Mary Quant: Becoming Bored Before Everyone Else

'All a designer can do is anticipate a mood before people realize that they are bored. It is simply a matter of getting bored first.’

Mary Quant

I recently enjoyed the documentary ‘Quant,’ celebrating the life and work of fashion designer Mary Quant (2021, directed by Sadie Frost).

'Fashion is a tool to compete in life outside the home. People like you better, without knowing why, because people always react well to a person they like the looks of.’

Quant, who passed away last year at the age of 93, brought affordable fun, freedom and comfort to female fashion. She designed for the Chelsea Girl, a young, emancipated working woman who kicked against tradition and convention. She introduced short, simple, streamlined garments, in bright, bold colours and patterns, worn with flat shoes and sharp haircuts. She democratised the jersey dress, the miniskirt, tights and trousers; skinny rib sweaters and PVC rainwear. She grew a successful business that expanded internationally and beyond clothes into make-up and homeware. And she taught us some compelling lessons about the creative mindset.

'Rules are invented for lazy people who don't want to think for themselves.’

1. Speak Like a Child

'I grew up not wanting to grow up.’

Barbara Mary Quant was born in 1930 in Woolwich, London, the daughter of Welsh schoolteachers. She had a blissful childhood, running wild with her younger brother in the Pembrokeshire countryside.

‘I was the usual split personality as a child. One minute climbing trees, only wanting to play with boys and throw stones and steal apples and the rest of it. But equally there was the other side, where I just adored dolls and clothes.’

Quant found adulthood an unattractive prospect.

‘The day I was 13 I cried all day because old age had struck… Growing meant to me getting into stockings and suspenders… and high heels and having artificial hair and artificial nails. You know, a bosom that came into the room about 2 minutes before the rest of you.’

2. Find the Outcasts

Quant studied illustration and art education at Goldsmiths College, one of a number of British art schools that were inspiring a new generation at the time. She found true soul mates there.

‘We saw ourselves as sort of outcasts really, and trying to somehow gang together in Chelsea with a very few other people who felt as outcast as we did.’

Goldsmiths taught Quant to see the world differently.

‘We didn’t like the way things were, didn’t like the way things looked, the way people lived.’

3. Don’t Be Tasteful, Be Vulgar

Britain in the 1950s was a bleak, austere country, still recovering from World War 2, and young people were determined to change things.

‘We’d won a war and lost so much at the same time. There was a new generation that came romping through with high confidence and high spirits, and the generation that should have been there to control everything just let us do it.’

After finishing her degree, Quant pursued her fashion ambitions with an apprenticeship at a Mayfair milliner.

High-end design was at the time dominated by Christian Dior’s New Look, which, despite its name, was nostalgic for pre-war times. Quant instinctively felt uneasy with couture’s elite customer base and its establishment views.

‘We don’t want to look like a duchess…. Good taste is death. Vulgarity is life.’

4. Find Partners with Complementary Skills

At art school Quant had met her future husband and business partner, Alexander Plunket Greene. While she was somewhat diffident and reserved, he was a tall, charming, fun-loving aristocrat. He became a natural PR-man for Quant’s work.

‘Nobody said you can’t do it. We just did it.’

With £5000 that Plunket had inherited, and with financial advice from the entrepreneur Archie McNair, in 1955 Quant took a mortgage on a property on the King’s Road, Chelsea and opened her first boutique, Bazaar.

5. Risk It, Go for It

Bazaar was unlike the tired department stores and inaccessible designer shops of the time. The boutique had music, drinks and long hours for its customers’ convenience. It was also cramped and somewhat chaotic, with shoppers often changing on the shop-floor among packing cases.

‘Nobody said you’re not supposed to do it like that.’

The displays featured mannequins in quirky poses, which drew queues of curious young women and prompted angry bowler-hatted men to beat their fists on the windows.

'Risk it, go for it. Life always gives you another chance, another go at it. It's very important to take enormous risks.’

