Blood Memories: Alvin Ailey’s Emotional Embrace

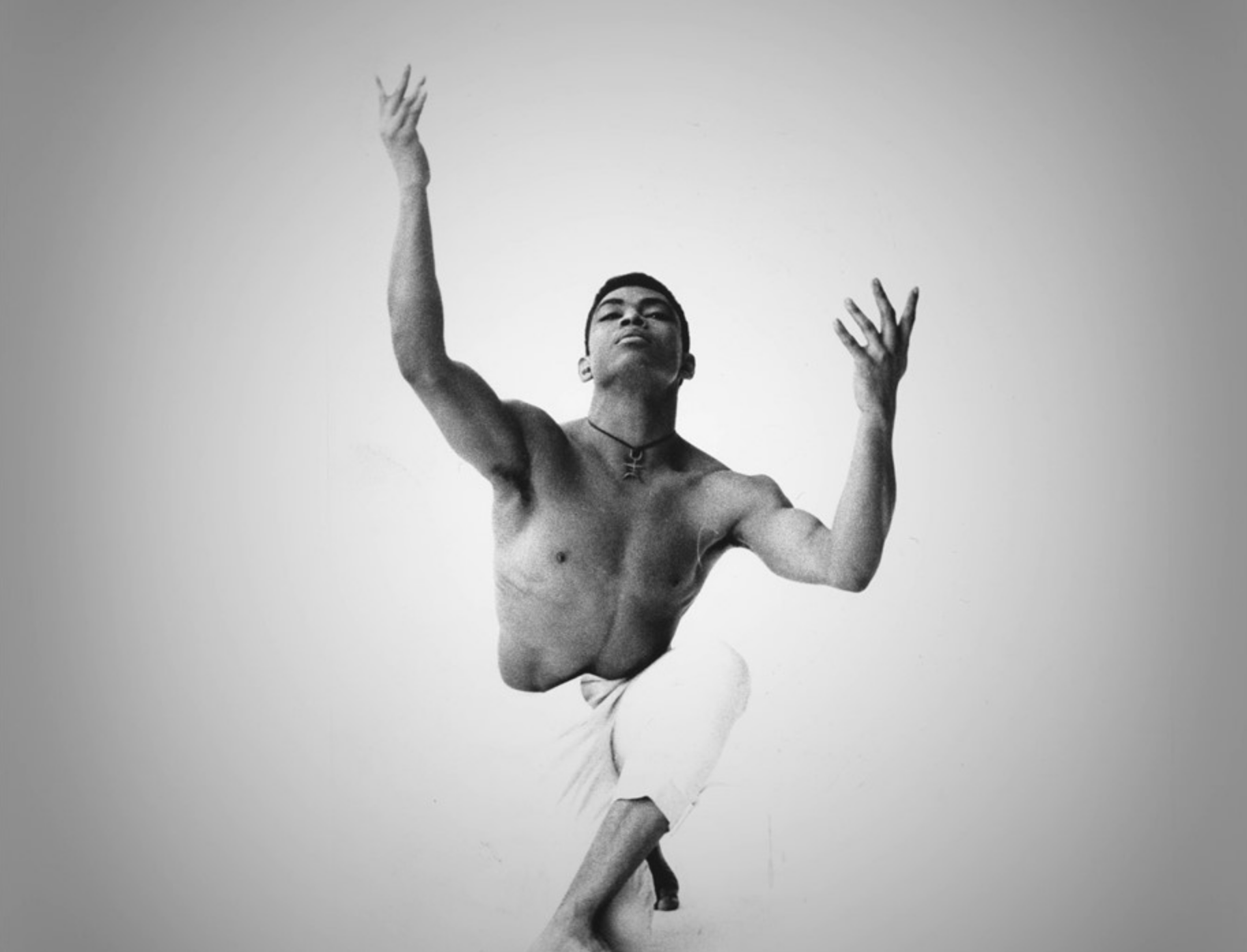

Alvin Ailey. Photo: Norman Maxon, New York Public Library

'I’m Alvin Ailey. I’m a choreographer. I create movement and I’m searching for truth in movement.'

