‘Kingdom of Dreams’: Learning from Luxury

‘The kingdom of dreams is this realm focused on creating fantasy, which was transformed into a global industry run by tycoons, who saw the value of these dreams and turned that into beautiful profits.’

Dana Thomas, fashion journalist and author of ‘Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Lustre’

I recently watched a splendid documentary series about the luxury fashion business.

‘Kingdom of Dreams’ ( written by Peter Ettedgui with Nick Green) recounts the rise of Bernard Arnault and his LVMH group, comprising elite labels like Dior, Louis Vuitton and Givenchy; his employment of maverick talent - John Galliano, Alexander McQueen and Marc Jacobs - to head up those labels; and his rivalry with Francois Pinault’s Gucci group, Domenico de Sole and Tom Ford.

‘Who is not amused by fashion? And even businessmen must amuse themselves from time to time.’

Bernard Arnault

It’s a story of bold vision and fierce ambition; of financial feuds and creative competition; of phenomenal commercial and artistic success, and the collateral damage that came in its wake. There are lessons to be learned by anyone working in an ideas business.

‘These brands have extraordinary evocative power, which allows the whole world to dream.’

Bernard Arnault

Bernard Arnault - Chairman and Chief Executive, LVMH

1. Acquire, Consolidate and Grow

Bernard Arnault, born in Roubaix in 1949, had a bourgeois upbringing in provincial France. After graduating from university, he joined his father’s civil engineering company, rising to president in 1978. In 1984 he acquired Boussac Saint-Frères, a once prosperous textile and retail conglomerate that had fallen on hard times, but whose assets included legendary luxury brand Christian Dior. He stripped the business of its loss making companies and made 9,000 workers redundant, thereby acquiring his nickname, ‘The Terminator’.

‘To be successful you need to dream. You do not need to be a dreamer, but you need to dream. And when you dream you can do things that are impossible.’

Bernard Arnault

In the 1980s the French fashion houses were in disarray. Though their products retained exceptional craftsmanship, couture had a narrow appeal to a predominantly European and American elite, and the brands had grown sleepy and stale. Arnault had a vision of reviving the sector, giving it more dynamic leadership and a broader, global target market.

‘We try to build a large business with one criteria: the best quality and the most elitist product in every level, that we are selling throughout the world.’

Bernard Arnault

In 1987 Arnault followed up his acquisition of Dior by engineering the merger of Louis Vuitton with Moët Hennessy. He was on a mission to acquire, consolidate and grow.

‘My vision of the future is that in 10 years time from now there will be fewer and fewer brands and that they will give even more power to the brands on the market at that time.’

Bernard Arnault

2. Awaken Slumbering Brands with Creative Talent

Though Arnault was tough and financially astute, he was well aware that the fashion business was founded on, and fuelled by, creativity.

In 1994 John Galliano presented his ‘jet-black’ collection for his own label. Staged on a shoestring budget, models Kate Moss, Helena Christensen, Naomi Campbell and Linda Evangelista waived their regular fees to participate. In a dramatic show the Paris mansion of Portuguese socialite Sao Schlumberger was littered with dried leaves, red rose petals and discarded chandeliers. It became a legendary fashion moment.

‘I dare people to dream.’

John Galliano

John Galliano, Photograph: Jacques Brinon/AP

A year later Arnault appointed the young British-Gibraltarian as creative director of Givenchy.

Galliano set about researching Hubert de Givenchy’s work for Audrey Hepburn and Jackie Kennedy, and presented his first couture show for the house in 1996. He was a sensation from the start, reintroducing romance and theatre to the label. Arnault was so impressed that, later that same year, he transferred Galliano to Dior.

‘I think the key of success in a brand as famous as Dior… is to have such a level of creativity and inventiveness.’

Bernard Arnault

This left a vacancy at Givenchy, which Arnault promptly filled with another Brit, Alexander McQueen – a daring and provocative designer, renowned for his exquisite tailoring and historical themes.

‘I don’t beat around the bush when I do a show. I go straight for the jugular.’

Alexander McQueen

McQueen with Model © Salons Galahad Ltd

Then in 1997 Arnault chose American Marc Jacobs to lead Louis Vuitton. Jacobs promised to bring street style and musical inspiration to the world of high fashion.

