After Impressionism: ‘Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?’

Edouard Vuillard Portrait of Lugne-Poe 1891

Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester (New York)

I recently attended ‘After Impressionism,’ an excellent show tracing the development of modern art between the last Impressionist Exhibition of 1886 and the outbreak of the First World War. (The National Gallery, London until 13 August)

The exhibition considers how artists at the dawn of the twentieth century were inspired by the Impressionist spirit of revolution and renewal; and how innovative creative thinking subsequently blossomed across Europe in new cultural hotspots - Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels and Vienna.

Impressionism was characterised by the quest to capture the fleeting moment; the reality of the world around us - with swift strokes of the brush and colours true to the artist’s experience.

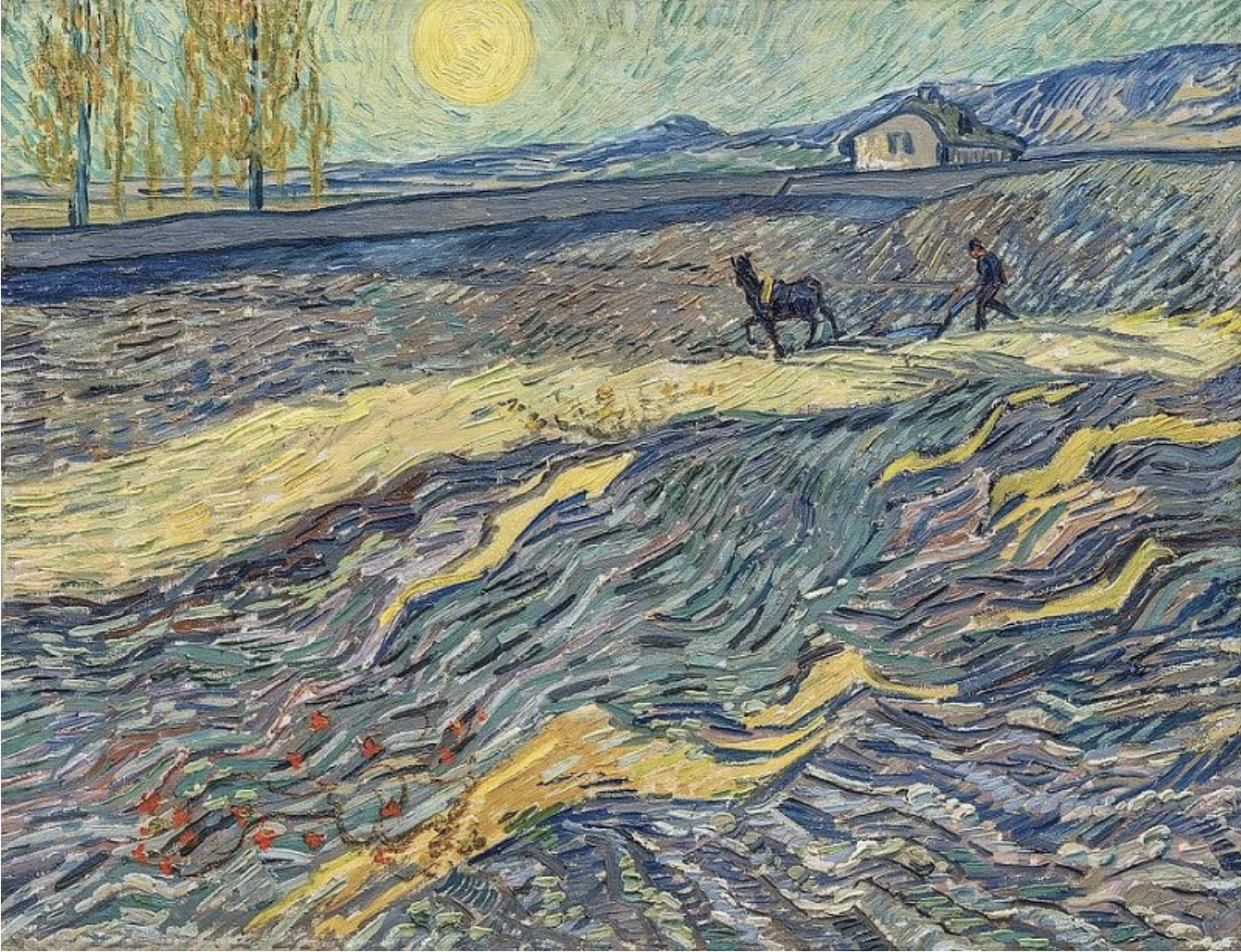

In the wake of this radical movement, Cezanne explored the underlying structures in nature - in landscape, portrait and still life – applying planes of colour that laid the foundations of Cubism. Gaugin went beyond representation of the natural world, using symbolism to