Suffragette for a Day: The Limitations of Immersive Experiences

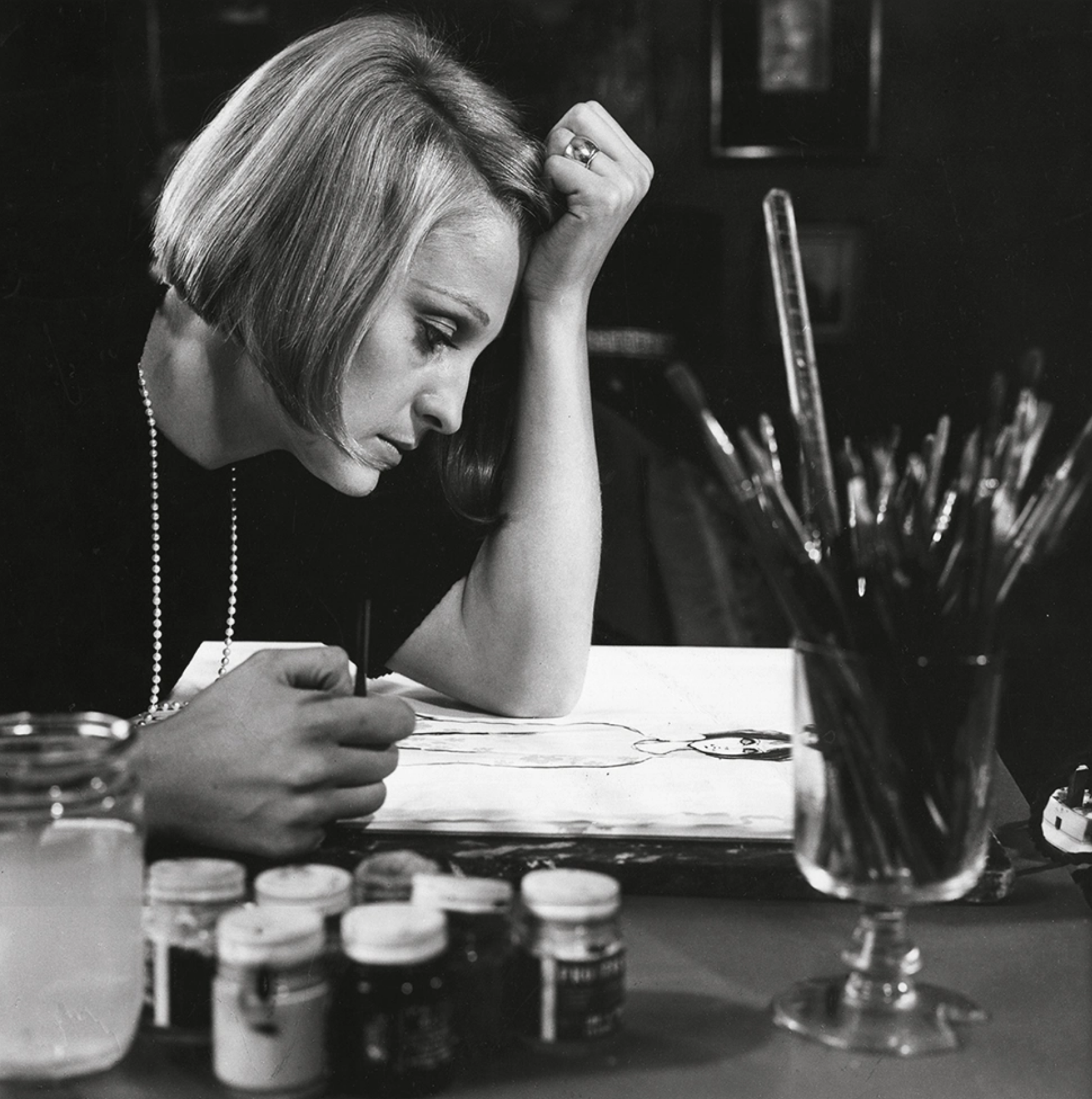

Surveillance photographs of suffragettes who had been imprisoned in Holloway.

Crown Copyright, courtesy of The National Archives.