‘I wanted to create a collection that was basically visual noise.’

Marc Jacobs

And so, in short order, a new cohort of gifted creative directors had been installed across the three major houses at LVMH.

‘I believe we have found the right designers for each brand.’

Bernard Arnault

3. Find Eyes and Ears

In making the critical initial selection of Galliano, Arnault had sought a fashion insider’s perspective, turning to Editor of American Vogue, Anna Wintour.

‘Obviously at the time it was a risk. But I was comforted by Anna about what [Galliano] could do, and finally I took the risk. She’s an eye. To have an eye is key.’

Bernard Arnault

As Arnault built his stable of luxury brands, Wintour continued to provide priceless expertise and insight.

‘I don’t think of myself as a boss. I think of myself as someone who’s giving direction, guidance. I try to be decisive even if I don’t know what the hell I’m doing.’

Anna Wintour

4. Make Noise

Arnault’s young creative directors were not all successful from the outset. McQueen’s first efforts for Givenchy were regarded as missteps. And in his first ready-to-wear collection for Louis Vuitton, Jacobs failed to present any bags.

‘I was a little bit – how shall I put it? – astonished, because there wasn’t a single bag in the first show.’

Bernard Arnault

But Arnault stuck with his choices. And to some extent what the designers were contributing was more precious than any particular collection. They introduced youth, energy and excitement.

‘It didn’t matter. That’s the whole point of it. It still made people talk. It was about making noise.’

Dana Thomas

Shalom Harlow being spray-painted by robots in the Alexander McQueen spring 1999 show

5. Encourage Constructive Rivalry

It could not have been easy housing so much creative talent under one corporate roof. But Arnault was happy to nurture a certain amount of constructive rivalry.

‘John’s more fluid and romantic. He has a great vision for romanticising his ideal woman. I think I really care about a woman’s independence. I don’t like her to look so naïve and so fragile. I like her to look stronger.’

Alexander McQueen

6. Have a Winning Instinct

In building the LVMH empire, Arnault attracted his critics. Many were concerned by his import of American-style corporate aggression to Europe; by his hostile takeovers and the swift removal of the luxury houses’ elderly family members.

‘I think he wants to be a wolf because he needs people to be afraid of him.’

Mimma Viglezio, Gucci

Certainly Arnault displayed a competitive streak, an absolute conviction that he must win at all times and at all costs.

‘Material things have never motivated me. What drives me is to make my company win. Making it the top company in the world, that’s what drives me above all.’

Bernard Arnault

7. Seize the Lucky Moments

Meanwhile in Milan the house of Gucci was beset by dysfunction: lawsuits, tax evasion and family feuds. In 1995 Maurizio Gucci was shot dead in the lobby of Gucci's Milan office.

Harvard educated Domenico de Sole had been legal adviser to the Gucci family since the 1980s and CEO since 1994. Facing corporate bankruptcy, he couldn’t afford a big name designer, and so promoted from within, appointing the relatively unknown head of knitwear, Tom Ford, as creative director.

‘In life being lucky is much better than being smart. Because as much as I thought Tom was terrific, I never imagined that he’d turn out to be a genius.’

Domenico de Sole

Elegant Texan Ford had not risen to the top by the conventional route. He graduated in architecture and his fashion career began as a PR at Chloé. After a couple of years designing for Perry Ellis, he decided to try his luck in Europe, taking a role at the struggling Gucci.

‘You have to be ready for those lucky moments to cross your path and you have to seize them.’

