The Band Wagon: You Can Teach an Old Dog New Tricks

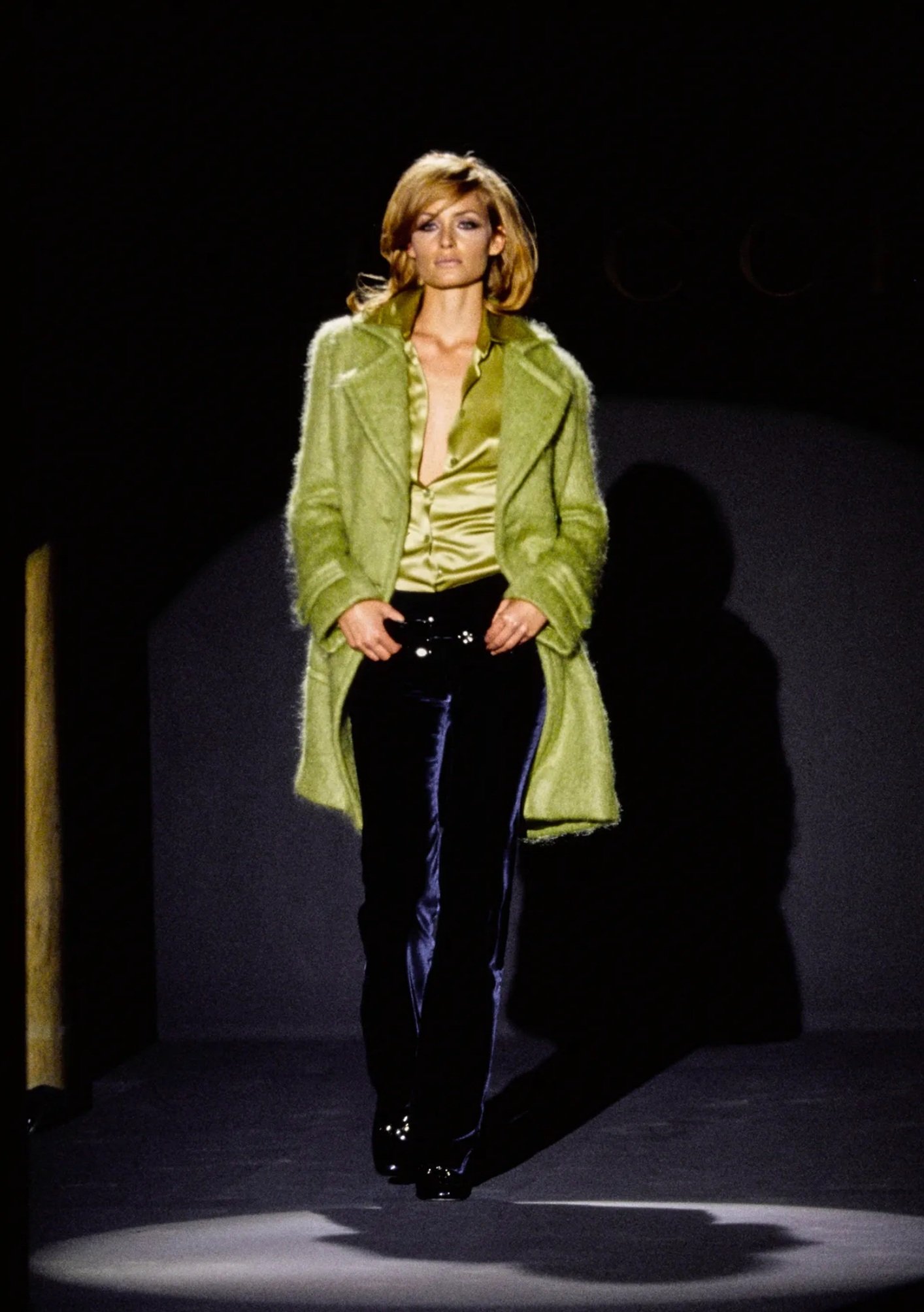

The Band Wagon, From Left Cyd and Fred Astaire. Photo - Everett

‘The Band Wagon’ is a fine 1953 musical comedy, directed by Vincente Minnelli with songs by Schwartz and Dietz. Starring Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisse, it boasts great tunes and cracking dance routines. And it explores some important themes: the interaction between aging talent, timeless skills and contemporary relevance; between entertainment and art, populism and pretension.

The film begins with the auction of a top hat and cane that once belonged to Tony Hunter (Astaire), the star of now dated dance movies. No one is interested in making a bid. We join Tony on a train from Hollywood to New York where he overhears fellow passengers discuss him as a has-been. At Grand Central he is heartened to see a crowd of reporters, but they are there to greet Ava Gardner. He realises he’s all washed up.

