Biba: ‘The Only Thing You Have Is What’s in Your Head’

I recently attended a fascinating exhibition about the legendary fashion brand Biba. (The Fashion and Textile Museum, London, until 8 September.)

‘The market was instant for that age group, they wanted it there and then. They didn’t want to wait, as they didn’t look to the future in any way.’

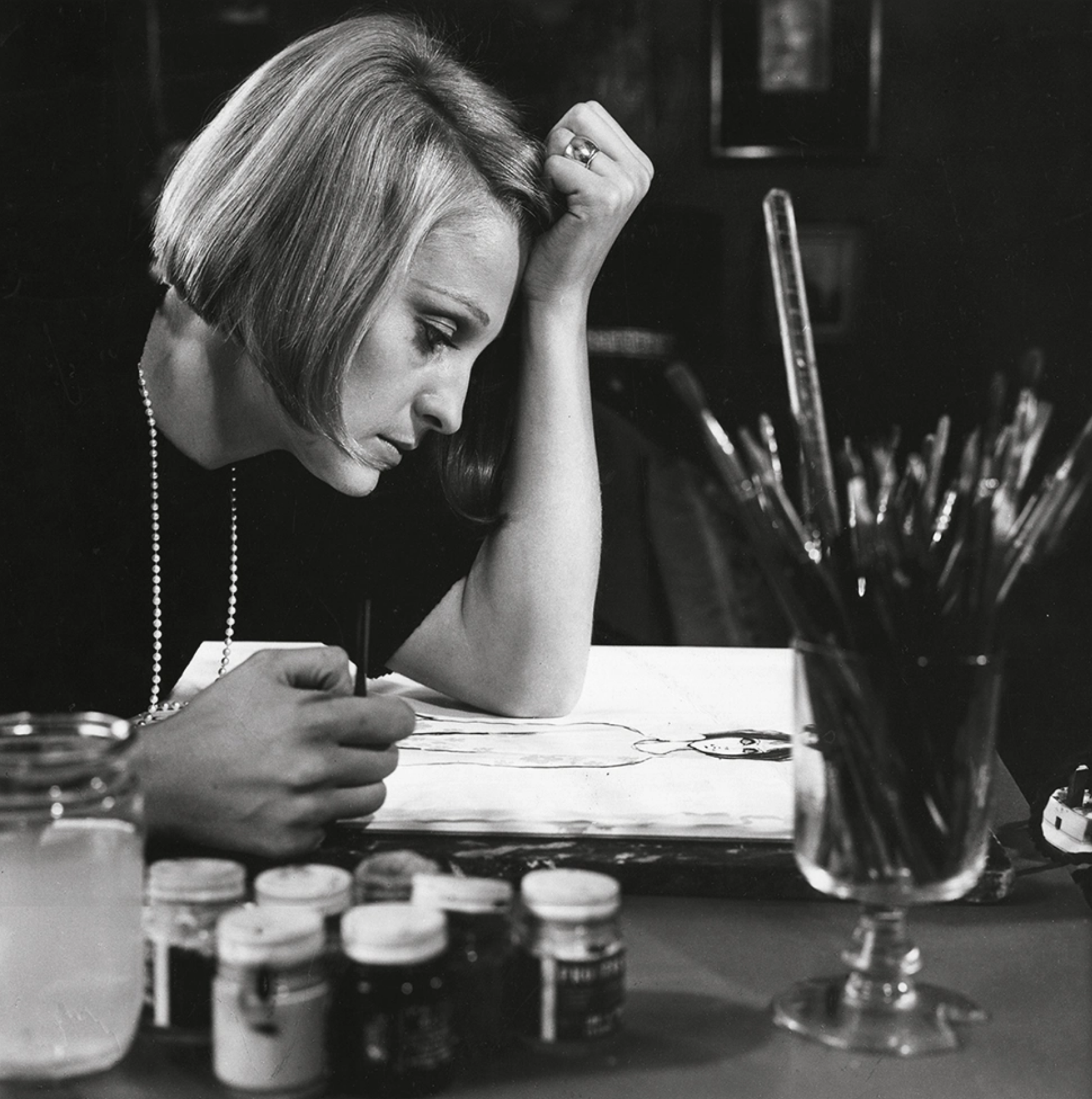

Barbara Hulanicki

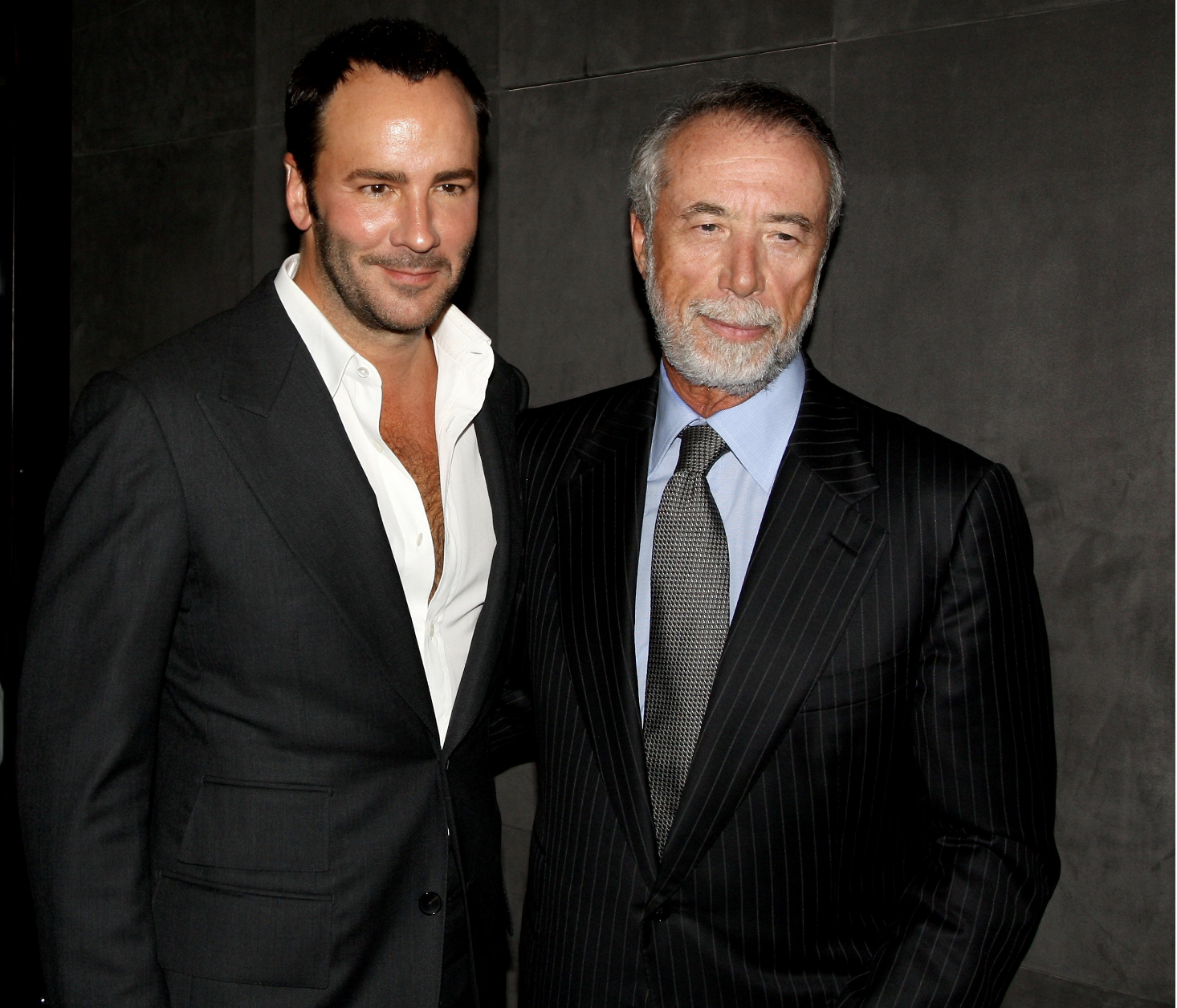

Between 1964 and 1975 Biba sold fast, affordable fashion to young people in London, the UK and beyond. Fusing the creative flair of Barbara Hulanicki with the commercial nous of her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon, Biba offered bold outlines, simple construction, vibrant colours and imaginative fabrics. It was a magical, immersive shopping experience, a lifestyle brand that endlessly reinvented itself.

‘It isn’t just selling dresses, it’s a whole way of life.’

Hulanicki was born in Warsaw in 1936. After her diplomat father was assassinated in Palestine in 1948, the family moved to Brighton. She studied at the Brighton School of Art, and then worked as a freelance fashion illustrator for magazines such as Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Tatler and Women's Wear Daily. She quickly realised that the elite couturiers were out of step with emerging youth culture and the changing tastes of modern women.

