MC Escher: 'Only Those Who Attempt the Absurd will Achieve the Impossible’

'We adore chaos because we love to produce order.'

MC Escher

I recently watched a film documenting the life and work of Dutch graphic artist MC Escher (2018’s ‘Journey to Infinity’ by Robin Lutz).

‘I don’t belong anywhere any more…I hover between mathematics and art.’

Through his drawings, lithographs and woodcuts, Escher prompted us to reflect on perspective and perception; dreams and reality; order and chaos. Through his mesmerising tessellations and fantastical landscapes; impossible objects and implausible architecture, he bridged the divide between art and mathematics. His was a playful world of visual paradox, magical metamorphoses and infinite possibility. He cultivated a sense of wonder.

'Wonder is the salt of the earth. Originality is merely an illusion.’

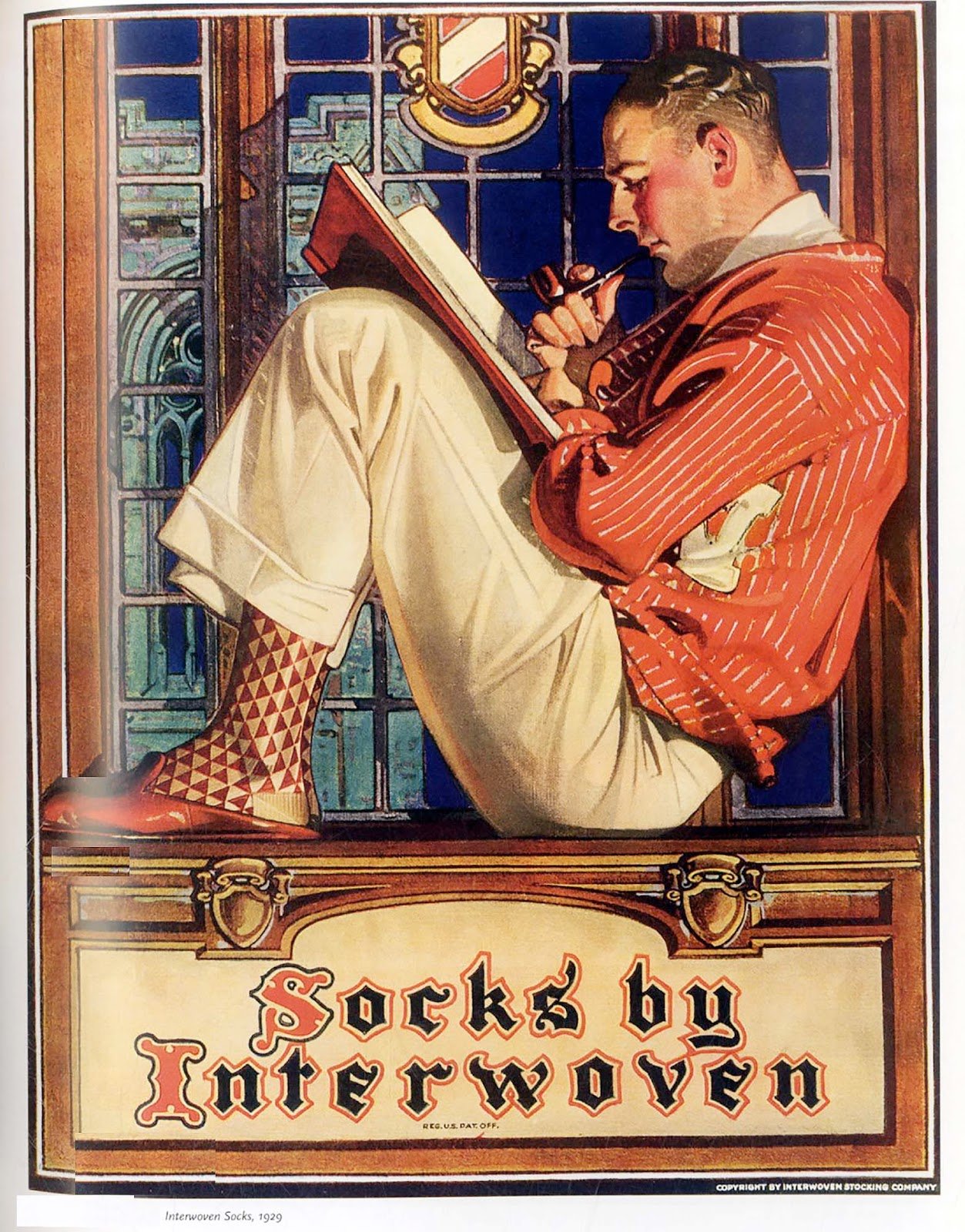

M. C. Escher tessellation

1. ‘Enjoy the Tiniest Details’.

In 1898 Maurits Escher was born into a wealthy family in Leeuwarden, the Netherlands. He was a sickly child and struggled at school. But he was always good at drawing.

‘The only bright spots are the drawing lessons. Not because I am any good at it, but because it’s my only comfort during this awful time.’