Tom Ford

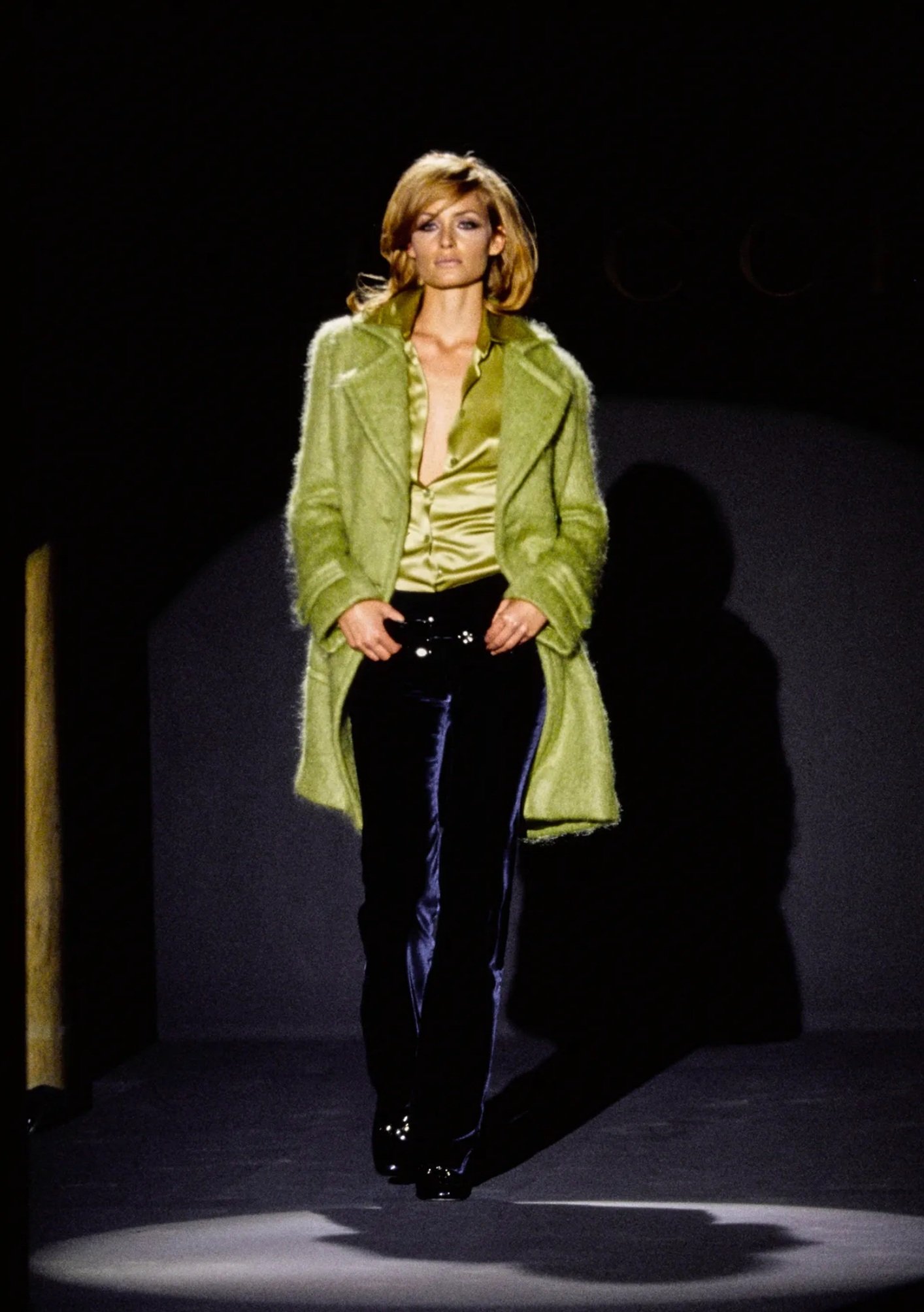

Ford's Fall 1995 ready-to-wear collection for Gucci, with its metallic patent boots and velvet hipsters, unbuttoned satin shirts and sensuous ‘70s glamour, was a huge hit and earned the immediate endorsement of celebrities like Madonna.

‘The right thing at the right time is the right thing. The right thing at the wrong time is the wrong thing. So it’s got to be the thing that people want before they know they want it.’

Tom Ford

8. Find a Partner You Can Trust

‘You design, I run the company. It will be OK. At least we will give it a try.’