Pink Gingham Dress

In 1961 Hulanicki wedded Stephen Fitz-Simon, an ad man employed at the London Press Exchange. With Hulanicki working from home and Fitz-Simon doing long hours in the office, their married life got off to a challenging start.

‘We could both see we were on a collision course, so I was desperate to try and find something we could do together.’

Fitz-Simon foresaw that illustration was being eclipsed by photography, and so encouraged Hulanicki to pursue her interest in design. In 1963 the couple set up a mail order fashion business, Biba's Postal Boutique ('Biba' was the nickname of Hulanicki's younger sister, Biruta). The following year they had their first significant success when they advertised a pink gingham dress and matching headscarf in the Daily Mirror. The outfit looked similar to one recently worn by Brigitte Bardot, and 17,000 units were sold.

Hulanicki and Fitz-Simon were emboldened to open the first Biba boutique, in Abingdon Road, Kensington. The store had a nightclub feel, with dark interiors and loud music, muddled merchandise and clothes hanging from hat-stands. Breaking with the conventions of the time, it offered late-night shopping, young, approachable staff and communal changing rooms.

'It was like fishing: you would never know what you might come back with.’

As a fashion illustrator, Hulanicki was predisposed to simple lines and bold silhouettes, and she avoided fussy details. She designed mini-shift dresses and mini-skirts; jump suits, coats and hats, in ‘bruised’ purple, plum, olive, rust, mulberry, mauve and black - what she called ‘auntie colours.’

‘We started off with just really simple shapes, little smocks and shifts, as it kept the manufacturing headaches away.’

Fitz-Simon aimed to keep prices below the disposable weekly income of the average London secretary. And so the skirts, tops and accessories sold for a few pounds or less, dresses for under three pounds. And for the first few years, to keep costs down, the garments had no label, and were only available in sizes 8 to 12.

‘I wanted to make clothes for people in the street, and Fitz and I always tried to get prices down, down, down.’

