Francis Bacon and the ‘Trail of Human Presence’: If You Want to Get Closer to Someone, You Need to Stand Farther Away

Head of a Boy - Francis Bacon, 1960

I recently visited an excellent exhibition of portraits by Francis Bacon. (‘Human Presence’ runs at the National Portrait Gallery, London until 19 January.)

'How are you going to trap appearance without making an illustration of it?'

Francis Bacon

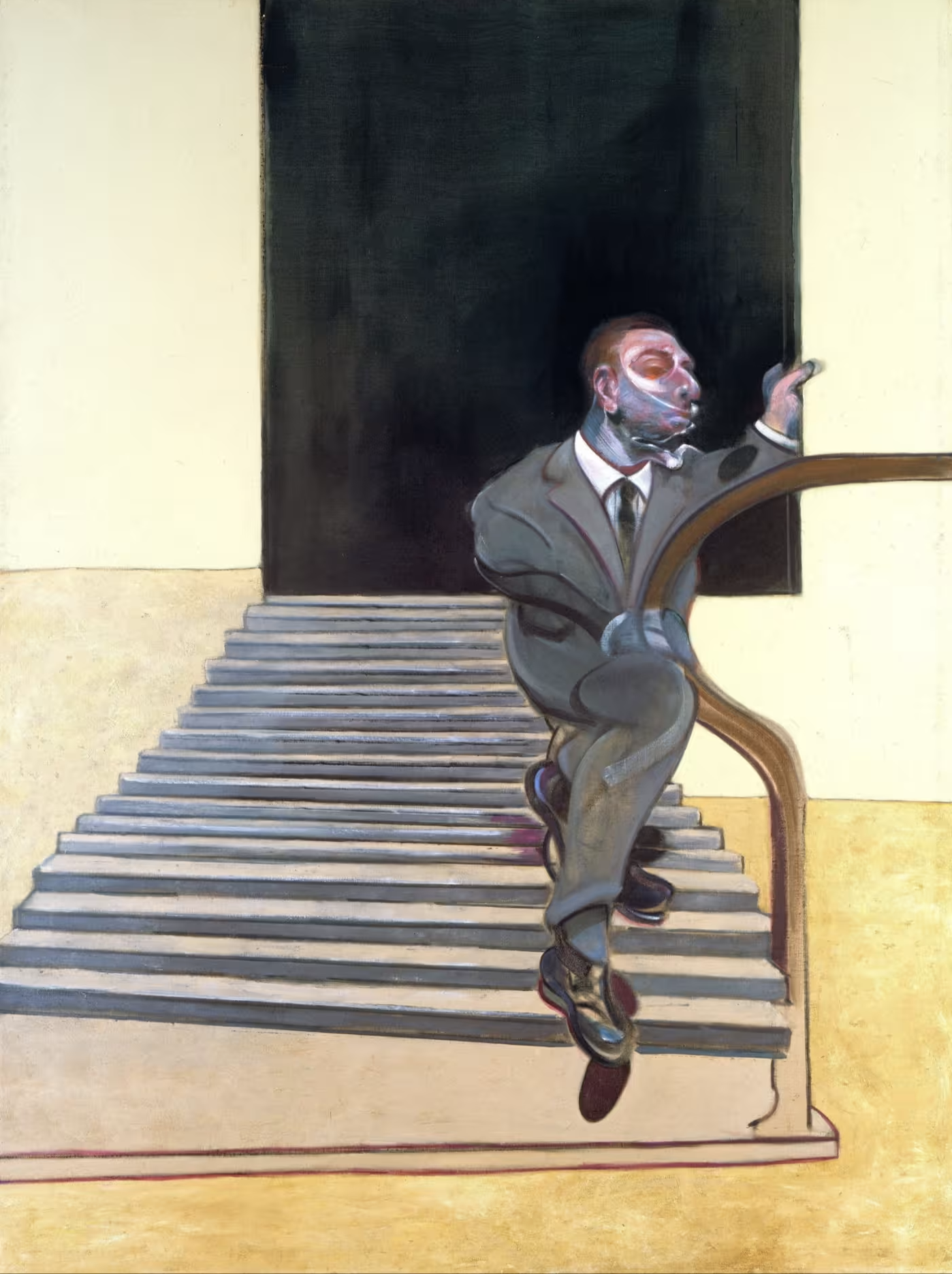

Bacon’s approach to portraiture was very much his own. His made his figures twist in torment and howl in anguish, so as to express latent anxieties and visceral fears. He distorted the human form, bent and buckled it, so as to articulate emotional intensity. He drew on stimulus unrelated to the sitter, merged identities and subverted reality, so as to establish truth. Warped, bruised and disfigured, corrupted and contorted, painted against black backgrounds or veridian green walls, sometimes his subjects seemed to emerge from the darkness; sometimes they receded into it.

