The Textile Sculptures of Magdalena Abakanowicz: ‘We Find Out About Ourselves Only When We Take Risks’

Magdalena Abakanowicz, 1960s, photo artist’s archive

'Art does not solve problems, but makes us aware of their existence. It opens our eyes to see and our brain to imagine.'

Magdalena Abakanowicz

I recently attended an excellent exhibition of the work of Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz. (Tate Modern, London until 21 May 2023)

In the 1960s and ‘70s Abakanowicz took tapestries from the wall into three-dimensional space. She made sculptures that were organic, soft and fibrous. And she employed traditional craft skills in the service of high art. Her huge haunting textiles bring to mind vibrant plant life and mysterious foliage; rippling garments and pulsing body parts. These are enchanted environments.

Abakanowicz teaches us that, in whatever field we’re working, we can always rewrite the rules.

'It is easy to follow, but it is uninteresting to do easy things. We find out about ourselves only when we take risks, when we challenge and question.'

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakan.

Photo credit D. Cummings-Palmer

Abakanowicz was born in 1930 into an aristocratic family in rural central Poland. Her early years were overshadowed by the Polish-Soviet War, by Nazi occupation and then by Communist rule. She studied at the Academy of Plastic Arts in Warsaw and began her career painting large biomorphic designs on fabric. But her real interest was in weaving.

‘I am interested in constructing an environment from my forms.

I am interested in the scale of tensions that arises between various shapes which I place in space.

I am interested in the feeling when confronted by the woven object.

I am interested in the motion and waving of the woven surfaces.

I am interested in every tangle of thread and rope and every possibility of transformation.

I am interested in the path of a single thread.

I am not interested in the practical usefulness of my work.’

Abakanowicz was naturally independent minded. From the outset her tapestries dispensed with preparatory designs or templates (‘cartoons’). Rather she improvised on the loom, creating colourful, fluid, abstract shapes, switching between materials with remarkable dexterity - from sisal to wool to horsehair.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakan.

Photo credit D. Cummings-Palmer

In the mid-1960s she discarded the rectangular format of traditional tapestry. Instead she hung curved fabric forms freely in space. The burnt umber sculptures she created at this time suggest cocoons, shells and insects; a beguiling journey into the forests of her childhood.

‘Strange powers dwelled in the woods and lakes that belonged to my parents. Apparitions and inexplicable forces had their laws and their spaces.’

Abakanowicz went further still. She took to arranging her fabric sculptures - or what an art critic dubbed ‘Abakans’ - in specially lit clusters, so that they cast compelling shadows and could be in dialogue with each other. She sought to create immersive ‘situations’ or ‘environments’, places to explore and hide.

‘The Abakans were my escape from categories in art. They could not be classified. Larger than me, they were safe like the hollow trunk of the old willow I could enter as a child in search of hidden secrets.’

Abakanowicz employed industrially woven cloth, rope, hemp, burlap, flax and found material. Sometimes her work seems like tall trees or vines; sometimes like strange boulders or pods; sometimes like huge heads or interior organs. You can walk among them, as if through a magical forest or a mysterious alien landscape. There is a sense of comforting softness; of germination and budding; of brooding silence.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakan.

Photo credit D. Cummings-Palmer

‘I see fibre as the basic element constructing the organic world on our planet. It is from fibre that all living organisms are built, the tissue of plants, leaves and ourselves… our nerves, our genetic code, the canals of our veins, our muscles… We are fibrous structures.’

In the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s Abakanowicz went on to create humanoid sculptures and outdoor installations, working with metal, wood, stone and clay. All the while she continued to explore humanity’s relationship with nature. She passed away in 2017 at the age of 86.

So often in life and business we are boxed in by convention and tradition. We feel obliged to follow the crowd along the beaten path.

Abakanowicz, the weaver of sculptures, teaches us to deny hierarchies; to transgress rules; to see opportunity everywhere.

‘I like neither rules nor instructions, these enemies of the imagination. I make use of the technique of weaving by adapting it to my own ideas.’

'So tonight, gotta leave that nine to five upon the shelf,

And just enjoy yourself.

Groove.

Let the madness in the music get to you.

Life ain't so bad at all,

If you live it off the wall.

Life ain't so bad at all.

Live your life off the wall.'

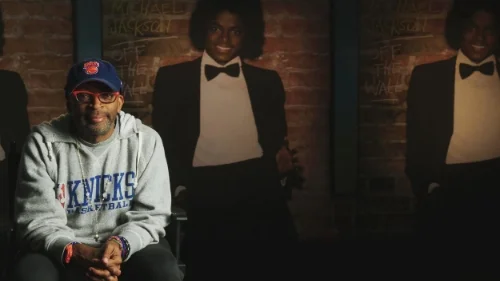

Michael Jackson, ‘Off the Wall’ (R Temperton)

No 403