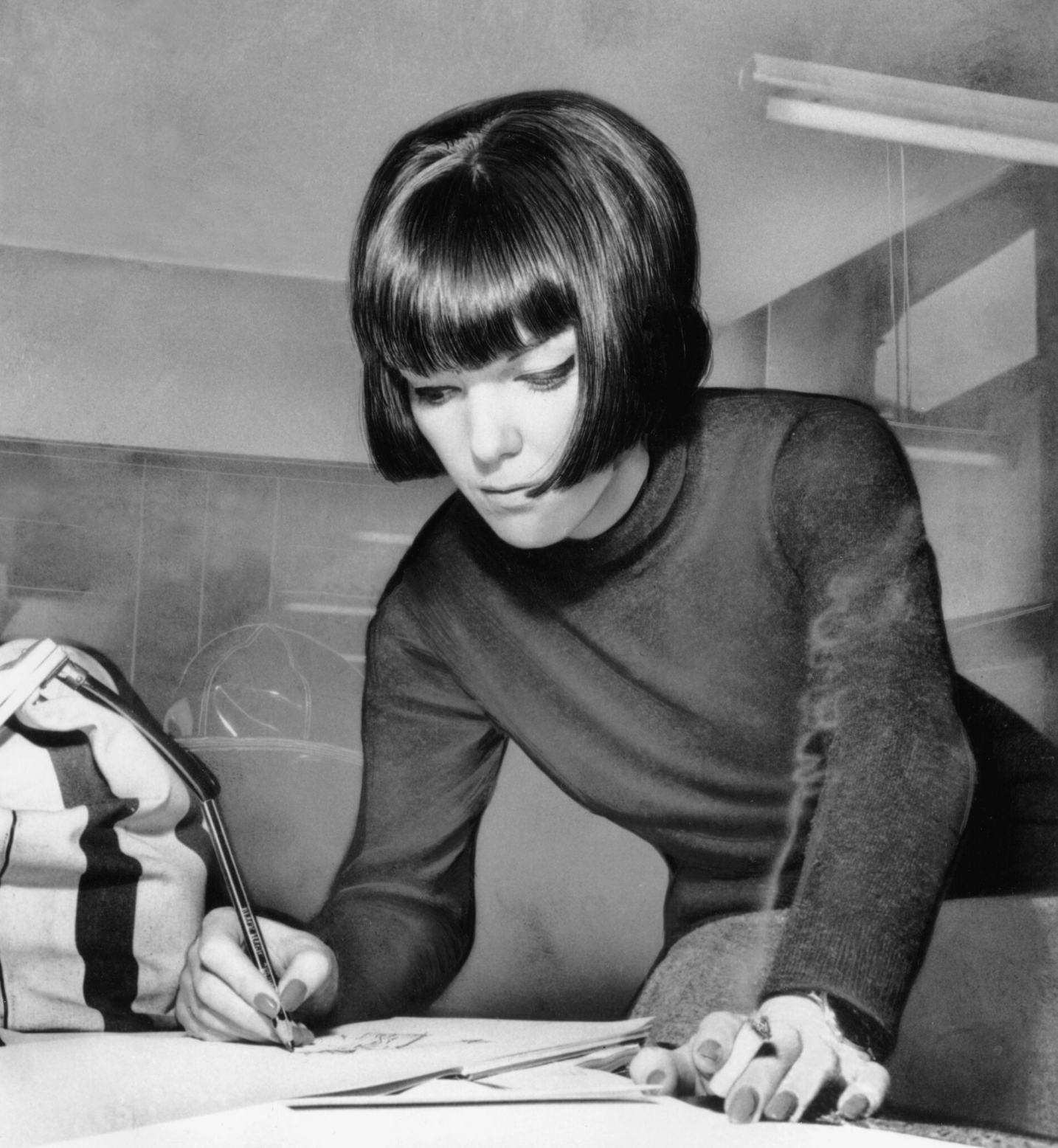

Biba - Bridgeman Images

The Biba boutique became hugely popular, frequented by the glitterati of the day: Twiggy, Cher, Cilla Black and Cathy McGowan. In 1966 they set up in larger premises on Kensington Church Street. The new shop boasted a black and gold exterior, and striking red and gold wallpaper inside, along with antique mahogany shelving.

‘From day one of the first Biba I was never quite certain which came first, the clothes or the interiors.’

In 1969 Hulanicki and Fitz-Simon launched an even bigger Biba store on Kensington High Street, featuring Victorian wooden fixtures and Art Deco inspired sets. Staffed almost entirely by women, the shop had one of the first workplace creches.

As Biba grew, it retained its cost consciousness. Shops opened in autumn and winter months, when sales of coats ensured higher profit margins. Evening dresses were labelled as dressing gowns so that they would be subject to lower tax.

Typically, Hulanicki designed for a young woman with long thin arms, flat chest, low waist and straight hips.

‘The silhouette was as long as possible… like a drawing. [The ideal Biba girl has] a skinny body with long asparagus legs and tiny feet.’