6. Design For People Like You

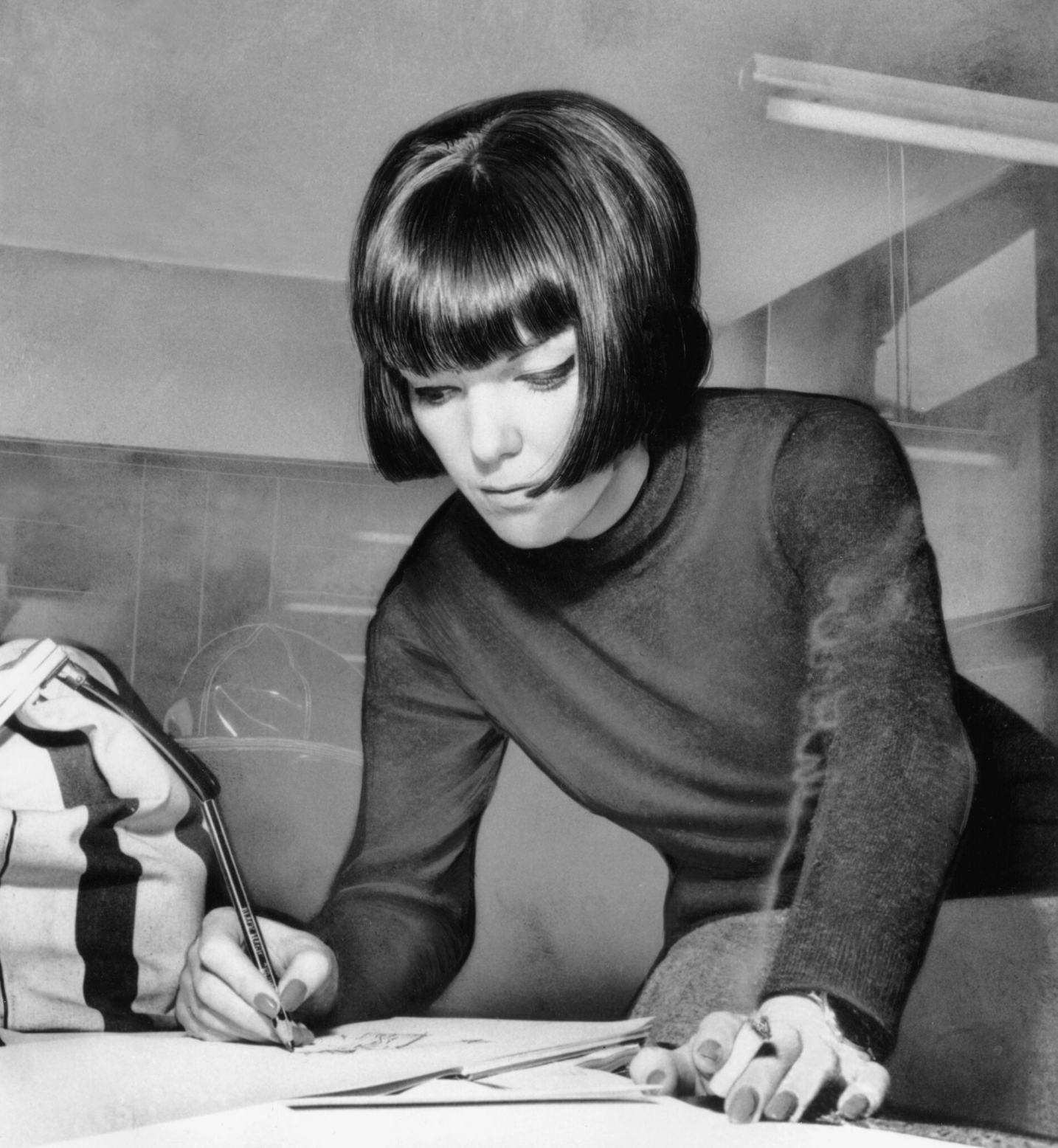

With her lean figure and short, geometric Vidal Sassoon bob, Quant embodied a youthful new style.

