Edward Hopper: The Lonely City

Edward Hopper - Automat (1927)

'All I ever wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.’

Edward Hopper

I recently watched an insightful documentary about the artist Edward Hopper. (‘Hopper: An American Love Story’ (2022) by Phil Grabsky)

Hopper painted beguiling pictures of ordinary folk and everyday lives - individuals lost in thought; groups of people, each isolated and remote; private dramas played out in public places. He created a brooding world of alienation and ennui, and distilled a truth about the modern urban experience: that we can be living and working in a vibrant, bustling city, surrounded by entertainment, community and opportunity – and yet still feel terribly empty and alone.

'In every artist’s development, the germ for the later work is always found in the earlier. What he once was, he always is, with slight modifications.'

Hopper was born in 1882 in Nyack, New York, the son of a dry-goods merchant. He grew up in an affluent, intellectual Baptist household, and from an early age he was encouraged to draw by his mother. Having enrolled at the New York School of Art and Design, he subsequently took up a career in commercial illustration, a job he detested.

‘Well, illustration really didn’t interest me. I was forced into it by an effort to make some money, that’s all.’

Edward Hopper - Office At Night (1940)

In his early 20s Hopper made three trips to Paris, where he pursued his studies in literature, language, architecture and art. Naturally conservative, while in the French capital he avoided the avant-garde. He was a tall, shy, awkward young man, whose first romantic encounters were overwrought and frustrating. In 1910 he returned to the United States, and thereafter never left.

'I am very much interested in light, and particularly sunlight, trying to paint sunlight without eliminating the form under it, if I can.'

From the outset Hopper was fascinated by light and shadow, and he often painted urban and architectural scenes - stairways and window frames; porticos and pavements; turrets, towers and mansard roofs. His city pictures were sparsely populated, or devoid of people entirely. They had an eerie stillness.

Hopper’s early work was poorly received, rarely exhibited and seldom sold. He remained on the margins for many years. This was all to change in 1923, when, on a summer painting trip in Gloucester, Massachusetts, the 41 year old encountered Josephine Nivison, whom he had known at art school. She was his opposite - short, talkative and sociable - and she set about taking this intense, introverted man in hand.

Nivison persuaded the Brooklyn Museum to include some of Hopper’s work alongside her own in a forthcoming show. One picture was purchased by the museum for $100, and from that point on he was set fair.

Hopper and Nivison married in 1924 and settled into his Washington Square apartment in Greenwich Village, where they resided for the rest of their days. He was at last able to give up his job as an illustrator.

'The only real influence I've ever had is myself.’