Domenico de Sole

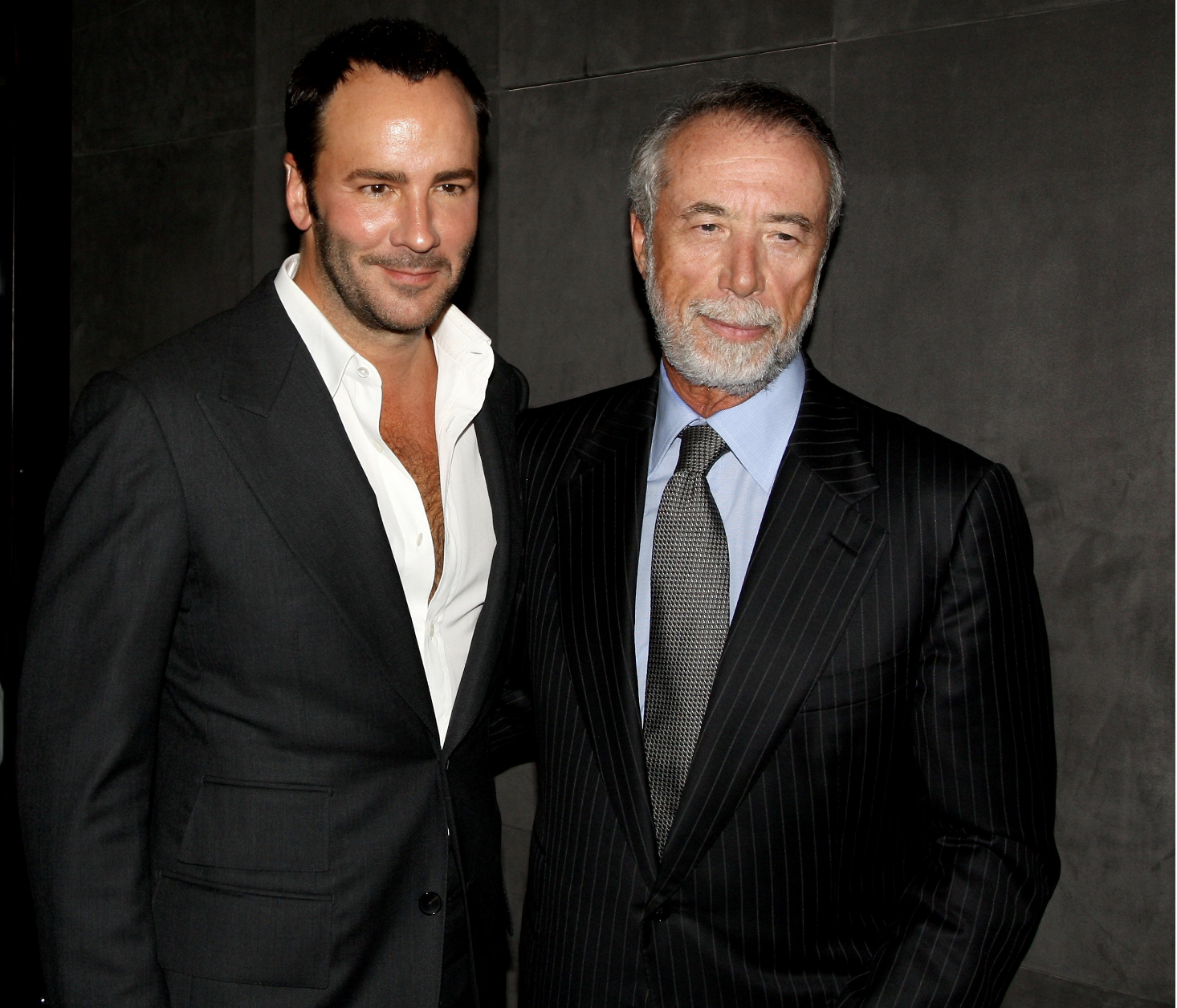

The successful revival at Gucci was very much down to a happy partnership between commercial and creative expertise. Ford and de Sole understood that each had a different but crucial role. They respected each other.

‘He completely trusts me on the design side. Domenico I completely trust on the business side. And so in a sense we can work independently and together, which I think really makes us almost twice as strong as a lot of our competitors.’

Tom Ford

Tom Ford and Domenico de Sole. Getty Images

9. Keep an Eye on Adjacent Opportunities

Another factor in Gucci’s success at this time was Ford’s decision to send every model down the runway carrying a Gucci bag. Handbags commanded high margins and became a booming business in their own right.