‘I just started making and designing clothes for people like me.’

She set about creating short, narrow, simple garments in an array of bright, bold colours and patterns. Shift dresses and pinafores, trousers, breeches and knickerbockers - clothes that promised comfort, fun and freedom of movement.

‘The clothes were very short and very simple. The shoes were very flat, so that you could run, dance, jump. All the clothes were very simple, but put together they had a very strong look.’

7. Be Inspired by Adjacent Worlds

Quant sought inspiration in the fashion worlds adjacent to womenswear.

'I liked masculine fabrics: Prince of Wales checks, city pinstripes and flannels - worn with black tights, flattish shoes.’

Trousers had for some time been worn by women in Hollywood and the services, and by students. But Quant popularised them for young females, introducing spotted cropped pants, breeches and dungarees. She also elongated men’s shirts into dresses and lengthened men’s cardigans.

‘Clothes are a statement about oneself or what one wants to be.’

The jumpers that she wore as a child prompted her to design skinny-rib sweaters. And her trips to the United States suggested the idea of ‘homewear’- special clothes for lounging in at home - 'underwear as outerwear.'

‘I hated fashion the way it was. I wanted clothes to be far more casual and easygoing and yet still sexy.’

8. Be inspired By Your Audience

'I liked my skirts short because I wanted to run and catch the bus to get to work.’

Skirts had been getting shorter since the 1950s, and the designer André Courrèges took them above the knee in the early ‘60s. But it was Quant who made the miniskirt mainstream, naming it after her favourite make of car.

Male Interviewer: Few girls have the legs, hips and, above all, panache to carry it off majestically.

Quant: But who wants to be majestic?

Quant was keen to point out that the driving force behind this fashion revolution was the consumer herself: the liberated, working woman, the Chelsea Girl.

'It was the girls on the King's Road who invented the miniskirt. I was making easy, youthful, simple clothes, in which you could move, in which you could run and jump and we would make them the length the customer wanted. I wore them very short, and the customers would say, 'Shorter, shorter!’'

The convention in those days was for women to wear stockings, often in 'American Tan', held up by garters and suspender belts - all very fiddly and uncomfortable. As Quant cut her skirts shorter, so she promoted tights to go with them - in black, and in bright mustard, ginger and prune.

‘I think a revolution was going on which fashion people hadn’t realised. I think the change of focus had gone from the rich international couture thing to the young working girl. She was going to set the pace in fashion, decide what was right and what was wrong.’

9. Be Inspired by Technology

Quant also turned to the latest technology for ideas.

‘The modern look is sexy, pretty, polished and dry cleaned.’

Jersey, a material traditionally used in men’s underwear, had been adopted by Coco Chanel for daywear in the 1920s and ‘30s. Quant employed new synthetic fabrics like Crimplene and Acrilan, which could be mass-produced at low cost. Her jersey dresses came in numerous colours and shapes, with different collars, sleeves, zips and buttons.

‘Sometimes all ideas come from the technology and sometimes the other way round.’

Quant was also fascinated by the space-age possibilities afforded by polyvinyl chloride (PVC), ‘this super shiny man-made stuff and its shrieking colours.’ Her 1963 'Wet Collection' featured entirely PVC garments, combining functionality with striking visual effects.

'Fashion is not frivolous. It is a part of being alive today.’

10. Be Permanently Dissatisfied

As Quant grew more successful in the UK and abroad, she remained restless to invent new designs and explore new frontiers.

'Fashion is a very ongoing, renewing thing, about change and reaching for the next thing. You are permanently dissatisfied, and it's always got to get better.’

In particular, she became frustrated with the cosmetics that women were wearing with her clothes.