convey personal memories and mystical experience. Van Gogh employed bold outlines and ever more intense hues that were charged with emotion. Seurat turned to science to translate light into colour through small dots of complimentary tones. Bonnard and Vuillard flattened their images, giving tranquil domestic scenes a decorative quality.

Vincent Van Gogh - Enclosed Field with Ploughman, 1889

During this period artists looked beyond Europe for inspiration, drawing on Japanese woodblock prints, Polynesian carved objects and African masks.

The creative community thought deeply and debated avidly about the direction they should take with their work. Artists conferred with like-minded modernist writers and formed groups with cool names like the Twenty, the Prophets, the Wild Animals and the Secession. They wrote essays and published journals; held dissident exhibitions and launched radical manifestos.

‘We are tired of the everyday, the near-at-hand, the contemporaneous: we wish to be able to place the symbol in any period, even in dreams.’

Gustave Kahn ‘La Response des Symbolistes’

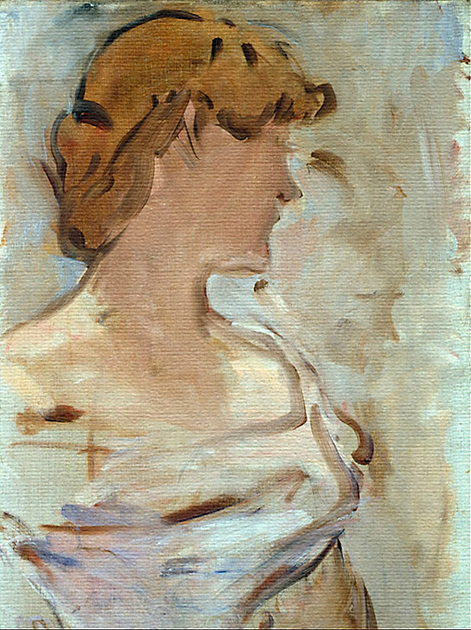

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - Combing the Hair ('La Coiffure'). National Gallery, London

