Sandwich Salvation at Clyde’s Truck-Stop: We All Need Something to Believe In

‘The sandwich is your pulpit, it’s where you preach the gospel of good eating.’

I recently saw ‘Clyde’s’, a play by Lynn Nottage currently at The Donmar Warehouse, London (directed by Lynette Linton, until 2 Dec).

Montrellous: This sandwich is the culmination of a long hard journey that began with a wheat seed cultivated by a farmer thousands of years ago.

This splendid work is set in the bustling kitchen of a Pennsylvania truck-stop staffed by ex-offenders. It’s the story of damaged lives and second chances; of confronting hard choices and recovering self-esteem; of finding salvation in a sandwich.

Montrellous: I think about the balance of ingredients and the journey I want the consumer to take with each bite. Then, finally, how I can achieve oneness with the sandwich.

Proprietor Clyde (Gbemisola Ikumelo) is a ruthless tyrant in high-heeled ankle boots. She has served time herself, and rules the business with an iron fist, periodically popping her head through the serving hatch with blunt demands for harder work and faster service.

Clyde: Social hour’s over. Pick up the pace, or tomorrow I can get a fresh batch of nobodies to do your job. And I’ll make sure you go back to whatever hell you came from. Try me!

Rumour has it that Clyde is in debt to gangsters from down south for whom this is nothing more than a money-laundering operation. Certainly she shows little interest in the food.

Clyde: You melt American cheese on Wonder Bread and these truckers’ll be happy…You know my policy. If it ain’t brown or gray, it can be fried.

The kitchen, however, is the realm of Montrellous (Giles Terera), a wise, spiritual figure who is ‘the John Coltrane of sandwich making.’

Montrellous: Maine lobster, potato roll gently toasted and buttered with roasted garlic, paprika, and cracked pepper with truffle mayo, caramelized fennel, and a sprinkle of…of…dill.

Montrellous has coached his admiring colleagues Letitia (Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjó) and Rafael (Sebastian Orozco) to leave their troubles at the door; to aspire to better things; and to explore the art of sandwich making as a form of self-expression.

Rafael: We speak the truth. Then, let go and cook. Montrellous taught us that. We leave the pain in the pan. We got each other’s backs, and that’s how we get back up.

Letitia: Montrellous is a sensei. Drops garlic aioli like a realness bomb. He knows what we only wish to know.

Between them Clyde and Montrellous represent two poles: cynicism and pessimism versus positivity and hope.

Clyde: Look, I’m not indifferent to suffering. But I don’t do pity. I just don’t. And you know why? Because… dudes like you thrive on it, it’s your energy source, but like fossil fuels it creates pollution. That’s why.

As the play progresses, we learn that each ex-offender is struggling to escape an unfortunate past and a challenging present. Rafael is a recovering drug user who attempted to rob a bank when he was high. He could easily slip back into addiction. Letitia stole medicine for her sick daughter from a pharmacy, and took ‘some Oxy and Addy to sell on the side.’ She continues to contend with childcare pressures and an unreliable ex.

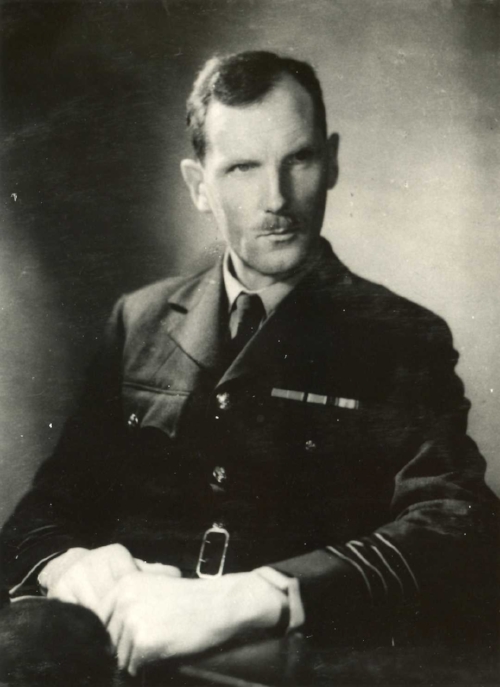

Lynn Nottage

Montrellous: And you know what they say: cuz you left prison don’t mean you outta prison. But, remember, everything we do here is to escape that mentality. This kitchen, these ingredients, these are our tools. We have what we need. So let’s cook.

The camaraderie amongst the kitchen crew is threatened when they are joined by Jason (Patrick Gibson), a felon with a violent record and white supremacist tattoos all over his face. It’s a combustible environment.

Letitia: You here cuz you done run outta options, ain’t nobody gonna hire you except for Clyde.

Gradually we witness how, through industry, truth-telling and mutual support; through learning new skills and raising aspirations, these troubled characters from diverse backgrounds can grow confidence, pride and a sense of identity.

Montrellous: Let whatever you’re feeling become part of your process, not an impediment… This sandwich is my strength. This sandwich is my victory. This sandwich is my freedom.

It would be easy to belittle the central premise of this play. Can you really rebuild lives by means of an obsession with the humble sandwich? Isn’t this all somewhat fanciful? Is the piece taking convenient finger food a little too seriously?

Montrellous: We all make our choices. You never know watcha gonna do when you meet the Devil at the crossroads…But, we ain’t bound by our mistakes.

I spent a whole career selling deodorant, jeans and fried chicken. It’s easy to mock that too. What I observed is that work provides an opportunity to focus on shared beliefs and goals; on building teamwork and purpose; on striving for something better.

In our case, we were seeking to create compelling communication in a 30 second film or 6-sheet poster: emotional product demonstrations. We were on a quest for distilled truth. Absurd perhaps. But I learned that the activity itself doesn’t really matter too much. There is a dignity in labour. We all need something to believe in.

Rafael: Montrellous say the first bite should be an invitation that you can’t refuse, and if you get it right, it’ll transport you to another place, a memory, a desire cuz like everything he touches be sublime.

Eventually the humble truck-stop gets an enthusiastic review in a local newspaper – and Montrellous receives evidence that his endeavours have been worthwhile. He is fortified for a climactic confrontation with Clyde.

Montrellous: No! I won’t destroy the integrity of the sandwich!

In the final exchange, Letitia asks Montrellous if it’s possible to make a perfect sandwich.

Montrellous: Perhaps, or will it just awaken another longing? Let’s see.

‘I read a sign somewhere that said:

‘Everyone walking can always stumble over truth,

But never you mind, because we always get right back up and leave it there.’

Everybody wants to go to Heaven,

But nobody wants to die.

May as well have your Heaven on Earth.

Something to believe,

Something to believe in.

Someone to believe,

Someone to believe in.’

Curtis Mayfield, ‘Something to Believe In’

No. 444