The Quiet Achiever: Learning Lessons from RBG

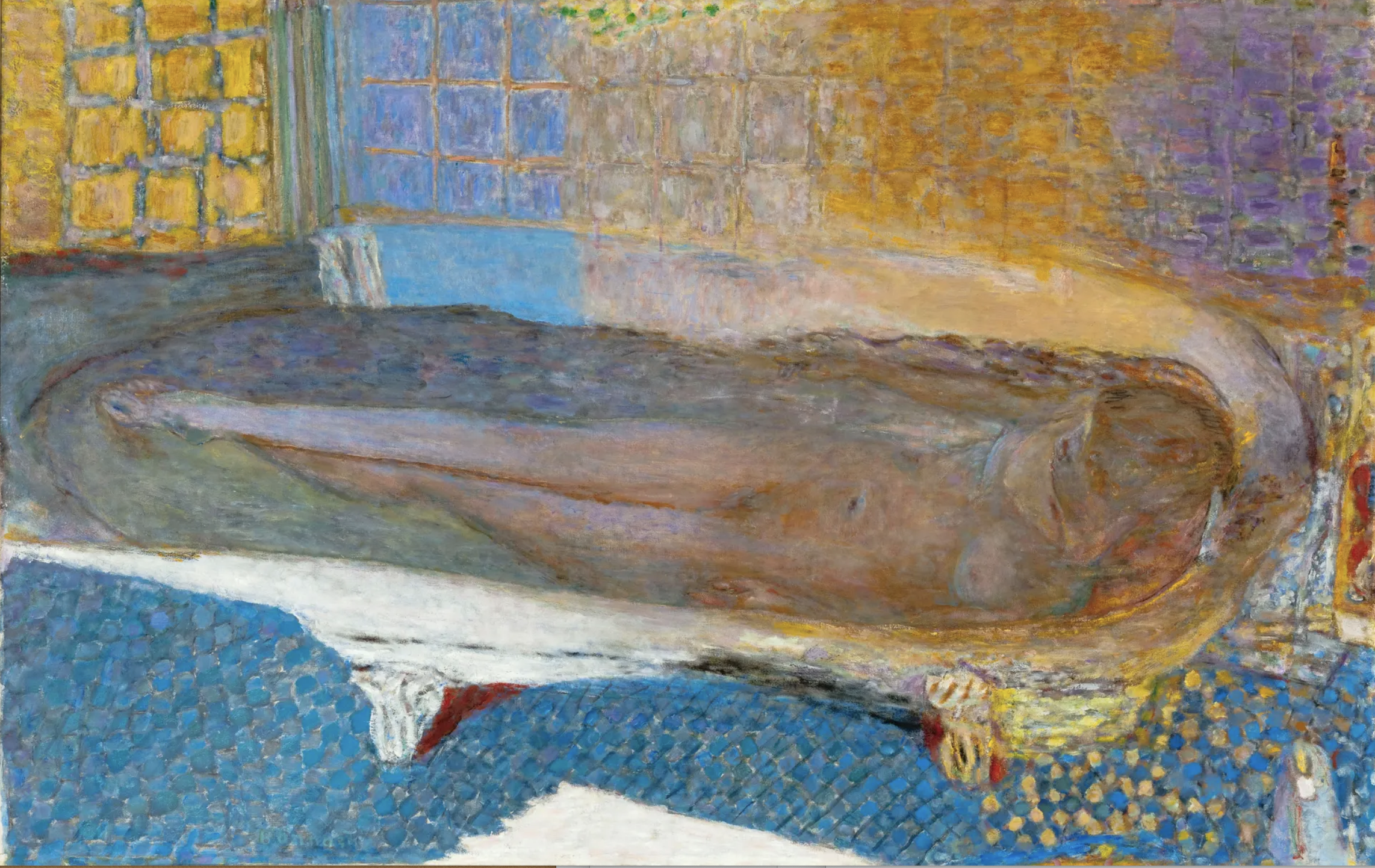

Ruth Bader Ginsburg Photograph by Irving Penn / © Condé Nast 1993

'I am a Brooklynite, born and bred, a first generation American on my father’s side, barely second generation on my mother’s. What has become of me could happen only in America. Neither of my parents had the means to attend college, but both taught me to love learning, to care about people, and to work hard for whatever I wanted or believed in.'

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

I recently watched an excellent documentary about US Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg (‘RBG’). It’s the story of an incredibly talented, resilient woman who overcame the odds, step-by-step, to help build a secure legal framework for women’s equality in the US.

