501! Contemporary Lessons from a Vintage Case Study

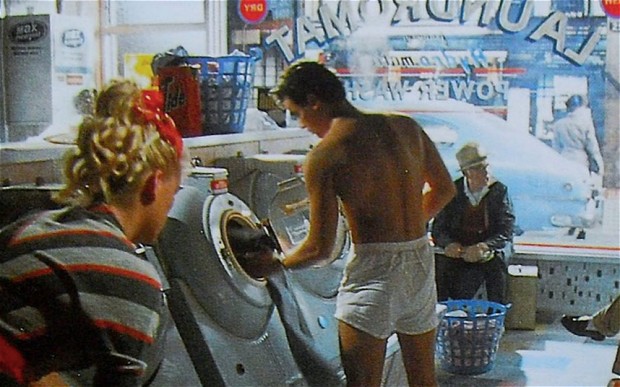

Levis Ad - BBH

During my twenty-five years in advertising, I worked on all manner of client businesses. From banks and beers, to fried chicken and phone networks. Without doubt the experiences that left the deepest impression, and had the biggest impact on my career, were those that I gained on the Levi’s jeans account in the 1990s.

Between 1985 and 1998 Levi’s campaign for its 501 jeans, developed by its agency BBH, was one of the most awarded and admired in the advertising world. It created a mythical America of enigmatic, unspeaking heroes; of youthful adventure on the open road; of effortless style and heart-rending tunes. And it sold a great many pairs of jeans.

Let’s take a step back in time to see if this vintage case study suggests any lessons that might still be relevant today.

‘Be Yourself. Everyone else is already taken.’

Oscar Wilde

At the heart of the Levi’s 501 story was the determination that it should be true to itself.

Levi’s 501 was the original denim jean. It was designed in 1873 for miners in the California Gold Rush. Its riveted construction, button fly and XX stitching sustained it through tough manual tasks. Its rudimentary ‘anti-fit’ cut was appropriate to its modest origins. It was the jean that was adopted in the ‘50s by the likes of Marlon Brando, James Dean and Eddie Cochrane, and thereby became a badge of youth rebellion. It had a unique heritage to be proud of.

However, when in 1985 Levi’s struggling UK organisation submitted the 501 to consumer testing with a view to a possible re-launch, the results were not encouraging. Modern British consumers were more accustomed to zip flies and figure-hugging fits. The Levi’s brand was perceived as middle-aged and middle-of-the-road. What’s more, Levi’s was quintessentially American at a time when UK youth culture was not looking across the pond for inspiration.

The sensible decision might have been to back away. Or at least to launch a style more in keeping with contemporary tastes.

But Levi’s and BBH were determined. This was the original and definitive jean, the blueprint for everything that followed. It was a design classic. It deserved a hearing.

Fanning the Flames of Discovery

There was a glimmer of encouragement. A small group of cognoscenti in the fashion, music and film industries had already fallen for the 501’s authenticity and unique design. There was a growing interest in retro ‘50s culture, and a thriving second-hand market in 501s from the States. Perhaps, by reflecting what these enthusiasts loved so much about the product, there was an opportunity to fan the flames of discovery.

A Simple Story Stylishly Told

A young man walks into a laundrette to the sound of ‘I Heard It Through the Grapevine.’ He removes his jeans and t-shirt and puts them in the washer with some stones. He sits down to read a magazine in his boxer shorts and socks, as others look on in amazement.

With a 1985 TV commercial conveying this modest narrative, Levi’s 501 jeans were introduced to the mass British public. Despite its seeming simplicity, ‘Laundrette’ was an immediate cultural and commercial hit. It was discussed in national media. The music entered the charts. Nick Kamen, the actor playing the central character, became an overnight celebrity. Boxer shorts were suddenly fashionable, with two million pairs being bought in 1986 alone. And 501 jeans sold so quickly that demand outstripped supply.

There followed a series of similarly iconic commercials, all depicting youthful heroes in pursuit of their own American dream, equipped with little more than their 501s, a white t-shirt and an innate resourcefulness. Within three years of the re-launch, 501 sales had increased twenty-fold - at a premium price of between £27 and £30, in a market where the norm was sub-£20.

Levi’s succeeded because it didn’t follow the convention of the time and hold a mirror up to consumer tastes and preferences. Rather it shone a light on the brand and its unique story. It sought to persuade consumers of its merits, with a simple story stylishly told.

‘What the heart knows today, the head will understand tomorrow.’

James Stephens

Although Levi’s campaign was inspired by its heritage, it was not an exercise in dry historical narrative. First and foremost the advertising addressed the emotions. It suggested charismatic youth, heroic nonchalance and potent sexual chemistry. It promised freedom, escape, romance and rebellion.

Stripped of spoken words, the ads conveyed all this through compelling storytelling, impactful imagery and emotive music. As John Hegarty, the creative director behind it all, pointed out, ‘words are a barrier to communication.’

Emotional Product Demonstration

Despite the fact that the initial persuasive power of the campaign was emotional, it was also clear that consumers wanted rational reasons to justify their beliefs - to others and to themselves.

