The Interdependent Business: The Networked Age Needs Networking Skills

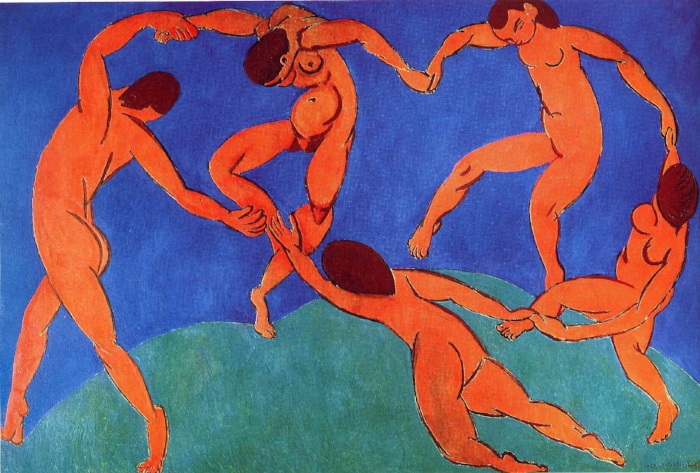

Henri Matisse 'La Danse'

My father was always very comfortable in the pub. At home he could be pensive, silent and self-absorbed. For hours he’d be sunk into his capacious armchair, the Telegraph on his lap, darts on the telly, black Nescafe and Embassy cigarettes within arm’s reach. But down the Drill Dad was gregarious and outgoing. He would perch on a high stool at the bar, cradling a pint of bitter in a dimpled jug, his change spread before him on a beer towel. He’d hold court on politics and popular culture, the decline of the British Empire and West Ham United. He’d chat for hours to Julian the barman, to Barry Green the market trader, and to Fat Mick who worked in a back office in the City. He’d talk to anyone in fact who was prepared to listen.

Dad once explained to me that the pub wasn’t just a place to socialise; it was a place to do business. ‘Anything that needs doing, you can do it down the pub.’ It was there that he arranged baby-sitting duties for Martin and me; there that he bought the family fitted floral chair covers, a food mixer and a second-hand car.

Perhaps, if the term had existed back then, you’d have said my father was a natural networker.

Some years later, by a curious set of circumstances, I found myself in a small seminar surrounded by modern-day Titans of Industry. I’d never been so close to so many important business people at one time and I thought this might be an ideal opportunity to understand what they had in common.

They were all rather charming actually. They were good storytellers, self effacing, easygoing. (I remember one of them made a joke about his neighbours. It was the kind of anecdote anyone would tell. These neighbours just happened to live on the adjacent island.) I’d not say these Titans of Industry were intellectuals as such. They did not demonstrate some extraordinary insight into world affairs. But they did share a broadly positive outlook, an inner confidence and an admirable ability to reduce matters to simple terms.

There was one unifying characteristic that really impressed me. When in the course of the seminar there was a need to get something done, one of the Titans would chime in with ‘I know such-and-such. I’ll reach out to such-and-such. They’ll point us in the right direction. They’ll sort this out. I’ll get them on the phone now.’

It struck me that a critical determinant of these modern entrepreneurs’ success was their supreme networking skills. Their inclination was never to embark on a task on their own. It was always to enlist like-minded expertise and specialism; to speculate on who could accelerate the process, ease the path, open the right doors.

In the past the preeminent skills of the entrepreneur may perhaps have been empathy and anticipation; innovation and independence; drive and determination. In the past it may all have been about self-belief and self-sufficiency. But in the digital era, business is so complex that the self is not sufficient. If you can confidently connect, you can achieve more in less time at lower cost; you can act with agility. The contemporary businessperson needs to be expert in partnership and participation, in collaboration and coordination. In the networked age, we all need to be networkers.

I say this with some reluctance because I have never been a great networker myself. I’m socially awkward, uncomfortable with business conversations that lack a defined purpose. I can connect ideas, but not people. And I squirm when I see an agenda indicating ‘there’ll be ample time for networking.’

But then again, perhaps we have devalued the term ‘networking.’ It has come to mean clumsily swapping business cards, tentatively checking profiles on LinkedIn. It’s become forced enthusiasm, cheap white wine and a casual Costa coffee. The networking that the modern world really demands is about connecting and combining talents to achieve commercial goals; to get things done, better, faster and more affordably. It’s about delivering a better service, not a better CV.

I was fortunate to work for many years in a successful independent business. We were proud of the fact that we were masters of our own destiny. But in a sense no business can be truly independent in today’s world. Nowadays we all depend on our allies and associates, suppliers and service providers. The best modern businesses are interdependent businesses.

Inevitably over recent years the response of the large corporates to the fragmenting service sector has been to merge and acquire; to buy out and buy in; to try to own everything. They see the ultimate destination as a full service offer, a ‘one-stop shop.’ But the corporate instinct to own and control suggests a failure to comprehend the mercurial demands of today’s world. Which Agency can comfortably manage the requirement for many services sometimes and few at others? Which Client wants to work with a partner who’s good at everything, but great at nothing? Ownership may be too rigid an answer.

In his book The Empty Raincoat Charles Handy, the Irish business philosopher, explored the theme of ‘the Chinese Contract.’ He related how, many years ago, when working in the oil industry in Malaysia, he was negotiating with a Chinese agent. They ‘reached terms, shook hands and shared a glass of brandy.’ But then when Handy brought out the official company contract and invited the Chinese agent to sign, the agent was incensed. For him this formalisation of the agreement betrayed a lack of trust and prompted suspicion that he was being locked into an unequal deal.

We need to rethink our approach to business relationships. Partnership is about trust and confidence, not liability and contracts. It is about open and honest collaboration, not reluctant and forced obligation.

The sadness for me is that my father was perhaps a man out of time. In another era his networking skills could have made him a Titan of Industry. As it was, despite his natural charm and ability to connect, he was not actually very successful in business. He drifted, amiably but aimlessly, from travel agency to double-glazing to the gasket sector. One winter the car he bought from the bloke in the Drill completely broke down because he had failed to top up the anti-freeze. But it didn’t seem to matter too much to Dad. He just found another bloke to fix it down the pub.

"Love is a rose

But you better not pick it.

It only grows when it’s on the vine.

A handful of thorns and

You’ll know you missed it.

You lose your love when you say the word ‘mine.’’

Neil Young, Love Is a Rose

This piece has just been published in the Spring 2017 edition of You Can Now magazine.

No. 125