Escher attended the Haarlem School of Architecture and Decorative Arts. Still suffering from weak health, in 1922 he set off on a recuperative trip through Italy, visiting Tuscany and the Amalfi Coast. It seemed to do him some good.

‘I cannot describe the curious feeling this lovely beauty gives me. My poor eyes are straining and my poor brain is trying to comprehend the incomprehensible. Rarely if ever have I felt so calm, pleasant and comfortable than lately.’

In Italy Escher created richly detailed drawings of hilltop towns and seaside communities; houses clustering around imposing churches; monasteries nestling alongside monumental mountain rocks.

On his travels Escher also met Jetta Umiker, whom he married in 1924.

‘She exerts an influence on me similar to that of an electromagnet on a scrappy piece of cast iron.’

The young couple settled in Rome from where Escher continued to make study trips. He was beguiled by the beautiful intricacies of nature.

‘I want to learn to look and see better whilst I am drawing. I want to enjoy the tiniest details…With your nose right on top of [a small plant] you see all of its beauty and all of its simplicity. But when you start drawing only then do you realise how terribly complicated and shapeless that beauty really is.’

2. Be Open to Inspiration

Escher travelled to Spain where he was particularly inspired by the fourteenth-century Alhambra palace in Granada. He was fascinated by the Moorish architecture, the intricate decorative designs on the walls and ceilings, the coloured tiles with their infinite variety of geometric patterns.

‘What fascinates me in the tiles of the Alhambra is the discovery of a motif that repeats itself according to a certain system.’

Escher determined that Moorish tessellation could provide the basis for a new direction for his art. But, in contrast with the designs he had studied at the Alhambra, his would accommodate wildlife.

‘What a pity the Moors didn’t use figures derived from nature.’

Starting with a series of geometric grids, Escher created complex configurations of interlocking birds and butterflies; intertwining fish and reptiles; intersecting lizards in red, green and white. His work explored the mesmeric effects of pattern and repetition, the relationship between space and time.

‘I began to see the possibilities offered by the regular division of the plane. For the first time I dared to create compositions based on the problem of expressing endlessness within a limited plane.’

3. Follow your Passion No Matter What Others May Think

Escher was increasingly drawn to think of his art in mathematical terms. In this respect he felt a fellowship with Bach.

‘I am smitten by Bach’s music. A short motif that repeats itself in various ways – identically in a different key, back to front or upside down. They’re almost mathematical figures.’

Escher pressed on in pursuit of his passion, even though he was unsure whether what he was creating was art at all.

‘The mathematical interest is becoming so dominant that I am wondering whether it is still trying to be art and whether it even belongs in an art exhibition.’

Escher’s colleagues and companions were not impressed with his new direction.

‘Deeply saddening and hangover-inducing remains the fact that I’m starting to speak a language that is understood by very few people.’

4. Cultivate a Sense of Wonder

Gradually the political climate in Italy under Mussolini became more toxic. In 1935, when his nine-year-old son was obliged to wear a military uniform to school, Escher moved his family to Switzerland. Later they decamped to Brussels and finally, in 1941, they settled in Baarn, the Netherlands.

'What I give form to in daylight is only one per cent of what I have seen in darkness.'

As the Second World War closed in around them, Escher focused single-mindedly on his work. His designs became more and more inventive. Drawing on childhood games of word association, he let his imagination run free.

'My work is a game, a very serious game.'

A river flows from day to night. A flock of black birds emerge magically from white fields, while white birds flying in the opposite direction appear mysteriously from dark farmland. Reptiles rise up from a two-dimensional picture, crawling across a series of three-dimensional objects before re-entering the picture once more. A waterfall is in perpetual motion. Two faces are formed from one continuous ribbon. A hand draws itself. An endless series of faceless figures rush downstairs, passing a continuous stream of characters running upstairs at different angles.

Day and Night (1938)

'Are you really sure that a floor can't also be a ceiling?'

Escher created magical, slightly disturbing worlds that prompt us to question our notions of reality and illusion, order and chaos. He was driven by a sense of wonder.

'He who wonders discovers that this in itself is wonderful.'

5. Be Your Hardest Taskmaster and Your Harshest Critic

Of course, although Escher’s work was playful and imaginative, it required an innate gift for mathematics and a phenomenal eye for detail.

‘It is really only a matter of dogged persistence and continuous pitiless self criticism.’

Escher was motivated by a fierce desire to attempt the impossible.

‘Any schoolboy with a little aptitude will perhaps be better at drawing than I am. But what he most often lacks is the tough yearning for realisation, the teeth-grinding stubbornness, and saying: even though I know I cannot do it, I want to do it anyway.’

6. Pursue a Vision that Cannot Be Realised

In the 1960s Escher was surprised to find his work enthusiastically adopted by the counterculture in the west coast of the United States.

‘What on earth does this young generation see in my work? Doesn’t it lack all the qualities that are hip these days? It is cerebral and rationalised instead of wild and sexy. And how can they reconcile it with their addiction to narcotics?’