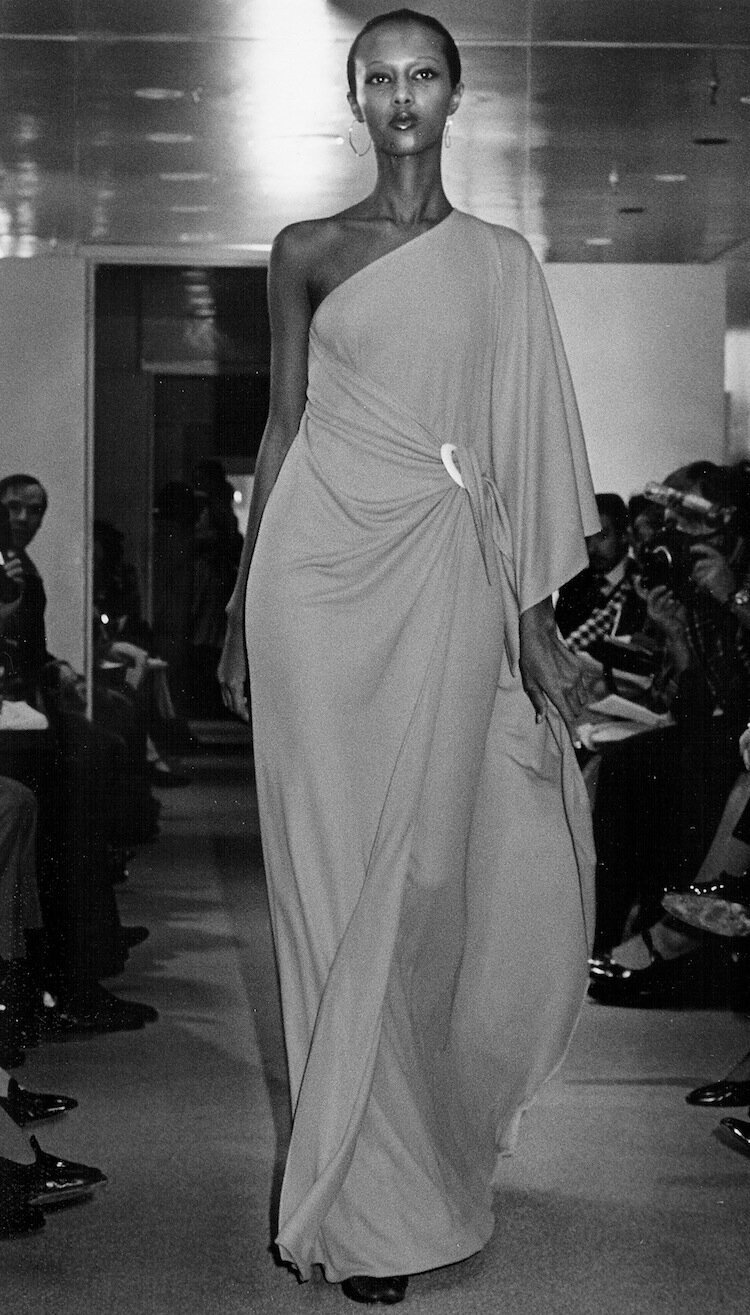

Hulanicki evolved her creations in step with changing tastes and appetites. There were slim trouser suits, with square shoulders and fitted sleeves. There were plunging necklines, wrap-over bodices and round-edged collars; culottes, coordinated separates and long diaphanous dresses. Whereas previously apparel retailers tended to offer longevity at a premium price, she made sure that there was a constant succession of fresh, affordable seasonal releases.

'We are determined that customers shall be able to buy summer clothes in summer and autumn clothes in autumn.’

Hulanicki took inspiration from history - from Victoriana, the Pre-Raphaelites, Art Nouveau and Art Deco; from Mucha, Mackintosh and Klimt. Biba’s celtic knot brand device, created by Anthony Little, echoed the illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley.

As well as working extensively in cotton, linen, chiffon, satin and velvet, Hulanicki experimented with heritage fabrics like marocain, flanesta, crepe and crepe de Chine.

‘We were always desperate for something different. We’d always had hundreds of fabric reps coming into Biba and we produced thousands of in-house prints.’

Early problems with sourcing prompted her to limit lines to 500 pieces in any one fabric. So the shop was always freshly stocked, and there was a sense of urgency when customers found something they liked.

‘Take it or leave it, but if you wait it won’t be there when you come back.’

Consequently, Hulanicki and Fitz-Simon established long-term relationships with textile manufacturers and attended countless textile fairs in the quest for ideas.

‘We went to all the fabric fairs: Milan, Bologna, Spain, Paris. I was obsessed. I had to see everything.’

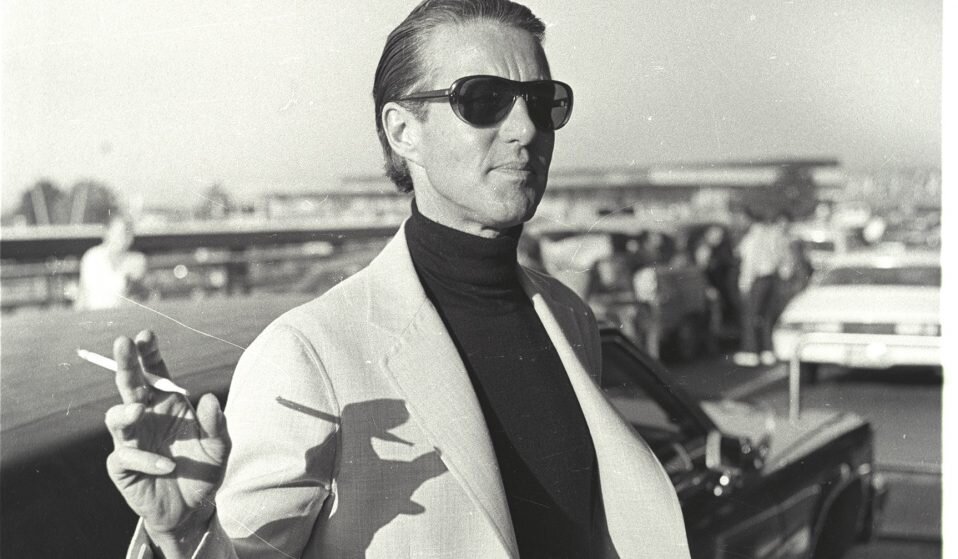

Barbara Hulanicki, 1964. © Barbara Hulanicki

The brand rapidly extended into menswear, unisex fashion and couture – and into children’s wear, which Hulanicki designed as scaled down versions of adult styles.

