Medea and the Consequences of Love: Should a Company Consider the Victims of Its Success?

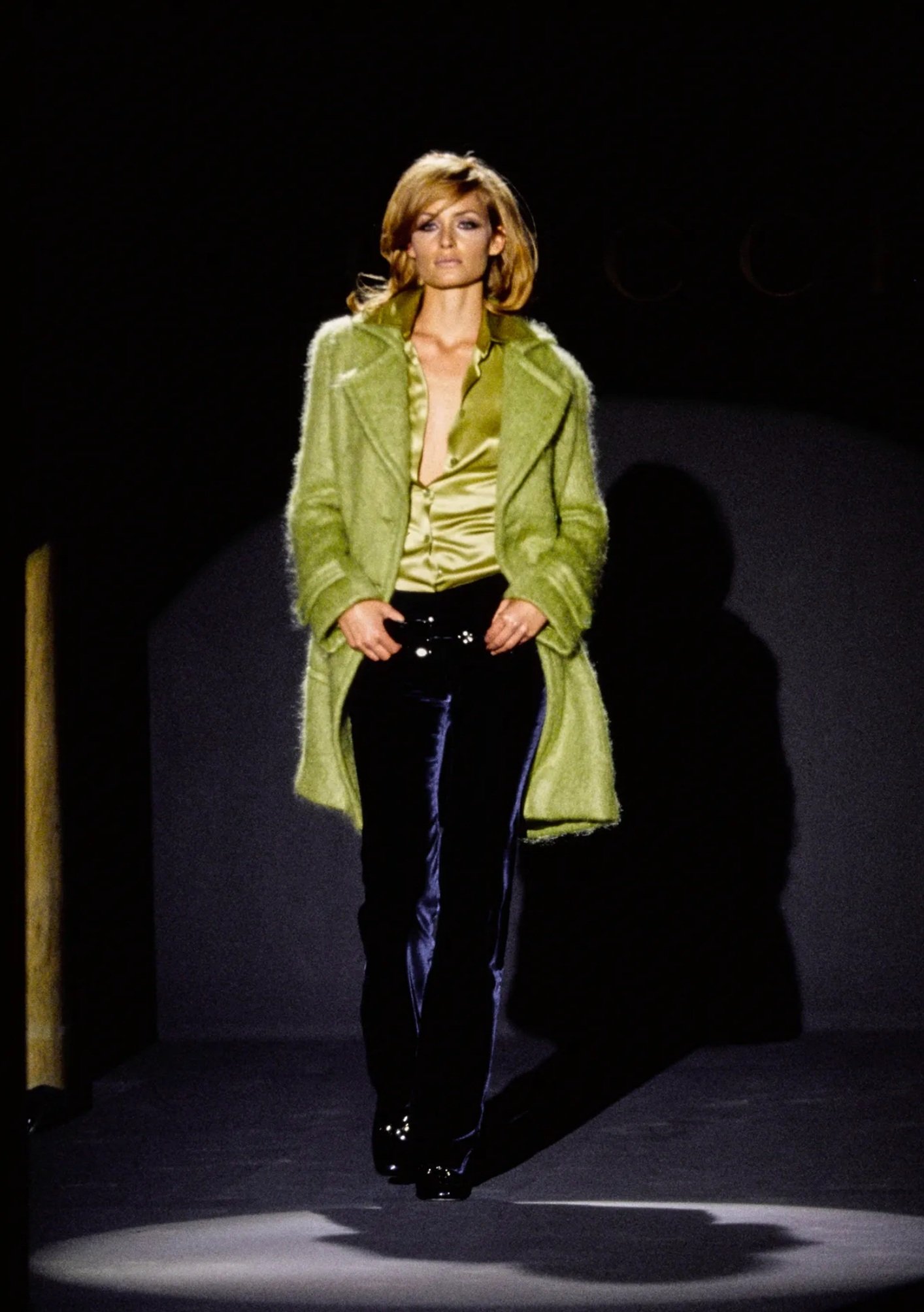

Sophie Okonedo. Photograph: Jane McLeish Kelsey

I recently attended a fine production of Euripides’ ‘Medea’, a Greek tragedy first produced in Athens in 431 BC. (@sohoplace, London until 20 April)

‘I want him crushed, boneless, crawling – I have no choice.’

‘Medea’ is a muscular play that grapples with big themes: betrayal and retribution; xenophopia and feminism; how victims turn to vengeance. It presents us with the dark aspects of heroism and the consequences of love. And in so doing it poses questions about our own attitudes to success.

‘I have done it: because I loathed you more than I loved them.’

Medea ( terrifically played by Sophie Okonedo), a princess of Colchis (in modern-day Georgia) and descended from the gods, has fallen for Greek hero Jason, and used her magic powers to help him steel the Golden Fleece. Now married to Jason and settled with their two sons in Corinth, she discovers that he plans to wed the King’s daughter in order to secure his position there.

‘Her sun is rising, mine going down - I hope

To a red sunset.’

