John Craxton: The Heroic Hedonist

Still Life Sailors (1980-85) Estate of John Craxton

I recently took the train to Chichester to see an excellent exhibition of the art of John Craxton. (Pallant House Gallery, until 21 April 2024)

Though born and raised in England, Craxton produced much of his work in Greece. There he portrayed an Arcadia of ordinary folk living under a hot sun, amongst olive trees and asphodels, wild cats and frolicking goats. He painted young men smoking in the morning, sleeping in the afternoon and dancing into the night. His art is full of colour, light and movement. It is a joyous celebration of life, and prompts us to consider our own attitudes to work and play.

‘As a child I enjoyed a happy, near-Bohemian home life in a large family.’

Craxton was born in London in 1922. When his father, a pianist and composer, scored his only hit - ‘Mavis,’ sung by the legendary Irish tenor John McCormack - he took his wife and six children down to Selsey on the south coast and bought a shack above the beach.

Craxton had an idyllic childhood.

‘In what now seems like a succession of endless, if not cloudless, summer days, I ran barefoot, rode ponies, shrimped at low tide, collected fossils from the Bracklesham Beds, went to the movies, carried milk from the farm (which still had a working windmill) and had family picnics on the beach.’

Craxton decided as a young boy that all he wanted was to be an artist. He attended various schools, but emerged with no qualifications. A naturally independent spirit, he didn’t fancy the discipline of formal creative training either. And so he was largely self-taught, occasionally dropping into art schools to pick up equipment and a little drawing tuition.

Boy on a Blue Chair, 1946 John Craxton

Having failed an army medical, Craxton was excused war service. Always rather charming, witty and spontaneous, he fell in with various sponsors, lovers and artists, and one patron funded a studio in St John’s Wood that he shared with Lucian Freud.

His early work featured quiet country lanes, twisted trees and dead animals; solitary souls in melancholy, menacing landscapes. During the war years he was given his first solo exhibitions in London, and was commissioned to produce book designs – a line of work that served him well for much of his life.

But Craxton was keen to get away from Britain. As a teenager he had been enchanted by the ancient Greek figurines and pottery he encountered at the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Dorset. He aspired to a Mediterranean idyll.

‘The willow trees are nice and amazing here, but I would prefer an olive tree growing out of a Greek ruin.’