At a 1996 event in New York to mark Dior’s 50th anniversary, Galliano was commissioned to design a gown for Princess Diana. The midnight blue satin and lace sheath dress was not considered a success. Some wags dubbed it a ‘nightie.’ But the mini blue satin bag she carried was subsequently sold the world over.

Marc Jacobs had been struggling at Louis Vuitton. But in 2001 he partnered with graffiti artist Stephen Sprouse to reinvent the branding that appeared all over its luggage – a bold move that was wildly popular, and in one leap revitalised the label.

‘He gave it a youth, a modernity and a wonderful sense of fashion. And now everybody wants the luggage again. And they want the clothes.’

Anna Wintour

Clearly success in the luxury fashion business was about more than couture. One had to take a holistic view and keep an eye on adjacent opportunities.

10. Fight for Your Independence

In the wake of its revival, Gucci became one of the first European luxury houses to go public on the stock market. But this left it vulnerable to takeover. In particular it became a target for Arnault, who had been impressed by the brand’s renaissance and wanted Ford at LVMH.

‘I think Mr Ford is amazing. There’s no reason at all for him to be nervous… If you see him please do let him know.’

Bernard Arnault

Ford and de Santo were concerned about the prospect of Arnault’s assertive ownership and wanted to retain autonomy. They stalled by issuing shares to employees, and found themselves in a prolonged and very public court battle with Arnault as a result. At length they sought a ‘white knight’, a ‘friendly’ investor to save Gucci from a hostile takeover.

They found Francois Pinault - a tycoon who had built his fortune in distribution and then retail. Unable easily to internationalise his retail business, he saw in luxury goods an opportunity to go global.

‘There’s no greater risk than believing you’ve succeeded. It’s dangerous to rest on your laurels. You have to seek out new adventures, new businesses.’

Francois Pinault

Pinault was the opposite of Arnault in upbringing and style. Whereas Arnault had a bourgeois background, Pinault came from a modest rural French family, leaving school at 16 to work in his father’s lumber company. Whereas Arnault planned ahead and acted by stealth, Pinault tended to be instinctive and decisive.

‘I make quick judgements and my first impression is usually right.’

Francois Pinault

In 1999 Pinault purchased a controlling stake of the Gucci group for $3 billion and bought Yves Saint Laurent the same year. He followed up by purchasing Boucheron in 2000 and Balenciaga in 2001.

‘We’re looking for companies where we believe that our expertise could enhance the value of that company and thus enhance the value of Gucci group.’

Tom Ford

Arnault was not accustomed to losing. Confronted with the birth of a competitive luxury powerhouse, he fumed from the sidelines.

‘Now [Ford] has found a white knight. But you know, sometimes a white knight becomes a black knight. So we’ll see how long it lasts.’

Bernard Arnault

François-Henri Pinault. Jude Edginton

11. Put Creativity and Commerce in Harness

In this golden age for elite fashion brands, as the two luxury leviathans fought for dominance, they expanded across categories and geographies, pulling in new consumers who were united in their desire for status and beauty.

‘My goal is to create something that’s beautiful - something that’s so beautiful that people can’t live without it. And when you do that people buy it, it makes sales. And when you make sales, you make money. And that’s what my job is.’

Tom Ford

At their best the luxury groups harnessed creativity to commercial goals.

‘John [Galliano] is about pure creativity. But also he likes to do products that sell. Since he arrived sales have tripled. So what he does is really not only pure creativity, but also what the ladies, the consumers, want to wear.’

Bernard Arnault

If the creative directors continued to deliver designs that sold, then the business leaders, shareholders and investors were happy.

‘[Galliano] has absolutely carte blanche - as long as the business is going out, the business is booming. So he has carte blanche.’

Bernard Arnault

12. Beware: Things Fall Apart

However, the seemingly perfect marriage of commerce and creativity was flawed. Fundamentally the corporate chiefs did not share the same goals as their designers.

‘Bernard Arnault was extremely supportive of his star designers, and he really did believe in them. But his goals and their goals were different. For them money was the bi-product of their talent and their work and their dedication to their passion. For Arnault money was the goal.’