‘I got involved with make-up because now that the clothes were different, the face was wrong.’

Tired of the ornamental nature of incumbent products, and inspired by the more theatrical make-up employed by catwalk models, in 1966 Quant launched a cosmetics line of bold shades in a simple all-in-one paintbox package, and featuring her trademark daisy logo.

‘I think the point of clothes for women should be: 1. that you’re noticed; 2. that you look sexy; and 3, that you feel good. I can’t see that we wear them to keep warm.’

11. Be Stubborn

As a female entrepreneur working in a still predominantly male environment, Quant had to endure a good deal of sexism. She was clearly incredibly resilient.

'The fashionable woman wears clothes. The clothes don’t wear her.’

In the documentary Quant tries to explain her vision for a new fragrance line to a sceptical male perfumier.

Quant: It seems to me that to be a woman now is a very schizophrenic situation… And I think this perverse schizophrenia is the mood I would like to arrive at.

Perfumier: Yes, I would agree entirely. But I think that to satisfy that you have to come up with two types of perfume.

Quant (Impatient): But it’s the same woman!

12. Retain Creative Control

As Quant’s business expanded across the world, so did the pressure on her to keep producing new designs; to maintain the machine.

'One of the things I've learned is never to hoard ideas, because either they are not so relevant or they've gone stale. Whatever it is, pour it out.’

Quant turned to licensing her brand to sustain its success.

‘Licensing allows you to extend your brand to new markets, new areas, new categories. Which can be very exciting for a brand. But it’s about control and it’s about a sense of understanding between the licensee and the licensor. That’s where you’ve got to get it right.’

Inevitably Quant did lose some of her creative control in these deals. In the documentary she complains that one of her commercial partners wants her to remove the pockets from a dress design.

'Well, you know, he’d like to get rid of these pockets all together. I think it makes the whole thing. And it’ll save him 10 pence.’

13. Live in the Future

'Most of my memories of the ‘60s are ones of optimism, high spirits and confidence.’

As the ‘60s drew to a close the mood changed from optimism about the future to one of disillusion and protest. Fashion turned to Bohemian and ethnic styles; to floaty dresses and flared, faded jeans. Quant’s modernism seemed less relevant.

'The whole 1960s thing was a ten-year running party, which was lovely. It started at the end of the 1950s and sort of faded a bit when it became muddled with flower power.’

Bazaar closed in 1969, and through the ‘70s and ‘80s Quant concentrated on household goods and make-up. In 2000 she resigned as director of Mary Quant Ltd after a Japanese buy-out.

Mary Quant had anticipated the Swinging ‘60s and come to embody its lean, fun-loving, modernist attitudes. She had changed the way British women dressed and thought about clothes.

‘Fashion is all about change. And I’m designing for the future.’

As well as being a revolutionary designer and resolute businesswoman, Quant was articulate about the role of fashion in women’s lives.

‘Fashion is for now, not necessarily for teenagers... If you’re still enjoying living and you’re still enjoying being a woman and being sexy and being alive, then one wants surely to wear the clothes of today.’

I was particularly struck by the way she characterised ennui as a positive and productive force in consumer culture.

‘I think that a designer has to be someone who is permanently bored – permanently bored with the way people look at any particular time, wanting to live in the future, wanting to change things.’

Quant suggests a compelling challenge for creative people working in any industry: become bored before everyone else!

'I just don't know what to do with myself.

Don't know just what to do with myself.

I'm so used to doing everything with you,

Planning everything for two,

And now that we're through.

I just don't know what to do with my time.

I'm so lonesome for you it's a crime.

Going to a movie only makes me sad.

Parties make me feel as bad.

When I'm not with you

I just don't know what to do.

Like a summer rose

Needs the sun and rain,

I need your sweet love

To beat all the pain.’

Dusty Springfield, 'I Just Don’t Know What to Do With Myself’ (B Bacharach, H David)

No. 472