So amidst the stylish settings, slim heroes and sensuous music, the commercials always demonstrated the jeans’ functional attributes: their strength, durability and wear characteristics. 501s personalised with age and improved with wear. And the more you washed them, the better they got.

Creative teams found that such stories were excellent springboards for lateral ideas. And Hegarty dubbed this advertising approach ‘emotional product demonstration.’

Mass Marketing a Cult

From the outset there was some concern that, in broadening the appeal of a product originally beloved by a small group of cognoscenti, the brand would lose that critical group’s support. What if our opinion leaders sought exclusivity elsewhere? Wouldn’t this undermine the whole endeavour?

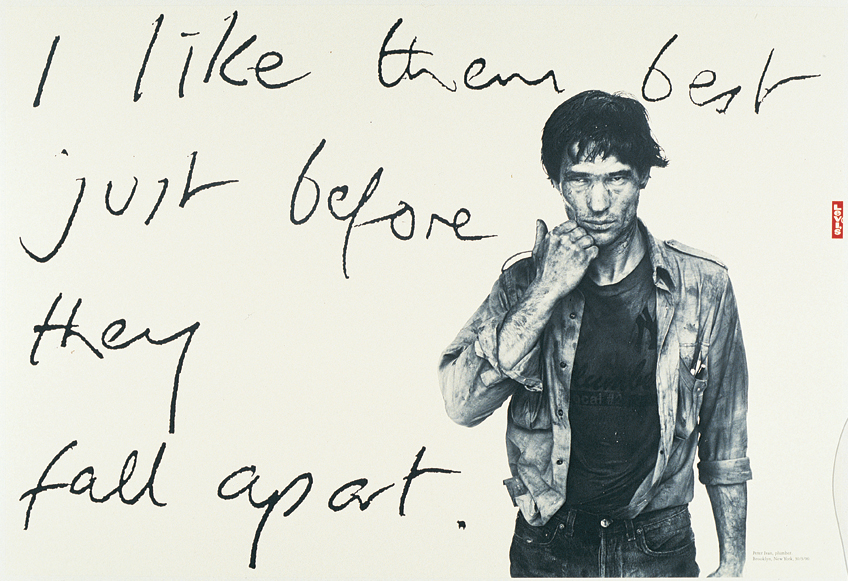

BBH determined that it was critical to sustain a relationship with opinion leaders. It developed print advertising that directly addressed them in their own discrete magazine titles (publications like The Face, iD and Dazed & Confused). It sponsored cutting edge bands and grass roots music events. And it offered Shrink-to-Fit and limited editions of the core product - something the cognoscenti could call their own.

The lesson was clear: never forget the people that first loved you.

‘Creek’ 1994 - BBH

United in Dreams, Divided by Realities

Levi’s soon looked to export the UK’s successful marketing to other European markets. This ought to have been challenging: back in the 1980s few campaigns crossed borders because local cultural differences were thought to be too great.

But BBH found that, though young people might be divided by the realities of their everyday circumstances, they were united in their dreams. The 501 campaign worked wherever the local youth aspired to independence and individuality; to original expression and the open road.

By the mid-1990s Levi’s was selling 50 million units per annum across Europe – and always at a premium price.

‘Move it on without moving it off.’

Nigel Bogle

With every new execution in the campaign, the pressure grew to sustain freshness and interest. How do you avoid predictability and familiarity? How do you avoid losing the baby with the bathwater?

The advertising struck a balance. It retained its chassis: the narrative structure; the aspirational hero; the dramatisation of product functionality. And at the same time it underwent constant restyling in its bodywork: the setting; the historical period; the tone; the filmic style; the particular product story.

Over the years 501 commercials were set in pool halls, drug stores and gas stations; in swimming pools, creeks and under the sea; in black & white, colour and animation; in the nineteenth century, the Depression and in outer space.

As BBH co-founder Nigel Bogle summarised: ‘We need to move it on without moving it off.’

Perhaps inevitably, the Levi’s 501 campaign did eventually run out of road. There was only so long that one brand could sustain mass loyalty to a single product in the fickle fashion category; only so long that the brand’s innovation could be primarily supplied by its marketing rather than by its product; and only so long that that brand could continue to grow volume and premium at the same time. Eventually the centre could not hold, and the market fragmented.

But it had been a pretty good run.

Levi’s print ad - Richard Avedon for BBH

So what did I learn from working on this great, but now long-gone, advertising campaign? I picked up a number of lessons about the fundamentals of persuasion that served me well for the rest of my career:

1. Don’t seek to add value, seek to reveal it.

2. Harness the support that you already have: fan the flames of discovery.

3. Embrace the power of narrative: simple stories stylishly told.

4. Lead with emotion: what the heart feels today, the head thinks tomorrow.

5. However much beliefs may be founded on emotion, give people rational justifications for those beliefs.

6. Never forget the people that first loved you.

7. Find the aspirations that unify people, rather than the realities that divide them.

8. Keep moving it on without moving it off.

Of course, today we live in an ever more complex, interconnected, fast-paced world. The landscape of marketing and communication is unrecognisable from the more innocent times of the late ‘80s and ‘90s. But I think many of these themes still resonate. And perhaps like 501s themselves, they improve with age.

(This piece first appeared in The Pembrokian, July 2018)

No. 200