Ruth Bader was born in 1933 in a working-class neighbourhood of Brooklyn, and earned the family nickname Kiki for being a ‘kicky baby.’ She was encouraged to take her education seriously by her beloved mother, who passed away just as she finished high school. She studied government at Cornell and married fellow student Martin Ginsburg a month after graduating. They had their first child in 1955, and subsequently both enrolled at Harvard Law School.

Soon, however, Martin contracted testicular cancer. Ruth found herself caring for her young daughter and convalescing husband, attending both his classes and her own.

This was challenging enough. But at Harvard Ruth also had to endure a hostile, male-dominated, environment. There were only eight other women in her class of more than 500, and on joining they were admonished by the Dean for taking the places of men.

When in time Martin recovered and graduated, the couple moved to New York so that he could take up a job as a tax lawyer. Ruth completed her degree at Columbia Law School, and was the first woman to be a member of both the Harvard and Columbia Law Reviews. In 1959 she graduated joint-first in class. And yet, when she went looking for work, she didn’t receive one job offer from a New York law firm.

'I was Jewish, a woman, and a mother. The first raised one eyebrow; the second, two; the third made me indubitably inadmissible.'

Ruth settled for a career in academic law, teaching at Rutgers University Law School and at Columbia. At Rutgers she was informed she would be paid less than her male colleagues because she had a husband with a well-paid job.

No surprise perhaps that Ruth gravitated towards the study and teaching of women’s rights. In most states at that time you could be fired for being pregnant; banks required a woman applying for credit to have their husband co-sign; marital rape was rarely prosecuted. Indeed hundreds of separate statutes across the country discriminated on the basis of sex.

‘The gender line helps to keep women not on a pedestal but in a cage.’

In 1972 Ruth co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Rather than seeking to end all gender discrimination at once, she determined to take it on one law at a time. As Director of the ACLU she challenged laws giving different access to housing benefits to male and female service members; different survivor benefits to men and women; different minimum drinking ages for men and women. She challenged a law enabling women to opt out of jury service. And more besides.

Methodical, precise, considered, Ruth gradually chipped away at the edifice of sex discrimination. She concentrated on winnable cases. Sometimes she represented male plaintiffs to demonstrate that gender discrimination harmed both men and women. She referred to gender rather than sex so as not to distract male judges.

‘I knew that I was speaking to men who didn’t think there was such a thing as gender discrimination. And my job was to tell them that it really exists.’

Between 1973 and 1976 Ruth argued six gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court, winning five. This was a step-by-step revolution.

‘This opinion does mark as presumptively invalid a law that denies to women equal opportunity to inspire, achieve, participate in and contribute to society based on what they do.’

In the documentary Ruth’s children bear witness to her phenomenal stamina throughout this period. Sustained by coffee and prunes, she worked into the early hours every night, and was at court by 9-00 the next morning. At the weekend she slept.

Beyond working incredibly hard to achieve one’s goals, there are a number of lessons we can learn from Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She teaches us to be clinical and cool headed in the design and execution of strategy; to pick our battles; to fight them in the right order; and to be sure of winning. That way we will win the war.

I was particularly struck by Ruth’s working method. She was not a militant firebrand, given to marching and demonstrating. Rather she was serious and soft-spoken, cautious and careful, reserved and restrained. Her colleagues report that she didn’t do small-talk. She just focused on getting the job done.

'When a thoughtless or unkind word is spoken, best tune out. Reacting in anger or annoyance will not advance one’s ability to persuade.'

Ruth Bader Ginsburg At work

Ask yourself this: Do you have an RBG in your office? Sitting silently, working diligently. Meticulous and methodical. Shy and self-effacing. The quiet achiever, the unsung hero.

What if she or he is being shouted down, pushed aside, managed and marginalised? What if the conversation is being dominated by the most vocal rather than the best qualified people in the room? Are you doing enough to ensure that the quiet achiever can still be heard?

'We have the oldest written constitution still in force in the world, and it starts out with three words, 'We, the people.''

In 1980 Ruth Bader Ginsberg was appointed to the US Court of Appeals, and in 1993 she became the second woman Justice on the US Supreme Court. In recent years, with liberal Justices in the minority, she has often been a dissenting voice.

Sadly Martin Ginsburg died of cancer in 2010. He and Ruth had been married for 56 years. In December 2018 Ruth, already a two-time survivor of cancer herself, underwent surgery for lung cancer. She was back on the Supreme Court bench eight weeks later. She has recently turned eighty-six.

Just over five feet tall; hair neatly tied back with a scrunchie; serious glasses; vintage earrings; silk shirt and scarf. Ruth Bader Ginsburg is asked how long she can keep going. With lips pursed, she pauses for thought.

‘I will do this job as long as I can do it full steam, and when I can’t that will be the time I will step down.’

Full steam ahead, Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

No. 222