I recently watched a fine film documenting the life and work of choreographer Alvin Ailey. (‘Ailey’ directed by Jamila Wignot, 2021)

'I wanted to explore Black culture, and I wanted that culture to be a revelation.’

Ailey was an innovative dance maker who channelled his own experience onto the stage. He founded a company that celebrated African American culture and produced performances that resonated with audiences all over the world. His work was heartfelt, dramatic and supremely lyrical. Where the traditional ballet world could be cold, cerebral and rarefied, here was dance that was warm, physical and sensual - created around what most of us today would recognise as dance music.

‘As choreographers we start with an empty space and a body or two, and we say ‘Carve this space.’ I love creating something where there was nothing before.’

There’s a great deal we can learn from this visionary man.

1. ‘Justify Your Steps’

Born in Rogers, Texas in 1931, Ailey was raised by his mother, who moved from town to town looking for work in the cotton fields or in domestic service.

‘Texas was a tough place to be. I mean if you were Black you were nothing.’

When Ailey was 12 they moved to Los Angeles where he had his first taste of dance on stage, seeing performances by the Ballet Russe of Monte Carlo and by the African American pioneer Katherine Dunham.

Ailey studied dance under Lester Horton whose company was one of the first racially integrated troupes in the United States.

‘Lester taught us to justify movement. Not just to do a step, but to feel something about the step. Not just to do a plie, but to give it some kind of emotion.’

After Horton’s death in 1953, Ailey took on the role of company director and began to choreograph his own work. He also performed in a number of Broadway shows.

2. Find ‘Release’

At that time opportunities for Black dancers and artists were occasional and marginal.

‘You were very specially a guest artist there. You could move into this neighbourhood for a minute. But after you’ve finished doing your gig, please move out.’

Judith Jamison, Dancer

Ailey resolved to establish his own company, one that would celebrate the African-American experience and at the same time provide secure work for Black performers.

'I always felt that that dance was a natural part of what I wanted to express, that what I can do with my body was a part, a very important part, of me, and a way to release some of those things in myself that I had been looking for.’

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in a 2018 performance of "Revelations," at New York City Center.

Photo: Andrea Mohin/The New York Times

3. Draw on Your ‘Blood Memories’

In 1958 Ailey founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and set about creating dance to the music of spirituals, gospel and blues; conveying movement and imagery recollected from church, house parties and roadside honky-tonks. Two years later these ‘blood memories’ formed the basis of his most iconic work: ‘Revelations.’

'I came up with a piece. A saga to the Black experience. I would call it ‘Revelations’. . . My blood memories. The memories of my parents, uncles and aunts. Blues and gospel songs that I knew from Texas.’

Spinning, striding, swooning and swaying; hands outstretched, lowered to the soil and reaching for the sky. The dancers are torn between joy and pain, suffering and salvation. In long white robes they process to church, holding their parasols up high. Hands on hips, backs arched, heads to heaven. They wade in the water; run to save their souls; settle down on stools to talk at sunset, in canary coloured gowns and hats, fans fluttering.

'I've been 'buked and I've been scorned

Tryin' to make this journey all alone.

You may talk about me sure as you please.

Your talk will never drive me down to my knees.’

Mahalia Jackson, ‘I’ve Been Buked’

4. Dramatise Universal Themes

While Ailey articulated his community’s values and experiences in his work, he also sought to explore universal themes and to be broadly entertaining. His ballets addressed love and loss, the trials of being an artist, the tribulations of being a mother, the death of a friend.

'I wanted to do the kind of dance that could be done for the man on the streets, the people. I wanted to show Black people that they could come down to these concert halls. That it was part of their culture being done there. And that it was universal.'

A still from Ailey. ‘He’s a public figure, who can’t live out all of himself in public.’ Photograph: Neon

5. If You Want to Say Something, You’ve First Got To Get the Audience’s Attention

In the 1960s the US State Department sponsored AAADT's international tours to Asia, Africa, Europe and Russia. Performances broadcast on Moscow television were seen by over 22 million viewers. By the start of the 1970s the troupe had established a reputation at home and abroad. And in 1972 it became a resident company of New York City Center.