So Escher wasn’t impressed when Mick Jagger asked for an image to use on an album cover.

‘Please tell Mr Jagger that I am not Maurits to him, but, very sincerely, MC Escher.’

In 1969 Escher finished his last woodcut, ‘Snakes’, in which three serpents wind through a pattern of linked rings that shrink to infinity. He died in a hospital in Hilversum in 1972, aged 73.

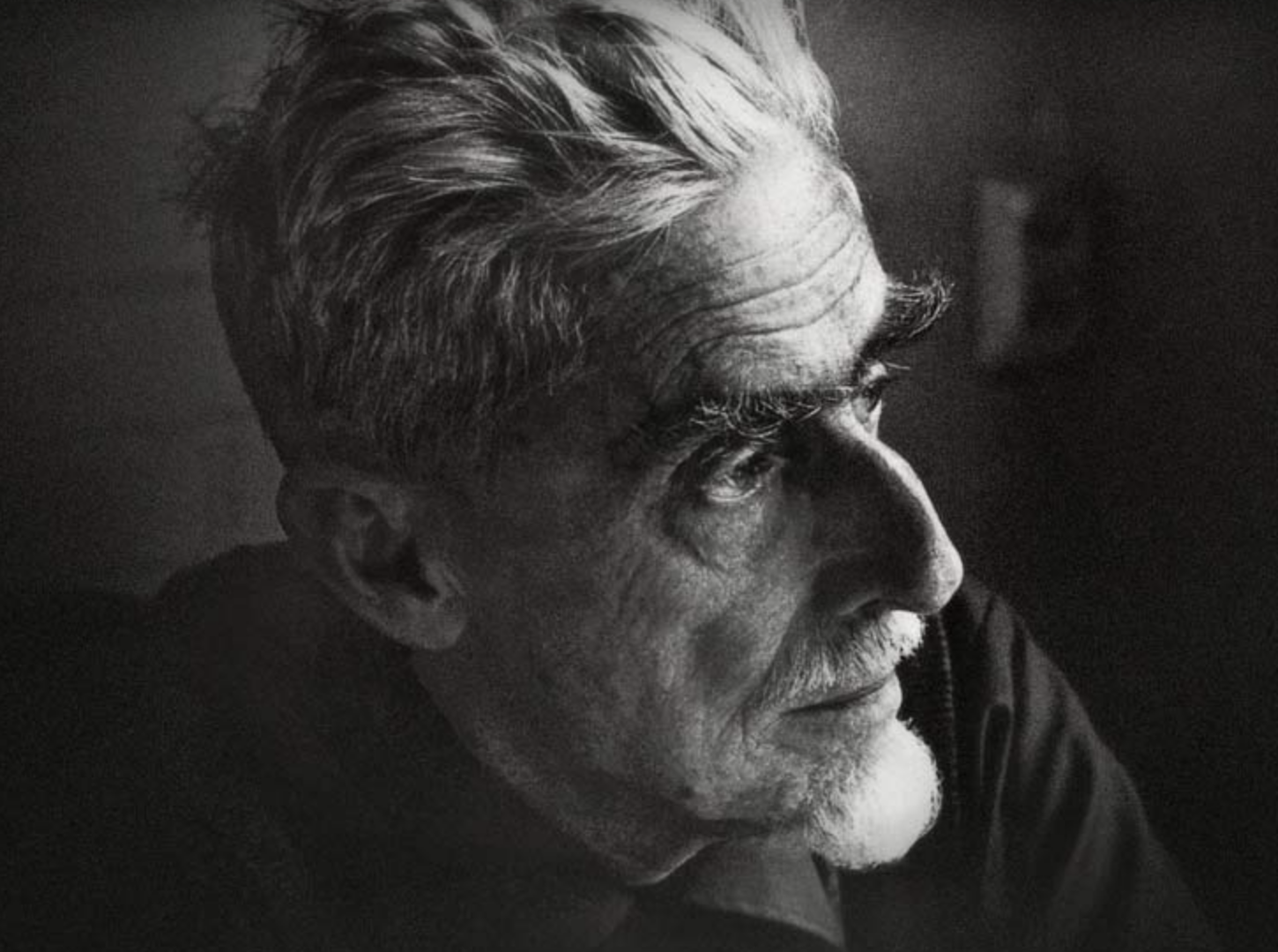

Portrait of M.C. Escher by Nikki Arai

'Only those who attempt the absurd will achieve the impossible…. I think it's in my basement... Let me go upstairs and check.’

Escher’s designs should resonate with people in the business of brands and communication. We too work with pattern, rhythm and repetition, bridging the fields of art and mathematics, endeavouring to create a sense of wonder in our audiences. We would do well to embrace something of Escher’s dogged persistence, his childlike playfulness and his relentless quest for the impossible.

‘I always pursue a vision that cannot be realised.’

'As around the sun the earth knows she's revolving,

And the rosebuds know to bloom in early May.

Just as hate knows love's the cure,

You can rest your mind assure,

That I'll be loving you always.’

Stevie Wonder, ‘As'

No. 372