Dana Thomas

Gradually things fell apart.

Firstly the constructive rivalry at LVMH began to fracture. McQueen became frustrated with the smaller budgets that were available to him at Givenchy and with what he perceived as Arnault’s favouritism.

‘[Arnault’s] got great vision. But his vision of what I was like was the same vision as what John [Galliano] was like. Maybe John was more pliable than I was.’

Alexander McQueen

McQueen felt he was not valued.

‘You’ve got to feel the appreciation back. You can only keep on going on for so long.’

Alexander McQueen

So McQueen began saving his best ideas for his own label, raiding the Givenchy stores for fabrics and redirecting funds. And in 2000 he jumped the LVMH ship and joined Gucci group in a deal that enabled him to expand his own label.

For a while McQueen thrived, becoming healthier and happier.

‘When I signed for Gucci I continually pushed myself to be stronger physically and mentally. And this is the outcome.’

Alexander McQueen

However, as Ford and de Sole came to renew their contracts with Pinault, there was a falling out, and in 2004 they left the group.

‘Tom Ford and Domenico de Sole believed that Gucci belonged to them. They forgot that I was the biggest shareholder. They wanted to pursue an agenda I didn’t agree with. So one day I told Tom Ford: ‘You’re out.’ He just didn’t understand. He thought Gucci was his.’

Francois Pinault

Ford was devastated.

‘I all of a sudden felt lost. I felt: ‘What do I contribute to the world? What am I doing? Who am I? What is this?’ Because I had worked so hard for so long, and I didn’t really realise how it would feel when I no longer had that platform or that voice. And I felt quite lost.’

Tom Ford

With Ford and de Sole gone, McQueen was isolated.

‘It can be really lonely. And I think there’s more to life than fashion. And I don’t want to be stuck in that bubble of ‘This is what I do.’ Because everyone in the office, they can go home and they can shut off. But I’m still Alexander McQueen after I shut the door.’

Alexander McQueen

In 2010, shortly after the death of his mother, McQueen took his own life. He was 40.

Meanwhile, over at LVMH, Galliano had increasingly struggled with the work pressures that came hand-in-hand with his accomplishments.

‘Along with the success came more collections. At that moment I was producing 32 collections a year between the House of Galliano and the House of Dior, and each collection would comprise up to a thousand pieces. The drinking did creep up on me.’

John Galliano

In the same year that McQueen died, a drunken Galliano was filmed in a Paris bar directing antisemitic slurs at a group of women. He was fired from Dior.

Jacobs too had issues with alcohol and substance abuse.

‘I don’t deal with pressure too well. I go off my diet. I smoke twice as many cigarettes and I sometimes get a little angry, rude… I don’t think I deal with it so well.’

Marc Jacobs

Marc Jacobs

In 2013, after 16 years as artistic director at Louis Vuitton, Jacobs presented his last show for the label.

13. It’s Not What Brands Are, But What They Represent

The demise of McQueen, Galliano and Jacobs marked the end of the era of maverick creative directors at the luxury houses.

‘Super-strength designers were absolutely crucial to a particular phase of the luxury industry – which was building it up from being a name to being a brand. But once they had become real brands, they were businesses and therefore you could find people to work in that business who have creativity, but who are a bit less larger-than-life than some of these designers were at the time.’

Thomas Kamm, PPR

LVMH and Gucci group had driven a phenomenal period of growth and expansion in the luxury goods sector. But they had transformed it into a completely different business.

‘The frenzy for these logos - fuelled by celebrities, the billboards, the magazine ads, the commercials, the placement in movies, the logo-heavy marketing – switched the reason everyone had purchased these products in the first place from what they were – beautiful, handcrafted luxury items, rare, special – into what they represented – wealth, success, power.’

Dana Thomas

'It seems the Babylon dem

Come fight 'gainst I,

Dem-a fight 'gainst I.

I wanna know the reason why.

Babylon fight 'gainst natty dread.

Babylon no fight 'gainst the rum head.

Babylon no fight 'gainst the wine head.

Only natty dreadlocks.

Natty dreadlock in a Babylon.’

Sylford Walker, ‘Burn Babylon’ (S Walker, J Gibson)

No. 408