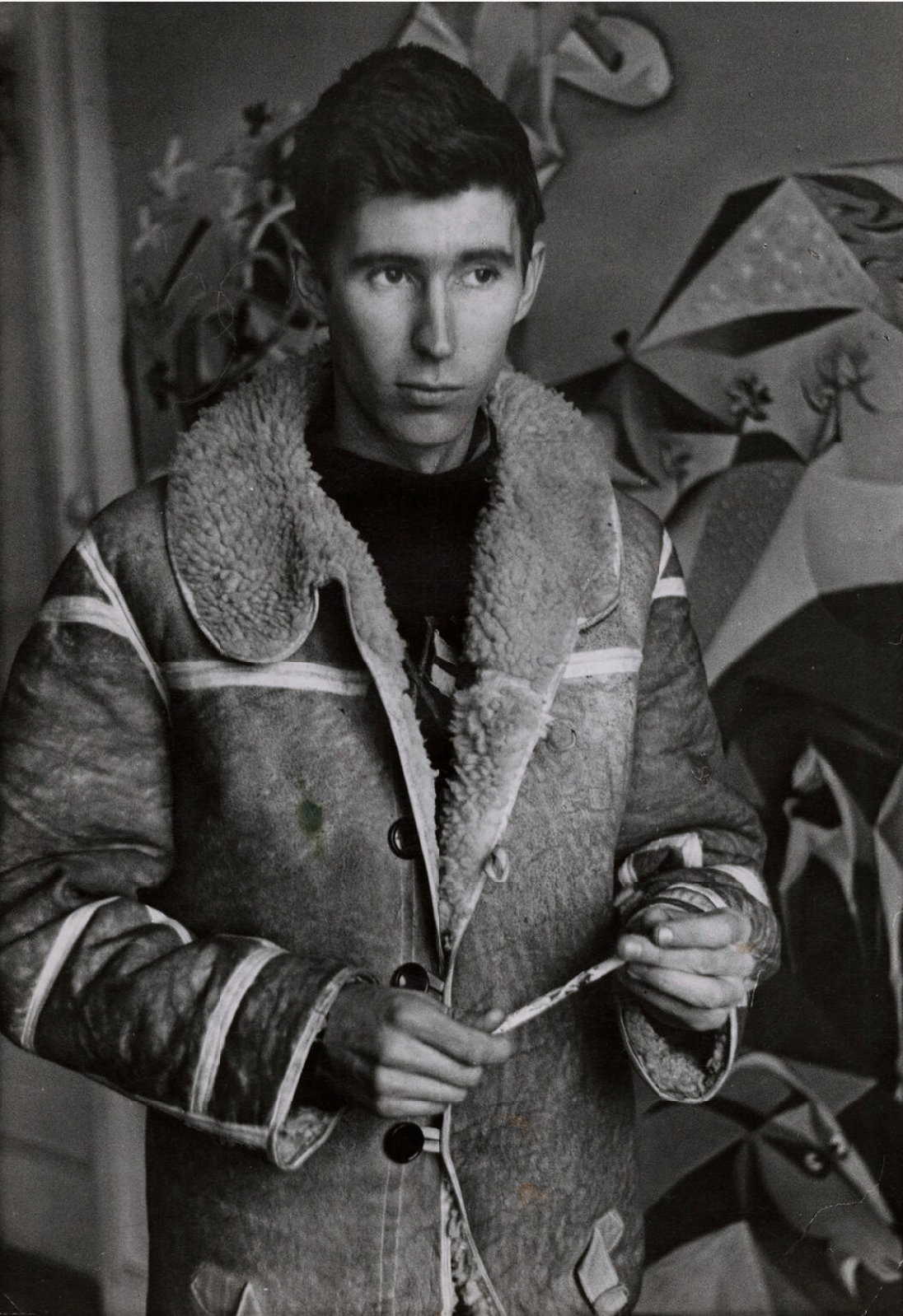

John Craxton by Felix H. Man

bromide print, 1940s© estate of Felix H. Man / National Portrait Gallery, London

Immediately after the hostilities ended, there were still strict restrictions on travel. So Craxton and Freud embarked on a painting expedition to the Scilly Isles, and then stowed away on a Breton fishing boat bound for France. They only got as far as Penzance.

The following year Craxton made it to Zurich, where he met the wife of a British ambassador at dinner. She offered him a lift to Athens in a bomber she had borrowed for a curtain-buying trip.

And so, aged 23, Craxton arrived in Greece and immediately fell under its spell. He settled first in Poros, and then Crete, and he would stay there, on and off, for the rest of his life.

‘It’s possible to be a real person – real people, real elements, real windows – real sun above all. In a life of reality my imagination really works. I feel like an émigré in London and squashed flat.’

In Greece Craxton created romantic landscapes populated by shepherds, peasants and a pipe-playing Pan. He painted the azure sea and cyan sky; bare footed young men in white cotton trousers and striped tee shirts - working, relaxing, dancing arm-in-arm. His art has vibrant colours and a gentle cubism. And by contrast with his previous work, there’s an exultant spirit, a dreamy languor, a warm conviviality. We meet a rugged herdsman, a smoking butcher, a grey-bearded octopus fisherman. Here are moustached mariners tucking into a meal of seafood and salad at the local taverna. A sign on the wall behind them warns against breaking plates.

‘The most wonderful sound in the world is of people talking over a good meal.’

Craxton was fond of saying that 'Life is more important than art.’ He relished the freedom he had on the Greek islands - to ride his Triumph Trophy motorcycle along dirt roads and mountain tracks; to talk and laugh at the dockside bars, as he drank ouzo and feasted on cuttlefish and calamari; to lead an openly gay life.

At the time Greece was a more tolerant place than Britain - although Craxton's interest in young men in uniform did prompt the authorities to suspect he was spying. When homosexuality was decriminalised in the UK in 1967, he sent the Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, a picture.

As well as painting, Craxton designed book jackets for the travel writer Paddy Leigh Fermor; and created stage sets for Frederick Ashton at the Royal Ballet. But he was not particularly industrious. His friends joked that he suffered from ‘procraxtonation.’

Pastoral for PW John Craxton

Craxton suggests that a creative life need not be fuelled by anxiety and pain. It doesn’t have to be all about struggle and denial. Rather we can choose to follow our dreams; pursue our passions; seek out the sun.

Craxton, who was made a British honorary consul in Crete, was never concerned by artistic fashion or the opinions of the establishment. He carried on painting in his own individual style into his later years, and he rode his motorbike until nearly 80. When he died aged 87, his ashes were scattered in Chania harbour.

His biographer Ian Collins described him as ‘a heroic hedonist.’

'My life, my life, my life, my life in the sunshine.

Everybody loves the sunshine.

Sunshine, everybody loves the sunshine.

Sunshine, folks get down in the sunshine.

Sunshine, folks get 'round in the sunshine.

Just bees and things and flowers.

My life, my life, my life, my life in the sunshine.

Everybody loves the sunshine.

Feel, what I feel, when I feel, what I feel,

When I'm feeling, in the sunshine.

Do what I do, when I do, what I do,

When I'm doing, in the sunshine.

Sunshine, everybody loves the sunshine.'

Roy Ayers, 'Everybody Loves The Sunshine'

No. 453