2018 marked 100 years since the UK Government passed the Representation of the People Act, giving the right to vote to 8.4 million women who were over the age of 30 and met minimum property qualifications. It was the first step towards equalizing the franchise.

I thought it would be interesting to watch a play on the subject, but I could find nothing in the mainstream West End venues. And so I settled instead for a couple of tickets to an immersive theatre event.

Early one bright summer’s evening, my wife and I tentatively made our way down into the basement of the Trocadero shopping centre on Piccadilly. We were met by a group of severe women in long heavy Edwardian skirts and white cotton blouses, and informed that we had travelled back in time to 1912. Taken to an office, the two of us were then formally enlisted to the suffragette cause and warned of the risk of incarceration and the loss of our reputations.

Next we were sent back out onto the street to perform our first act of protest. Handed a piece of chalk each, we had to write appropriate slogans on the paving stones around the Trocadero.

This seemed simple enough. With shoppers and tourists traipsing past on either side, I got down on my knees and scrawled in large capital letters:

'Votes for Women.’

I admired my work for a moment, and then added:

‘Deeds, not words!’

No one seemed to be paying too much attention. Which was fine, as I was a little concerned that I’d bump into one of my former colleagues, whose offices were close at hand.

After a little while, having written the same lines a few more times (my creativity eluded me), we decided that we’d made our point, and it might be time to return to our basement HQ.

In the tea-room, which was decorated in green, white and purple, some of our fellow conspirators were painting banners, making rosettes and learning a protest song.

We were briefed on another mission. We were to have a secret rendezvous with a man in a bowler hat by the statue of Eros on Piccadilly Circus.

Before we set off, our instructor assumed a grave expression.

’I need to check with you one more time. Are you prepared to break the law for the cause?’

‘Yes, absolutely.’ I nervously replied. ‘Not a problem.’

Above ground once more, we didn’t have long to wait before we spotted a tall gentleman smartly attired in a sombre suit and a black bowler hat. As we approached, we realised he was holding a couple of large stones.

‘I want you both to take these rocks and throw them through the windows of Lillywhites sporting goods store. It’s just over there.’

‘Of course. Got it. All good.’

Not a natural seditionary, I nonetheless steadied myself and took aim at a display of cricket equipment. I had just coiled my arm behind my back, when we were seized by a couple of burly uniformed police officers. We were then separated, taken to some grim underground cells and interrogated.

My inquisitor was sarcastic, aggressive, belittling, and I was given a hard time for my ‘Fenian name.’ To be fair, he didn’t beat me up. Which I suspect would have been on the cards back in 1912.

All in all, my immersive experience was rather unsettling. But what did I learn from my day as a suffragette?

The event was certainly carefully crafted and intelligently scripted. And it did bring home the harsh realities of breaking the law for a cause.

But at the same time, I concluded that immersive theatre is not really for me. I’m too awkward and self-conscious. I find it hard to let go. And I’m not sure that a piece of personally involving drama could ever do justice to the horrors of oppression.

We’re all aware of the view that experience is the route to proper comprehension.

'I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.’

Xunzi

But perhaps we need to be mindful that immersion is not appropriate to everything and everyone. Sometimes it’s fine just to show and tell.

When my wife and I were reunited, on bail, in the tea-room of the suffragette HQ, we exchanged glances.

‘Maybe we’ve done enough agitation for one day?’

‘Yes, I think so. Let’s go to dinner.’

'Comrades, ye who have dared,

First in the battle to strive and sorrow,

Scorned, spurned, nought have ye cared.

Raising your eyes to a wider morrow.

Ways that are weary, days that are dreary,

Toil and pain by faith ye have borne;

Hail, hail, victors ye stand,

Wearing the wreath that the brave have worn!

Life, strife, these two are one,

Nought can ye win but by faith and daring:

On, on that ye have done,

But for the work of today preparing.

Firm in reliance, laugh a defiance,

(Laugh in hope, for sure is the end)

March, march, many as one.

Shoulder to Shoulder and friend to friend.’

‘The March of the Women’, Ethel Smyth, Cicely Hamilton

No. 491