Afraid to Dance: Learning to Let Go As the Pressure Mounts

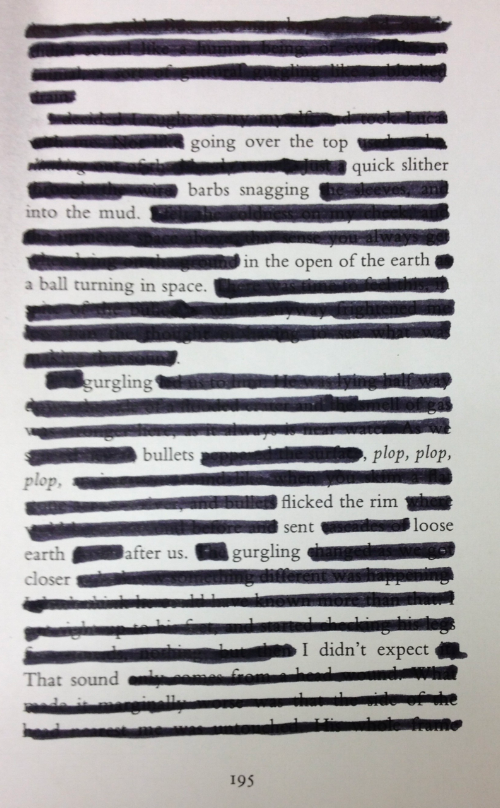

The dancing mania by Hendrik Hondius. Source: Wellcome Library, London

One day in July 1518 Frau Troffea stepped out onto the narrow streets of Strasbourg and began to dance. She swayed and shimmied, bobbed and boogied, with self-absorbed abandon. She danced for hours on end, not giving a thought to rest or sustenance. Hours turned to days. Within a week 30 or so others had joined in. Within a month there were 400 crazed dancers clogging the streets. The authorities were nonplussed. They laid on musicians to accompany the revellers, opened up halls and public spaces, in the belief that through encouragement they could drain the dance away. Inevitably many collapsed from exhaustion and some died of heart attacks.

The Strasbourg Dancing Plague was just one of a number of incidents of choreomania that were reported across Europe in the Middle Ages. Scholars have suggested that these were episodes of mass, stress-induced psychosis, brought on by the harsh conditions of medieval life. Some think that cult religions were involved. Others have speculated that fungus growing on local rye crops may have produced a psychoactive drug similar to LSD.

Whatever the specific cause, there’s no doubt that fear of dancing has a very particular grip on the popular imagination. In the late Middle Ages murals and woodcuts depicted Danses Macabres in which skeletons escorted people from all walks of life in a jaunty jig to the grave. In seventeenth century England Oliver Cromwell banned maypole dancing for its sinfulness and suggestion. The nineteenth century ballet Giselle features the Wilis, ghostly spirits of women betrayed by their lovers, who when they encounter men, dance them to death. In Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale, The Red Shoes, a pair of shoes refuses to let their occupants stop dancing.

What’s going on here? Of course we all love to dance. Well, most of us do. But maybe, at another level, we’re also afraid to dance. Dance represents succumbing to the sensual and emotional; a rejection of hierarchy and convention; a loss of control. Dance takes us back to our primitive roots. We danced before we could speak. It takes us to a world of instinct and intuition, of the euphoric and ecstatic. In dance we find release from our social shackles. We let go. And so as a culture we want to dance and yet we are afraid to dance.

In the creative industries we should recognise these contrary forces. We are forever managing the tension between the desire for freedom of expression and the need to take command of a situation. Creativity demands carte blanche; commerce demands control.

This tension is felt most acutely when the stakes are high: when the Clients are most expectant; when the prize is most exciting and the penalty is most disturbing; when time is running out. And it’s at precisely these times that the instinct to take control usually wins out. When we’re in a crisis we concentrate on cracking the idea at every moment of the day; we focus on finding the answer with every fibre of our bodies. The more arduous and important the undertaking, the more seriously we tend to take it.

But pressure can be counterproductive. By concentrating too intensely on a problem, we diminish our ability to solve it. We become cautious, conservative, blinkered and narrow minded.

In fact the creative’s best response to pressure should be to puncture it; release it. Because it’s only when we are at ease, when our minds are unfettered and free to wander, that we make random connections, have lateral thoughts and serendipitous encounters. At times of crisis we should learn to let go.

So as the tension mounts and the deadline looms, always remember to step outside. Go for a walk, go to the gym, go to sleep. Change the routine, change the subject, change the record. Look at the sky, read a book, call your mum. And don’t be afraid to dance.

‘Let’s groove tonight.

Share the spice of life.

Baby slice it right.

We’re gonna groove tonight.

Let this groove light up your fuse.

It’s alright (alright), oh, oh.’

Earth Wind & Fire, Let’s Groove (Maurice White, Wayne Vaughn)

No. 135