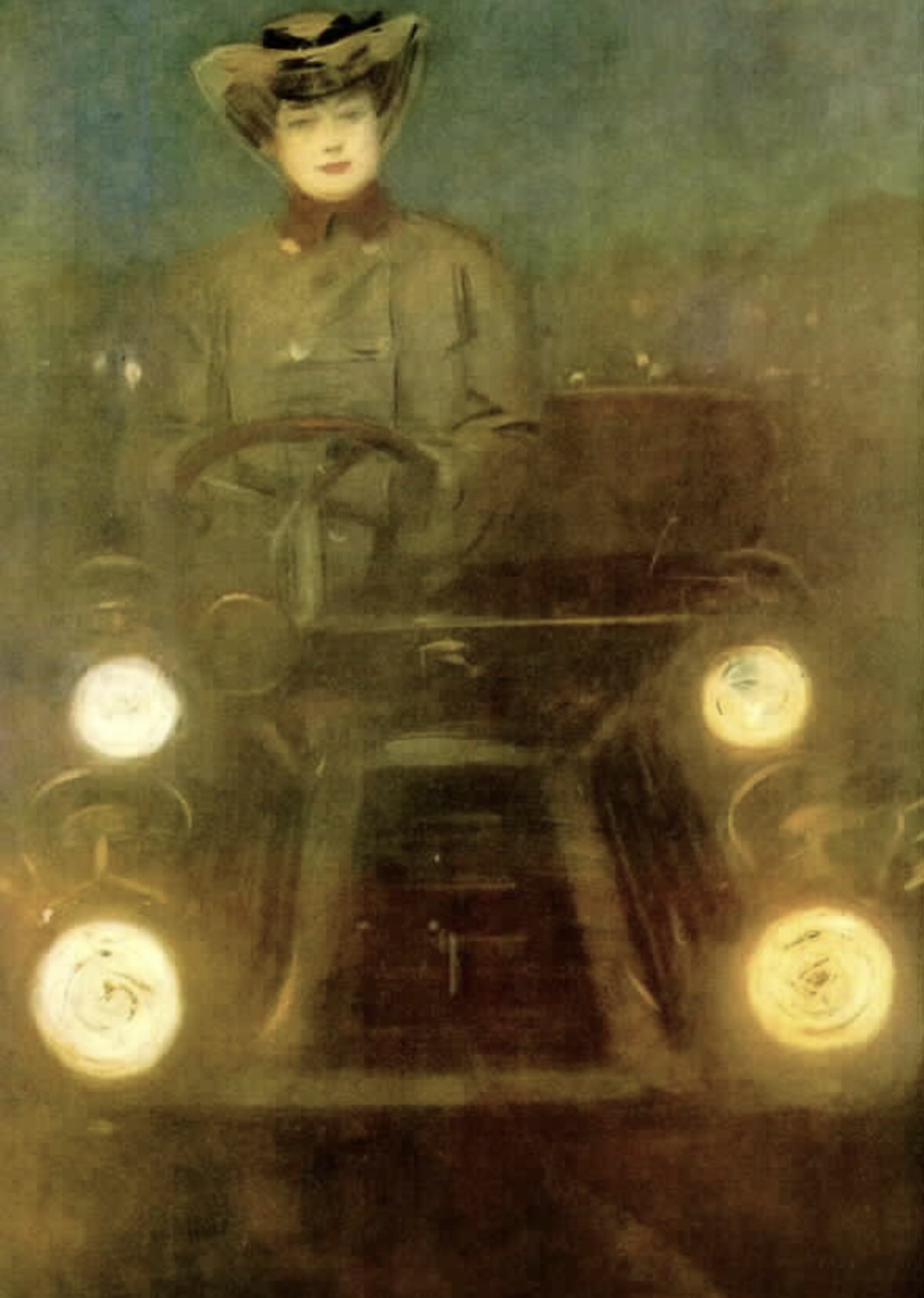

The result of all this upheaval and questioning was a period of stunning creative output, diverse in style and approach. At the exhibition you can see Cezanne’s ‘Mont Sainte-Victoire’, a majestic landscape reduced to geometric shapes; Klimt’s ‘Hermine Gallia’, a society lady shimmering in white chiffon; Degas’ ‘Combing the Hair’, an intimate moment all aglow with intoxicating orange. Gaugin presents us with the patriarch Jacob wrestling with an angel, observed by bonneted Breton women. It’s a woozy, dreamlike image. Munch’s ‘Death Bed’ reveals grief in the raw. Mondrian races towards Abstraction before our eyes. And in Ramon Casas’ ‘The Automobile’ an elegant woman drives a car directly at us, headlamps blazing. It is as if she is hurtling towards the future.

‘With faith in growth and in a new generation of creators and those who enjoy art, we call all young people together, and as the young that bear the future within it we shall create for ourselves elbowroom and freedom of life as opposed to the well-entrenched older forces. Everyone who renders directly and honestly whatever drives him to create is one of us.’

German Expressionist Manifesto

Ramon Casas i Carbó - Car. 1902

The exhibition suggests that people working in the creative industries should be arguing, discussing and debating ideas. We should be pioneering new perspectives and practices; experimenting with new partners and inputs.

It prompts us to reflect on our craft: Can we describe what makes our work different? What defines our generation’s outlook and output, in contrast to what has gone before?

One of Gaugin’s paintings of 1897-8 was entitled ‘Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?’ Perhaps we should be asking the same questions.

'If you could read my mind, love,

What a tale my thoughts could tell.

Just like an old time movie

About a ghost from a wishing well,

In a castle dark or a fortress strong,

With chains upon my feet.

You know that ghost is me

And I will never be set free.

As long as I'm a ghost, you can't see.’

Gordon Lightfoot, ‘If You Could Read My Mind'

No. 423