'The party's over, the game is ended,

The dreams I dreamed went up in smoke.

They didn't pan out as I had intended,

I should know how to take a joke.’

‘By Myself’ (A Schwartz / H Dietz)

Nonetheless, Tony is welcomed at the station by his friends, songwriting duo Lester and Lily Marton. They have composed a light musical comedy that will make a perfect Broadway comeback for him. And they are excited to have caught the interest of avant garde theatre director Jeffrey Cordova.

When the team meet up with Cordova, he enthuses about the project. He proposes to bring together diverse performance traditions into something startlingly new; to create a radical reinterpretation of the Faust legend.

To accommodate the director’s vision, the Martons rewrite their play as a dark, cutting edge musical drama. And Cordova signs up youthful ballerina Gaby Gerard (Charisse) as Tony’s partner.

Tony, however, is apprehensive about starring opposite a classically trained ballet dancer, and one so tall. And Gaby is nervous about working with a Hollywood legend. Their initial meeting goes badly.

Gaby: I'm a great admirer of yours too.

Tony: Oh, I didn't think you'd ever even heard of me.

Gaby: Heard of you? I used to see all your pictures when I was a little girl. And I'm still a fan. I recently went to see a revival of them at the museum.

The company embarks on rehearsals. But Tony, feeling he's being patronized by the creative team, storms out.

'Let's get this straight. I am not Nijinsky. I am not Marlon Brando. I am Mrs Hunter's little boy, Tony, song and dance man.'

When Gaby’s attempt to patch things up with Tony goes awry, she bursts into tears. They decide to clear the air with an evening carriage ride and walk through Central Park.

'Where to?'

'Oh, leave it to the horse.'

Strolling under a full moon, they reach a clearing. They walk slowly, in step, without a word - he in a cream linen jacket with yellow shirt and tie, she in a simple white dress. She spins. He spins. They sway together - he with his hands behind his back, she with her hands by her sides. They rotate, skip, twist and turn. At first gently, thoughtfully. Gradually they become elegantly entwined, and as the swooning string music is punctuated by stabs of brass, the extensions become more dramatic, the embrace more intimate. He lifts her up and they look into each other’s eyes. They flutter gracefully up a set of steps and settle back into the carriage, hand in hand, without a word.

This famous ‘Dancing in the Dark’ sequence establishes that Gaby and Tony make natural dance partners. They recommit to rehearsals with renewed vigour.

However, the first out-of-town tryout of the show proves disastrous. It’s a hugely complicated production, with elaborate sets and muddled stage direction, and it degenerates into a farce.

'You got more scenery in this show than there is in Yellowstone National Park!’

'I should have listened to my mother. She told me only to be in hit shows.’

At Tony’s insistence, the creative team convert the production back into the light comedy that the Martons had originally envisaged. At last it all comes together.

The show's centrepiece is a 12-minute dance tribute to pulp detective novels. ‘Girl Hunt’, a murder mystery in jazz’ relates a private eye’s adventures on the city’s mean streets. There’s a blonde in distress, who’s ‘as scared as a turkey in November,’ and a sinister brunette with ‘more curves than a scenic railway.’ There’s a gunfight in the subway and trilbied villains at a fashion show; an emerald ring, exploding bottles and a murderous trumpet player. And it all climaxes in Dem Bones Café with Charisse in shimmering red dress and black evening gloves, all sensuous strut, long legs and high kicks.

‘She was bad. She was dangerous. I wouldn't trust her any farther than I could throw her. But... she was my kind of woman.’

After the thrillingly successful Broadway opening, Gaby and Tony embrace in front of the entire cast and crew.

'The show's a big hit, Tony... It's going to run for a long time. As far as I'm concerned, it's going to run forever.'

So what are we to make of the underlying themes of ‘The Band Wagon’?

There’s no doubt the project had personal resonances for Astaire. He was 54 and had been indelibly associated with high society dance movies. He often worried about taller partners and had previously considered retirement.

At first the film seems to be an assertion of the enduring power of established craft in the face of contemporary trends and pretentious art-house conceits. But Tony’s ultimate success does not reside in him returning to the top-hat-and-tails tropes of yesteryear. Rather he forges a new, more inventive form of popular entertainment, based on a natural partnership with a star from another discipline.

It suggests that traditional skills can remain relevant - not by grafting them onto the latest fad or fashion - but by investing them with new vigour, input and imagination.

As the cast declare in a final reprise of the show’s big hit: ‘That’s entertainment!’

'Everything that happens in life

Can happen in a show.

You can make 'em laugh,

You can make 'em cry,

Anything can go.’

’That’s Entertainment’ (A Schwartz, H Dietz)

No.414