Hedy’s Hidden Talent: Considering Untapped Resources at Work

‘The brains of people are more interesting than the looks, I think.’

Hedy Lamarr

I recently saw a fine documentary plotting the extraordinary life and hidden talent of the film star Hedy Lamarr (‘Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story’, 2017).

Hedwig Kiesler was born into a middle class family in Vienna in 1914. She dropped out of school to become an actor, and in 1930 made her first film. In 1932 she gained notoriety when she appeared nude in ‘Ecstasy’, a movie that was banned in the United States. That same year she married a wealthy munitions manufacturer. Her jealous husband put her career on hold, and she found herself playing the society hostess, often to fascist military figures.

Kiesler was bored. She resented being controlled, and, being of Jewish descent, she felt unsafe. In 1937 she escaped by spiking her attendant’s tea and donning a maid’s outfit that had her jewelry sewn into its lining.

Kiesler arrived in London just when film mogul Louis B Mayer happened to be in town talent spotting. He offered her a modest $125 a week. She turned him down, but followed him to America and negotiated a $500 a week contract on the transatlantic crossing.

Mayer changed Kiesler's name to Hedy Lamarr and she made her Hollywood film debut alongside Charles Boyer in ‘Algiers’ in 1938.

Boyer: ‘What did you do before the jewels?’

Lamarr: ‘I wanted them.’

With her full lips, dark hair and distinctive centre parting, Lamarr was a hit with the American public. Her looks inspired Disney’s Snow White and DC Comics’ Catwoman. However, she was generally type cast as a glamorous seductress in exotic adventure epics. And she was rarely given interesting lines.

'I am Tondelayo. I make tiffin for you?'

Lamarr grew bored of Hollywood.

‘Any girl can look glamorous. All she has to do is stand still and look stupid.’

She had a curious mind. At the age of 5 she had taken a music box to pieces to see how it worked. Without any formal training, she liked to spend her spare time inventing at home or in her trailer on-set. She set about designing a traffic stop-light, a soluble cola tablet and aerodynamic plane wings.

‘I don’t have to work on ideas. They come naturally.’

In 1940, eager to help the war effort and concerned about her mother who was still in Europe, Lamarr was taken with a news report that suggested British torpedoes were being easily intercepted by the Germans.

‘I got the idea for my invention when I tried to think of some way to even the balance for the British… They shot the torpedoes in all directions and never hit the target. So I invented something that does.’