Self Portrait - Francis Bacon, 1973

‘In painting a portrait, the problem is to find a technique by which you can give over all the pulsations of a person…The sitter is someone of flesh and blood and what has to be caught is their emanation.’

Born into a wealthy Dublin family in 1909, Bacon was raised in Ireland and England. Scarred by a difficult relationship with his father (who struggled to come to terms with his emerging homosexuality), he had a troubled childhood. He ran away from school and drifted through his teenage years in London, Berlin and Paris, living off an allowance, taking occasional jobs and dodging the rent.

‘I’m always surprised when I wake up in the morning.’

Bacon worked for a time as an interior designer, but, after seeing a Picasso exhibition in Paris, he determined to take up painting. Although he had no formal art training, he had developed a broad appreciation of avant-garde cinema, photography and literature.

‘I think art is an obsession with life and, after all, as we are human beings, our greatest obsession is with ourselves.’

‘Portrait of a Man Walking Down Steps’ - Francis Bacon, (1972) © The Estate of Francis Bacon/DACS

While many young artists at the time were exploring abstraction, Bacon committed to portraiture. His portraits of the late 1940s featured screaming men, trapped or shackled within transparent cages, in the midst of unspeakable nightmares, impotent in the face of unknown terrors.

‘I think of life as meaningless; but we give it meaning during our existence.’

Bacon was endeavouring to strip away artifice and display; to reveal the dark truths of human nature, the violence and horror he saw behind our defensive masks and shields.

‘We nearly always live through screens… I sometimes think, when people say my work looks violent, that perhaps I have been able, from time to time to clear away one or two of the veils or screens.’

From the early 1950s Bacon focused on portraits of friends and lovers: the artists Lucian Freud and Isabel Rawsthorne; the artist’s model Henrietta Moraes (who worked for a time in an ad agency); his partners Peter Lacy and George Dyer; the proprietor of Soho club The Colony Room, Muriel Belcher (who paid him £10 a week and free drinks, in return for attracting new clientele). And he often painted himself.

‘I couldn’t [paint] people I didn’t know very well…It wouldn’t interest me to try to…unless I had seen a lot of them, watched their contours, watched the way they behaved.’

Initially Bacon worked with sitters in the studio, painting from life. But he became uncomfortable with this approach.

‘I find it less inhibiting to work from them through memory and their photographs than actually having them seated there before me.’

Bacon turned to his friend Roger Deakins to take photographs of his subjects as a reference. He was also inspired by other sources: by magazine images, book illustrations and film stills; and by old master paintings, particularly Rembrandt’s self-portraits and Diego Velazquez’s depiction of Pope Innocent X.

‘I became obsessed with this painting, and I bought photograph after photograph of it. I think really that was my first subject.’

Three Studies for a Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne - Francis Bacon

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved / DACS

And so, in one portrait we see the cracked glasses from the 1925 movie ‘Battleship Potemkin’; a painting of Freud is based on a photo of Franz Kafka; a self-portrait is derived from a photo of Freud; an image of Lacy originates from a holiday snapshot; and a depiction of Lisa Sainsbury has echoes of a bust of Nefertiti.

Bacon’s studio floor was littered with such reference material: pages torn from books and magazines, crushed, folded and splashed with paint: images of Joseph Goebbels, the bloody streets of Moscow during the October Revolution, a road accident, Rodin’s ‘Thinker’, Charles Baudelaire, a sparring rhinoceros.

‘My photographs are very damaged by people walking over them and crumpling them, and this does add implications to an image.’

As Bacon endeavoured to capture the essence of a particular individual, as he reimagined a singular identity, he merged the image of his subjects with those of his friends and lovers; with his own image and with his reference material. Consequently, his unsettling portraits straddled the divide between distortion and likeness; between fiction and fact.

In seeking to get closer to his subjects, he stood farther away.

‘I would like my pictures to look as if a human had passed through them, like a snail, leaving a trail of human presence and memory trace of past events as the snail leaves its slime.’

'Something small falls out of your mouth and we laugh.

A prayer for something better.

A prayer for something better.

Please love me, meet my mother.

But the fear takes hold,

Creeping up the stairs in the dark.

Waiting for the death blow,

Waiting for the death blow.

Over and over,

We die one after the other.

Over and over,

We die one after the other.

One after the other, one after the other.

It feels like a hundred years,

A hundred years, a hundred years.’

The Cure, ‘One Hundred Years’ (L Tolhurst / R Smith / S Gallup)

No. 498