‘They have minds of their own. At three they come into us and choose everything, even their hats. They know what they want.’

The Biba look could be completed with accessories: floppy hats and elegant headscarves; colourful boots, plastic jewellery and feather boas.

‘First you’ve got the dress, then the tights, then the shoes, then the hat, and then you get to the face…and nothing.’

There was also a hugely successful range of cosmetics, sold through 300 Dorothy Perkins shops in the UK, and in more than 30 countries worldwide. Biba was the first company to produce a full range of cosmetics for both Black skin and for men.

Mail order took Biba garments and accessories nationwide in the UK. In the United States fabrics were sold with accompanying patterns through Macy’s, and a Biba department was set up in Bergdorf Goodman.

Biba at High Street Kensington became one of the most profitable stores in the world. It had over 100,000 visitors per week and an annual turnover of more than £200 per square foot (compared with £50 per square foot in an average department store).

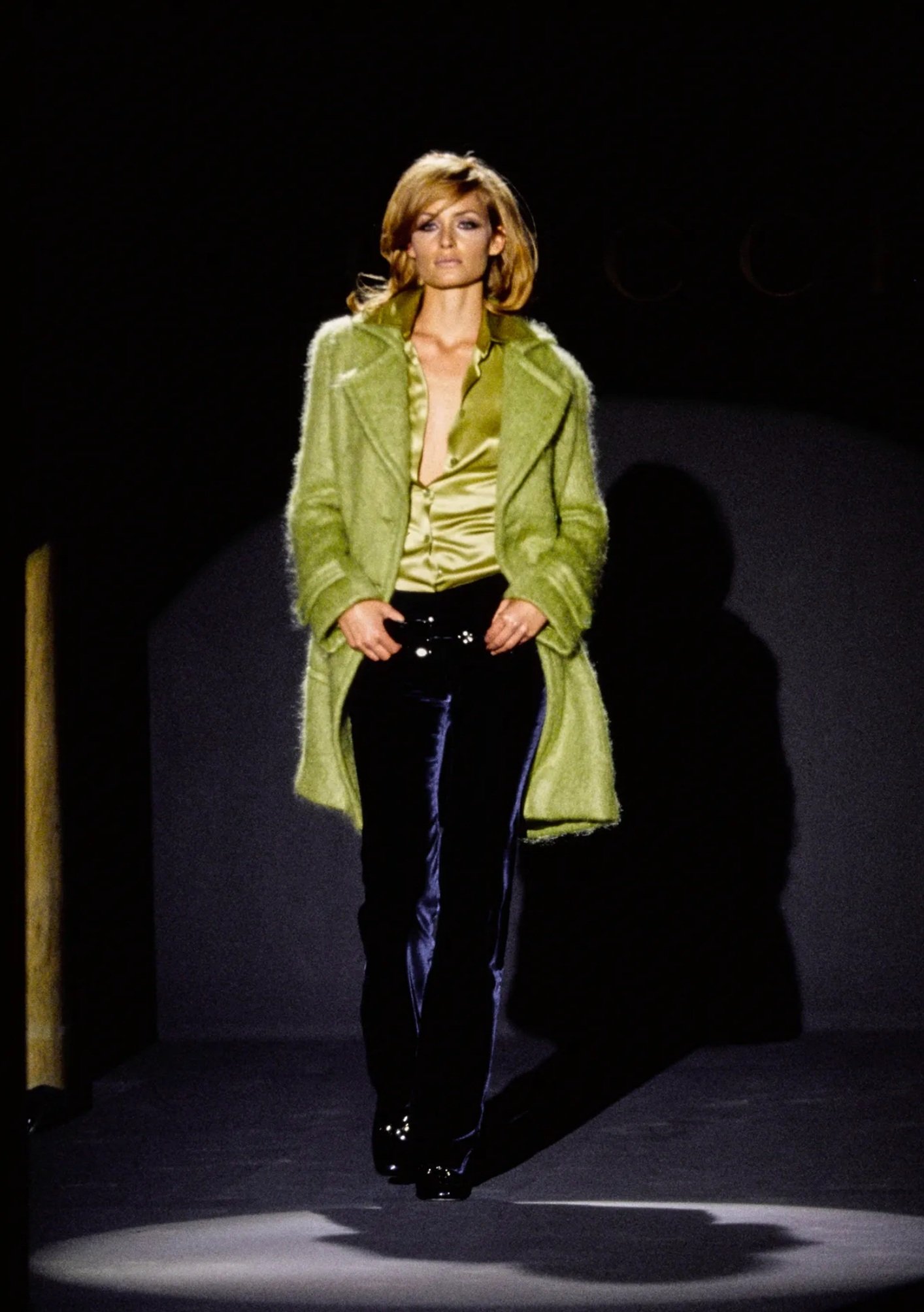

Twiggy in the Rainbow Room, Biba © Justin De Villeneuve and Iconic Images

‘When people like something, they need mark I, mark II and mark III. A progression.’

And so, in 1973, the brand scaled up yet again, with the launch of Big Biba, also on High Street Kensington. Spread over seven stories and fifteen departments, the store had an Art Deco interior celebrating the Golden Age of Hollywood. It sold Biba washing powder, baked beans, babies’ nappies and satin sheets. There was Biba wallpaper, paint, cutlery and soft furnishings. At Big Biba you could see an exhibition, visit a beauty parlour and take tea on Europe’s largest roof garden. In its Rainbow Room restaurant, you could watch bands like the New York Dolls, Cockney Rebel, the Pointer Sisters and Liberace.

The store attracted up to a million customers every week, its aesthetic chiming with the emergent glam rock movement. Freddie Mercury’s girlfriend Mary Austin worked there.

‘When [Queen] fans come over here, that ought to be the first place they go.’

Freddie Mercury

However, the stresses of running such a multi-faceted, endlessly changing fashion and lifestyle phenomenon became too much. Hulanicki and Fitz-Simon had sold 70% of the business to retailer Dorothy Perkins in 1969. Three years later Dorothy Perkins was taken over by property developer British Land, an owner that was unsympathetic to Biba’s creative culture.