Ailey was keen to convey his concerns about civil rights and social injustice. He believed that a message first needs an audience.

‘In order to say something to an audience you’ve got to get them to look at you and listen to you. So if I’m trying to make a protest statement, the audience is much more likely to get that message if they can hear something like ‘House of the Rising Sun.''

Ailey’s 1969 piece ‘Masekela Language’ was prompted by the assassination of Black Panther activist Fred Hampton. In one scene a group of dancers cradle a dead man, as a voice addresses the audience, repeating over and over: ‘Thank you very much, ladies and gentlemen.’

6. Wrap Your Colleagues in an ‘Emotional Embrace’

Ailey had a robust commitment to excellence and a fierce passion to realise his vision. He could be a hard taskmaster. But he also established a deep supportive rapport with his dancers. He wrapped them in an emotional embrace.

‘If he was talking to you from 50 feet away you would feel that embrace. You would feel that comfort in knowing you could make an absolute fool of yourself. You would feel safe to extend yourself enough so that you felt free.’

Judith Jamison, Dancer

7. ‘You Have to Be Possessed’

Ailey regarded dance as a vocation and he was well aware that it came at a price.

‘Dance, it’s an enormous sacrifice. I mean, it’s a physical sacrifice, dancing hurts. You don’t make that much money. . . It’s a tough thing, you know, you have to be possessed to do dance.'

Ailey was a private man. He felt unable to speak publicly about being gay and he had trouble developing relationships. He also put himself under intense pressure to sustain the company’s finances and to keep producing new and innovative work.

'We still spend more time chasing funds than we do in the studio in creative work.'

'No matter what you write or choreograph, you feel it's not enough.’

'Sometimes you feel bad about yourself when there's no reason to.’

In 1980, isolated and exhausted, Ailey suffered a breakdown. He was later found to have been suffering from bipolar disorder.

‘The agony of coming from where I came from and then dancing on the Champs Elysee. The contrast of all that. On one hand, the darkness where you feel like you are just nobody, nothing. And the other hand, you are the king, you’re on top of the world.'

Alvin Ailey Dance Theater in the "Move, Members, Move" section of Revelations, in 2011.Earl Gibson/AP

8. ‘Don’t Be Put in a Bag’

Ailey recovered and returned to the company, transferring day-to-day management to his protégé Judith Jamison. He carried on producing work and sought increasingly to break from the constraints imposed on him by the expectations of critics and audiences.

'The problem is, if you’re a Black anything in this country, people want to put you into a bag. People sometimes say, ‘Well, you know, why is he doing that now, why can’t he stick to the blues and the spirituals?’ And I’m also a 20th century American, and I respond to Bach, and Ellington, and Benjamin Britten, and Samuel Barber, and why shouldn’t I?’

9. Make It Easier for the Next Generation

'I wanna be ready.

I wanna be ready.

Ready to put on my long, white robe.'

‘I Wanna Be Ready’

In 1989 Ailey died from an AIDS-related illness. He was 58.

Ailey was a pioneer who had his eyes on the horizon. As well as creating more than 100 ballets, he ensured that his company performed pieces by other choreographers so that its future would be secure without him. Following his death, Jamison took over as artistic director and the AAADT went from strength to strength. Ailey had always wanted to make it easier for the next generation. His aim was true.

‘To provide a place of beauty and excitement, a place for other choreographers to experiment. To provide a place where people can come and feel like they can add themselves and then reap the benefits of what they put in. I want it to be easier than it was for me.’

'I wanna go where the north wind blows.

I wanna know what the falcon knows.

I wanna go where the wild goose goes.

High flying bird, high flying bird, fly on...

I want the clouds over my head.

I don't want no store bought bed.

I'm gonna live until I'm dead.

Mother, mother, mother, mother save your child.

Right on, be free.’

Voices of East Harlem, ‘Right On, Be Free’ (C Griffin)

No. 375