and change. Some brands are too conservative; others are too capricious. Working out whether to 'stick or twist' is a critical marketing skill. All I'm saying here is that, occasionally, in times of transformation, the argument for holding a steady course gets shouted down.

Perhaps when we’re being seduced by the siren call for radical reinvention, we should also have the tender words of Billy Joel singing in our ears. Repeatedly.

‘Don’t go changing, to try and please me.

You never let me down before.

Don’t imagine you’re too familiar,

And I don’t see you anymore.

I would not leave you in times of trouble

We never could have gone this far

I took the good times, I’ll take the bad times

I’ll take you just the way you are.’

Billy Joel/ Just The Way You Are

No. 57