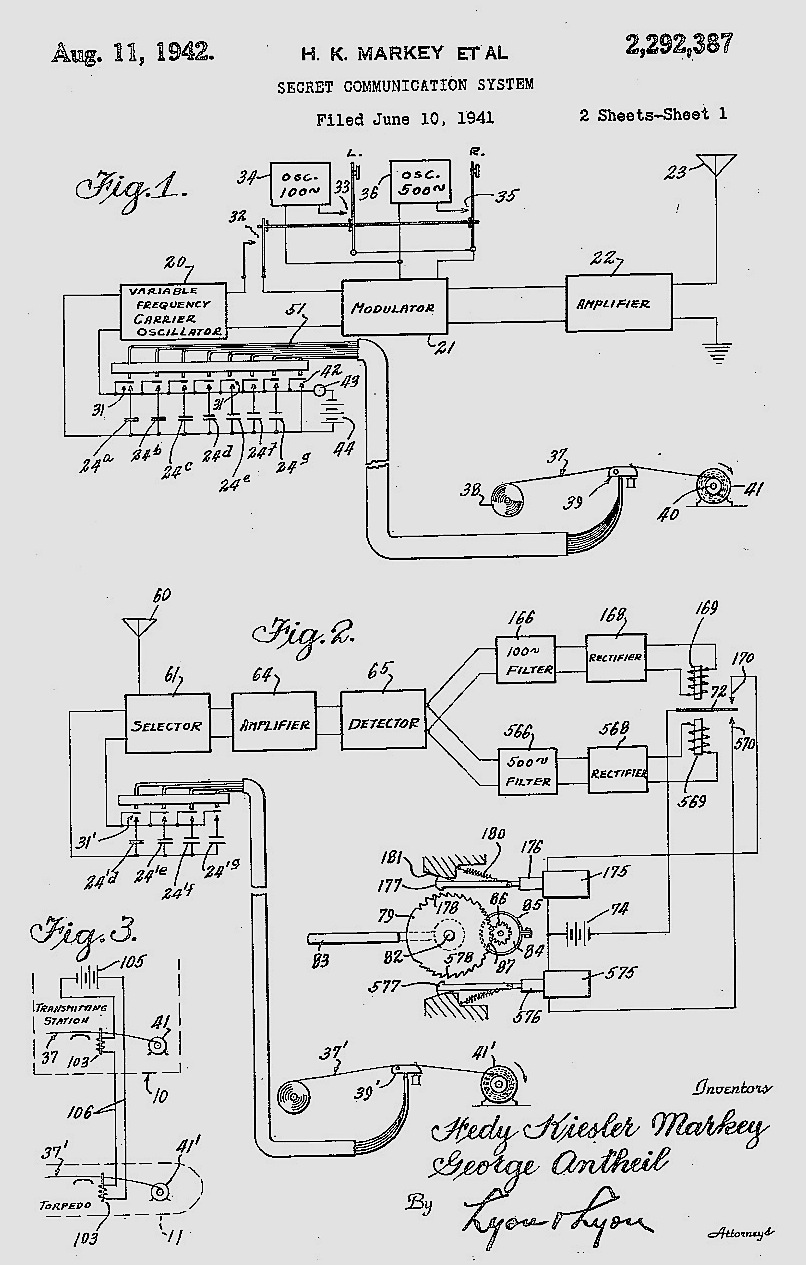

Lamarr teamed up with fellow amateur inventor, the composer George Antheil, and, inspired by early radio remote controls and the paper rolls used in player-pianos, together they developed the idea of a frequency-hopping system for remotely controlling torpedoes.

In 1942 the invention was patented, reviewed by the National Inventors Council and filed away in secret. It wasn’t taken up initially and Lamarr assumed it remained neglected. But the patent was revisited by the military after the war, and in the late '50s the concept was employed in the development of drones. Frequency hopping radio subsequently became the basis for today’s WiFi and Bluetooth technologies.

Sadly, there was no happy ending to this particular movie. Due to the expiration of the patent and Lamarr's ignorance of the time limits for filing claims, she made no money from her invention. In her later years, addicted to pills and plastic surgery, she withdrew to Florida and cash-strapped seclusion. She died in 2000.

What can we learn from Lamarr’s story?

Well, first of all perhaps that when we are bored and restless, we should resolve to do something about it.

'I can excuse everything but boredom. Boring people don't have to stay that way.'

Lamarr demonstrated a phenomenal curiosity and appetite for adventure. She followed her passions.

‘All creative people want to do the unexpected.’

Throughout her life she also exhibited a determination to overcome the obstacles that came in her way.

‘When things don’t come easy, figure out why, and then do something about it…And if people walk over you, don’t let them.’

This determination was particularly required in Lamarr’s engagement with men. She was married six times and was generally frustrated in love.

'Perhaps my problem in marriage - and it is the problem of many women - was to want both intimacy and independence. It is a difficult line to walk, yet both needs are important to a marriage.’

So, Lamarr teaches us to use boredom as a prompt to action, to follow our passions, and to be resolute in their pursuit. But above all she compels us to reflect on hidden talents: on skills that are unappreciated, underutilised, unrealised.

In the commercial sector, where it is increasingly difficult to develop and sustain genuine product differentiation, talent is often all we have to set a business apart. And a primary role of leadership is realising the value of the human capital that is available to it.

But how well do we know our own talent? How well do we understand our colleagues’ private passions and undisclosed gifts? Do we audit their skills and abilities? Have we ever set out to realise them?

It is not uncommon for leaders nowadays to proclaim to their workforce that they want them to be the best that they can be. But these are hollow words if no effort is taken to discover what people are best at.

Historically it has been the imperative of business to channel talent against a particular task or output. In the digital age surely we must be seeking, not just to harness ability to predetermined goals, but to follow talent wherever it takes us.

And of course, this applies as much to individuals as it does to organisations. Fulfilment at work begins with self-awareness. What am I good at? What are my special skills? What do I enjoy? What gives me a particular thrill?

Like Lamarr, once we have answered these questions, we should embrace their consequences, and pursue the unknown with enthusiasm and determination.

What have we got to be scared of?

‘Hope and curiosity about the future seemed better than guarantees. The unknown was always so attractive to me... And still is.’

No. 187