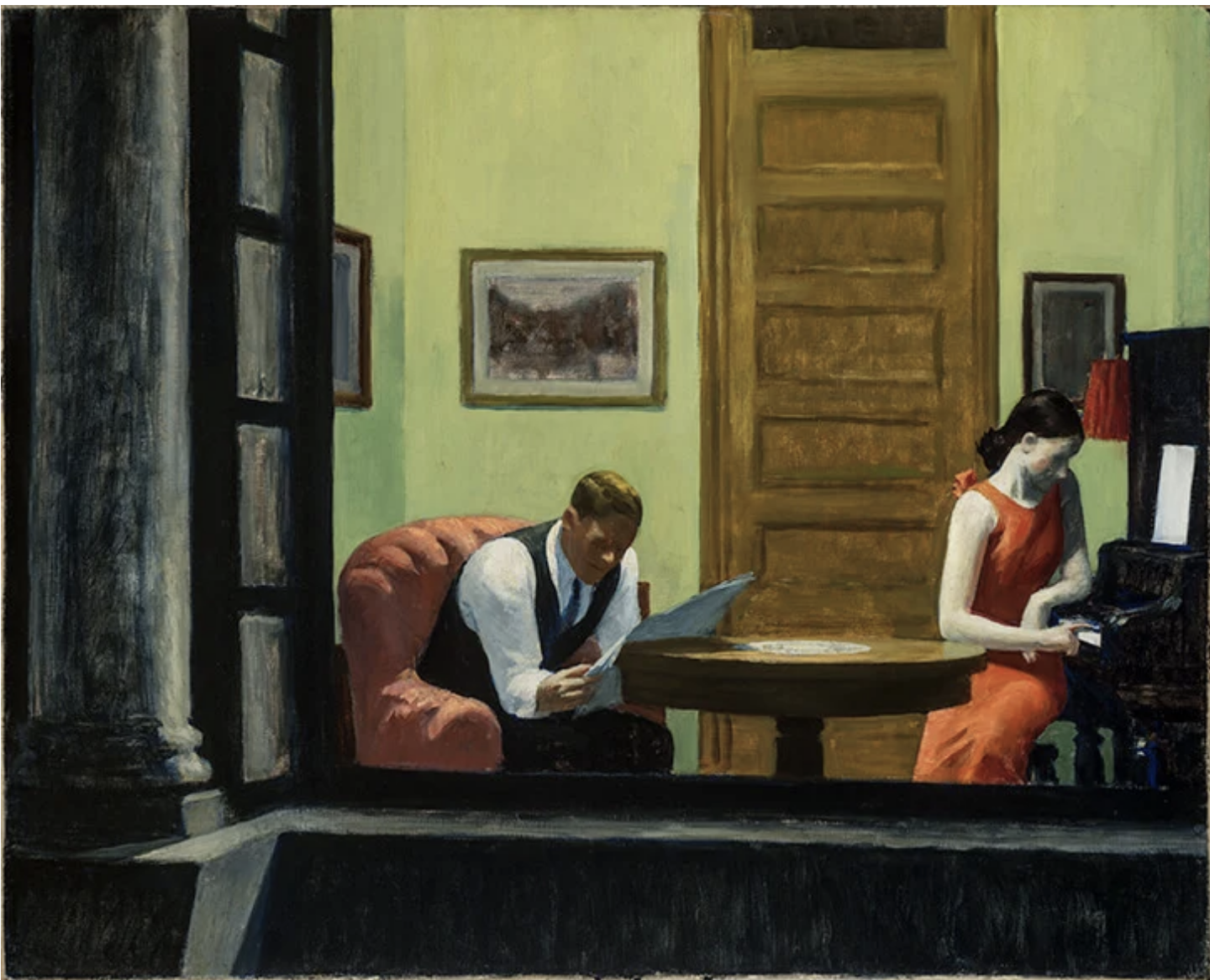

Edward Hopper - Room in New York, 1932.

Hopper’s most celebrated paintings present seemingly mundane moments in the lives of ordinary people. They have a voyeuristic feel and sometimes their subjects are as if spied from a distance. (In his youth Hopper had enjoyed observing life in the streets, offices and residential buildings as he travelled by train into New York.) The viewer is invited to speculate: Who are these characters? What are they thinking about? What is really going on here?

A bald fellow in a white shirt with sleeve garters sits on the sidewalk smoking a cigar, absorbed in his own private world. A middle-aged man methodically rakes the lawn of the garden adjoining his clapboard house. It’s 11-00AM and a woman with long dark hair leans forward in her armchair to stare out of the apartment window. She is naked but for a pair of flats. At the automat a lady in a cloche hat and jade green coat concentrates on her coffee. A woman in a pink slip perches on her bed and soaks up the morning sun. A pensive female usher, in smart blue uniform, leans against the wall of the movie theatre, her blond hair illuminated by a side lamp.

There’s a cinematic quality to Hopper’s work. No surprise perhaps as he and Nivison often took trips out together to the movies or the theatre.

'When I don't feel in the mood for painting I go to the movies for a week or more. I go on a regular movie binge!'

When Hopper paints more than one subject, the characters rarely interact, touch or look at each other. We see them assembling in the hotel lobby, dining at the restaurant, reading on a train. They are together, but apart. An executive works at his desk, while nearby his assistant silently gets on with her filing. Three customers sit at the cherry-wood counter of a diner. Drinking coffee, eating a sandwich, smoking a cigarette. Each seems preoccupied. A smartly dressed couple relax at home. He reads the paper intently, she half-heartedly plays a few notes on the piano.

There’s a melancholy sense of disappointment in these images; of boredom and bewilderment. What has happened? How did I get here? Is this it?

'Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world.’

Edward Hopper - Self-Portrait (1925–1930)

In the mid-1930s Hopper and Nivison built a summer-house in South Truro on Cape Cod and they went on field trips for fresh material in their 1925 Dodge. They had a troubled, but enduring marriage. She subordinated her career to his, managing his appointments and sharing his reclusive life-style. He was generally withdrawn and aloof, and was rather dismissive of her art. He nonetheless used her as the model for all his female characters - just changing the faces.

Hopper was a slow, meticulous painter and he made many compositional sketches before he was comfortable with a scenario. His output could be as low as two pictures a year.

‘One good picture is worth a thousand inferior ones.’

He didn’t like interviews and he avoided explaining his work.

‘The whole answer is there on the canvas. If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.’

Once, when asked what his artistic objective was, he simply replied:

‘I’m after me.’

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that this silent, secretive, introspective man was presenting us with his own sense of alienation and isolation; his own interior sadness.

'So much of every art is an expression of the subconscious that it seems to me most of all the important qualities are put there unconsciously, and little of importance by the conscious intellect. But these are things for the psychologist to untangle.'

Edward Hopper - New York Movie (1939)

It struck me that in the world of work we make many assumptions about our colleagues’ wellbeing and state of mind. We imagine that - because ours is a youthful, vigorous, convivial industry; because the city is such a dynamic, inspiring, populous place – our fellow employees are fulfilled and satisfied, content and connected. We put on parties, inductions and talks to fuel their enthusiasms. We send upbeat missives and promote unifying values. We celebrate success. But we too often fail to understand that many of our colleagues feel remote and detached. They are lost in the lonely city.

'I have tried to present my sensations in what is the most congenial and impressive form possible to me.'

Hopper died in his Washington Square studio in 1967. Nivison passed away ten months later. One of his last paintings simply presented sunlight and shadow falling across an empty room.

'Mother, I tried, please believe me.

I'm doing the best that I can.

I'm ashamed of the things I've been put through,

I'm ashamed of the person I am.

Isolation, isolation, isolation.’

Joy Division, ‘Isolation’ (S Morris / I Curtis / B Sumner / P Hook)

No. 435