Dancing at Lughnasa: When ‘Atmosphere Is More Real than Incident’

From left, Bláithín Mac Gabhann, Alison Oliver, Louisa Harland and Siobhán McSweeney in ‘Dancing at Lughnasa’ © Johan Persson

‘Look at yourselves, will you! Just look at yourselves! Dancing at our time of day? That’s for young people with no duties and no responsibilities and nothing in their heads but pleasure.’

I recently saw an excellent production of Brian Friel’s 1990 work ‘Dancing at Lughnasa.’ (The National Theatre, London until 27 May.)

This ‘memory play’ is shot through with nostalgia and wistfulness. It asks us to consider how we reconstruct our own past; and how our recollections are as much forged from atmosphere as incident.

A middle-aged man Michael Evans recalls the summer of 1936 when he was a young boy living with his unmarried mother and four spinster aunts in rural Donegal.

Oldest sister Kate, a teacher and the only wage earner in the house, is prim, devout and worried about how to make ends meet. Joker Maggie sings popular songs, tells riddles and smokes Woodbines. Chris, Michael’s mother, is dreamy, romantic and prone to depression. Quiet, thoughtful Agnes, in wraparound apron, takes particular care of wellington-booted, ‘simple’ Rose.

‘When are we going to get a decent mirror to see ourselves in?’

‘You can see enough to do you.’

‘Steady on, girl. Today it’s lipstick; tomorrow it’s the gin bottle.’

The sisters babble, bicker and bake soda bread on the large iron range. They tend to their pet white rooster, fetch turf and pick bilberries by the old quarry. They reflect on old friends and missed opportunities; on family secrets and whether to attend the forthcoming harvest dance.

Justine Mitchell & Siobhán McSweeney. Photo by Johan Persson

‘This must be kept in the family, Maggie! Not a word of this must go outside these walls – d’you hear? – not a syllable!’

Humour, discipline, determination and faith sustain them through what are clearly tough times. Their world is on the cusp of change. The school plans to lay off Kate due to falling rolls, and a new factory seems likely to deprive the two younger siblings of the little money they earn knitting gloves at home. Even the civil war in faraway Spain threatens to impact on their lives.

‘Even though I was only a child of seven at the time I know I had a sense of unease, some awareness of a widening breach between what seemed to be and what was, of things changing too quickly before my eyes, of becoming what they ought not to be.’

Through it all the women lift their spirits by dancing to their unreliable wireless (fondly referred to as Marconi). To the fast heavy beat of a ceili band, one by one they break into a jig. Knitting dropped, feet stomping, arms, legs and hair flying - they sing and shout and spin and turn. It’s a wondrous sight of wild, raucous, almost pagan, abandon.

‘I had witnessed Marconi’s voodoo derange those kind, sensible women and transform them into shrieking strangers.’

‘Oh play to me, Gypsy, the moon's high above,

Oh, play me your serenade, the song I love.

Oh sing to me, Gypsy, and when you are gone,

Your song will be haunting me and lingering on.’

Gracie Fields, ‘Play to Me, Gypsy’ (K Vacek / J Kennedy)

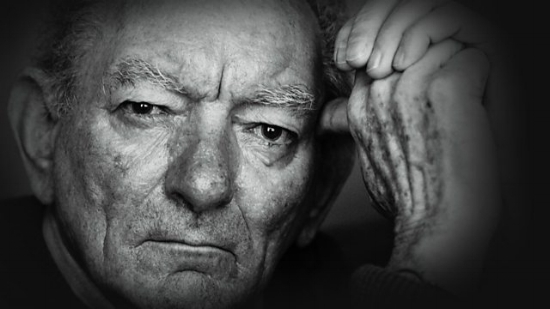

Brian Friel. Image courtesy of RTÉ

Friel was in his early sixties when he wrote ‘Dancing at Lughnasa’. It was based quite closely on his own upbringing. What’s striking about the play is that not too much happens. The sisters have to tend to their brother, who has returned from missionary work in Uganda suffering from mental illness. Chris must navigate occasional visits from Michael’s charming but feckless father. And Rose goes walkabout. In a concluding speech Friel explains that his recollection of this distant time is constructed more from mood than particular events.

'There is one memory of that Lughnasa time that visits me most often; and what fascinates me about that memory is that it owes nothing to fact. In that memory atmosphere is more real than incident and everything is simultaneously actual and illusory.'

In the communications business we, quite appropriately, spend a good deal of time constructing narratives. Stories are powerful vehicles for messages; for conveying features, benefits and rewards. But do we sufficiently attend to atmosphere – to the mood, spirit and feelings that we wish our brands to express? Surely atmosphere provides the fabric for enduring recollections.

As ‘Dancing at Lughnasa’ demonstrates, you can convey a great deal without recourse to specific incidents, actions or narratives – and sometimes without using words at all.

'When I remember it, I think of it as dancing. Dancing with eyes half closed because to open them would break the spell. Dancing as if language had surrendered to movement – as if this ritual, this wordless ceremony, was now the way to speak, to whisper private and sacred things, to be in touch with some otherness. Dancing as if the very heart of life and all its hopes might be found in those assuaging notes and those hushed rhythms and in those silent and hypnotic movements. Dancing as if language no longer existed because words were no longer necessary…'

'Twas on the Isle of Capri that he found her

Beneath the shade of an old walnut tree.

Oh, I can still see the flowers blooming round her

When they met on the Isle of Capri.

She was as sweet as the rose at the dawning

But somehow fate hadn't meant it to be,

And though he sailed with the tide in the morning,

Yet his heart's on the Isle of Capri.’

Gracie Fields, 'Isle of Capri’ (J Kennedy / W Grosz)

No. 419