The King, anticipating that Medea will cause trouble, has decreed that she and her children should be exiled. She is overcome with rage, a sense of injustice and a passionate desire for vengeance.

‘Poor misused hand; poor defiled arm; your bones

Are not unshapely. If I could tear off the flesh and be bones; naked bones;

Salt-scoured bones on the shore

At home in Colchis.’

Jason confronts Medea and argues that she only sees one side of the story.

‘I see, Medea

You have been a very careful merchant of benefits. You forget none. You keep a strict reckoning.’

Rather arrogantly, he suggests she is lucky to have been taken from a ‘barbarian’ land to civilised Greece.

‘I carried you

Out of the dirt and superstition of Asiatic Colchis into the rational

Sunlight of Greece, and the marble music of the Greek temples: is that no benefit?’

Jason concludes that Medea has brought all this on herself. She, incandescent with anger, plots her revenge.

‘I’d still be joyful

To know that every bone of your life is broken: you are left helpless, friendless, mateless, childless,

Avoided by gods and men, unclean with awful excess of grief – childless.’

I was quite taken with the way that this play presents the collateral damage that comes in the wake of achievement.

When I was a child, like many people, I first encountered Jason in the 1963 movie epic ‘Jason and the Argonauts’ (featuring the extraordinary stop-motion animation of Ray Harryhausen). This cinematic Jason is brave, ingenious, romantic. He is a luminous hero.

Euripides gives us Jason’s sinister side. He comes across as disloyal and egotistical; bigoted and sexist.

‘A man dares things, you know; he makes his adventure

In the cold eye of death; and if the gods care for him

They appoint an instrument to save him; if not he dies.

You were that instrument.’

The play asks us to consider the victims of Jason’s heroic journey. He has been on a quest for glory and power. But he leaves behind him a trail of death and destruction; of broken hearts and lives.

‘Not justice; vengeance.

You have suffered evil, you wish to inflict evil.’

For Euripides heroism comes at a cost; success creates victims and victims demand vengeance. There’s a price to pay for love.

‘A great love is a fire

That burns the beams of the roof.

The doorposts are flaming and the house falls.

A great love is a lion in the cattle-pen,

The herd goes mad, the heifers run bawling

And the claws are in their flanks.

Too much love is an armed robber in the treasury.

He has killed the guards and he walks in blood.’

This may seem strange, but as I sat in the theatre, I found myself wondering about the world of work.

In commerce we like to celebrate success. We tell tales of battles fought and victories won. We make heroes of our top performers. But how often do we stop to consider the colleagues who don’t quite attain the highest levels; the collateral damage of our leaders’ high standards and impossible demands; the victims of success?

A progressive, modern business should be mindful of the failings of its triumphant talent; should strive to ensure that no one is left behind in the advance; should keep an eye on maintaining a coherent culture, even when everything’s going well and to plan. Because a unified culture can sustain you through the tough times that will inevitably follow.

‘It is dangerous to dream of wine; it is worse

To speak of wailing or blood:

For the images that the mind makes

Have a way out, they work into life.’

As a society we imagine that we have only attended to the issues relating to mental health in the last century, and only taken them seriously in the last decade. And yet in the 5th century BC, Euripedes was well aware of the psychological pressure Medea is under as she builds ‘that terrible acropolis of deadly thoughts.’

Indeed the Chorus recommends that some respite be attained by getting out more, by sharing problems – by embracing a ‘talking cure.’

‘We Greeks believe that solitude is very dangerous, great passions grow into monsters

In the dark of the mind; but if you share them with loving friends they remain human, they can be endured.’

This is sound advice, and perhaps the first step to avoiding seething jealousies in the workplace. We may also heed Euripides’ encouragement to nip prospective problems in the bud.

‘To annihilate the past -

Is not possible: but its fruit in the present -

Can be nipped off.’

I left this production of ‘Medea’ inspired by the compelling performances and timeless themes; by the relevant issues and rich language (an excellent translation by Robinson Jeffers from the 1940s). And I left relieved not to have been born into the aristocracy.

‘Oh it’s a bad thing

To be born of high race, and brought up wilful and powerful in a great house, unruled.

And ruling many: for then if misfortune comes it is unendurable, it drives you mad. I say that poor people

Are happier: the little commoners and humble people, the poor in spirit: they can lie low

Under the wind and live: while the tall oaks and cloud-raking mountain pines go mad in the storm,

Writhe, groan and crash.’

'Now you say you're lonely,

You cry the long night through.

Well, you can cry me a river,

Cry me a river.

I cried a river over you.

Now you say you're sorry

For being so untrue.

Well, you can cry me a river,

Cry me a river.

I cried a river over you.

You drove me, nearly drove me

Out of my head,

While you never shed a tear.

Remember, I remember

All that you said.

Told me love was too plebeian.

Told me you were through with me,

And now you say you love me.

Well, just to prove you do

Come on and cry me a river,

Cry me a river,

I cried a river over you.’

Julie London,’Cry Me a River' (A Hamilton)

No. 411