‘Every time I went into the shop, I was afraid it would be for the last time.’

As well as the financial and workload pressures of running such a mercurial business, there were also challenges that came out of left field. In an episode that foreshadowed today’s ethical concerns about fast fashion, in 1971 the urban terrorist organisation The Angry Brigade (who had disrupted the Miss World competition the previous year) bombed the store.

‘Women are slaves to fashion, Biba leads fashion, therefore blowing up Biba will liberate Biba.’

The Angry Brigade

In the end Big Biba lasted just two years. Its fixtures and fittings were auctioned off and it was occupied by squatters. In 1975 it made way for a Marks & Spencer and a British Home Store.

‘I was okay for two days and then it hit me. I didn’t know who I was any more. Biba had been my life, my dream.’

Biba had been a revolutionary presence in the British fashion and retail world, ushering in the era of fast, affordable fashion and the lifestyle brand. It had shone brightly, fabulously, and then burnt itself out.

Twiggy in Biba © Justin De Villeneuve and Iconic Images

Biba teaches lessons about the dynamism of youth culture, the imperative of immediacy and affordability, the essential thrill of the retail experience and the relentless quest for inspiration. It also challenges us to manage brand extension with care; and to consider the social and environmental costs of fast fashion.

After the collapse of Biba, Hulanicki moved to Brazil, where she opened several stores and designed for labels such as Fiorucci and Cacharel. In 1987 she settled in Miami, where she ran an interior design business and worked as a consultant. She is still there today.

'Now, whenever I finish something, I take some photographs and say 'goodbye'. When you lose everything, you realise that the only thing you have is what's in your head.’

'I'm in with the in crowd, I go where the in crowd goes.

I'm in with the in crowd, and I know what the in crowd knows.

Anytime of the year, don't you hear? Dressing fine, making time.

We breeze up and down the street, we get respect from the people we meet.

They make way day or night, they know the in crowd is out of sight.

I'm in with the in crowd, I know every latest dance.

When you're in with the in crowd, it's so easy to find romance.'

Dobie Gray, 'The 'In’ Crowd’ (B Page)

No. 482