The Nun in the Cathedral: Beware the Inclination to Go with the Flow

Diego Velasquez, ’The Nun Jeronima de la Fuente'

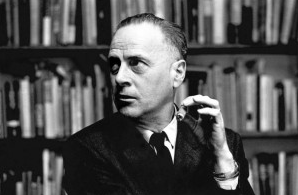

'Most of our assumptions have outlived their uselessness.'

Marshall McLuhan

I’m not sure I consider myself a holiday expert. I don’t really like the heat or beaches or exotic food; the awkward new acquaintances, scatter cushions and exacting shower mechanics. And I’ve never quite mastered the flip-flop.

I am nonetheless partial to an Italian Tri-Centre Break. This vacation format works on the assumption that every Italian town has some decent restaurants and a couple of charming churches; an agreeable piazza filled with old folk drinking coffee, a gallery stocked with unfamiliar Renaissance art - entirely sufficient to merit a couple of nights’ stay. And if you cluster a few of these towns together, you arrive at a very satisfactory holiday. Bologna-Ravenna-Parma; Cremona-Mantova-Verona; Vicenza-Padova-Ferrara. Ideal!

Like everyone else, I try to be ‘a traveller, not a tourist.’ Not easy for a bloke from Essex. One tactic I occasionally employ is to attend Sunday Mass at the local Cathedral. For an hour I can blend in with the natives in a space devoid of sightseers. I can feel like I belong.

On a visit to Parma some years ago, having ascertained from my hotel the times of services, I arrived at the Duomo just as they were clearing out the tourists. With a confident gesture I signalled that I was there for Mass and settled into a central pew with my fellow Parmensi. I took some time to observe my neighbours, sat back and admired the impressive architecture. I fitted in.

A small elderly Nun handed me an Order of Service and mumbled some words of welcome in Italian. ‘Bene grazie’ I replied with a smile and what I’m sure was a very convincing accent.

The church gradually filled up. It was quite a big place and we had a pretty good turnout. At ten o’clock precisely, with the toll of a bell and a short procession of candles, thuribles and priests in colourful vestments, the Mass began. Although the service was in Italian, of which I know only a few words, it all progressed along familiar lines. I was aware when to nod and bow and cross myself and so forth, and felt an all-consuming sense of belonging.

Then a peculiar thing happened. When it came to the time for the Readings, the whole affair, which had been going so smoothly, suddenly ground to a halt. No one had taken up a position at the lectern. People began looking round at the other attendees. The Duomo echoed with confused whispering.

At length the Nun I had met at the outset - who was now sitting in the front row - turned right round in her bench and, with a formidable glare, pointed towards the centre of the congregation. I followed the line of her arm, carefully calculating the geometry of her posture, and concluded, with a certain amount of anxiety, that she was pointing squarely in my direction.

It was at this juncture that I glanced at my Order of Service and realised that no one else around me had been given one. Perhaps those mumbled words from the elderly Nun had been more than a welcome. Perhaps they had been an invitation to read the Lesson.

I promptly hid the incriminating paper under my seat, looked intently at the floor and began to sweat profusely. I could sense that the eyes of the whole congregation were now upon me. I was determined not to budge.

After what seemed like an eternity, the Nun herself took the stand and delivered the Readings. Order was restored and the Mass regained its impetus. At the end of the service I made a quick bolt for the exit. I didn’t quite feel that I belonged any more.

'It is useless to attempt to reason a man out of a thing he was never reasoned into.'

Jonathan Swift

So much of what we do in life is based on false assumptions, outdated suppositions, wrong information. Yet we are driven by inertia, carried along by our own momentum, floating on a cloud of misplaced confidence. We want to fit in. We want to belong. We follow the crowd and go with the flow. We nod our assent. We unthinkingly conform. We laugh at jokes we don’t really comprehend. We agree to actions we don’t really endorse. We say ‘yes’ when we should really be saying ‘no’.

It takes conscious effort, an act of will, to dismiss the urge to belong; to resist the force of momentum in our lives; to stop for a moment, reflect and ask: ‘Why?’

‘No, no, no.

You don't love me

And I know now.

No, no, no.

You don't love me,

Yes I know now.

'Cause you left me, Baby,

And I got no place to go now.’

Dawn Penn, ‘You Don’t Love Me’ (Cobbs / Mcdaniel)

No. 300