‘Baby, I Don’t Care’: Don’t Let a Service Business Become Servile

‘You know you can’t act. And if you hadn’t been good looking, you would never have gotten a picture.’

Katharine Hepburn to Robert Mitchum

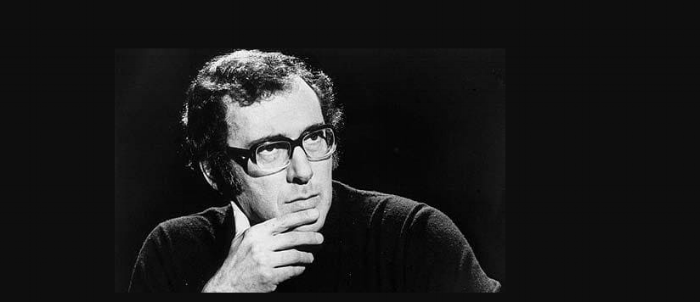

Many were rather dismissive of Robert Mitchum’s acting talent. They found him passive, wooden, flat. He often seemed to lack emotional engagement and occasionally he gave the impression that he wished he was somewhere else. Of one performance a journalist wrote that ‘he moved as if on casters.’ He never won an Oscar.

Mitchum himself wasn’t inclined to disagree. He dismissed his own acting ability with cheery indifference.

‘I got three expressions: looking left, looking right and looking straight ahead.’

Throughout his career Mitchum would take on parts he knew were poorly written and undemanding.

‘Movies bore me, especially my own.’

Asked what he looked for in a script before accepting a role, he said: ’Days off.’

Some have observed that Mitchum found it hard to take acting too seriously because his childhood had been so challenging. A year or so after his birth (in 1917 in Bridgeport, Connecticut) his rail-worker father was crushed to death in an accident at the yard. Frequently expelled from school, the young Mitchum found himself riding railroad cars, picking up odd jobs where he could. When he was 14 he was arrested for vagrancy and put to work on a chain gang.

So maybe Mitchum had good reason to make light of his craft.

And yet, in amongst all the uninspiring westerns and production-line romances, Mitchum starred in some of the finest films of the 1940s and ‘50s. Classic noirs like ‘Crossfire’ and ‘The Big Steal’; sinister thrillers like ‘The Night of the Hunter’ and ‘Cape Fear.’

Over the years critics reassessed Mitchum.

‘People can’t make up their minds whether I’m the greatest actor in the world – or the worst. Matter of fact, neither can I.’

In his best work Mitchum had a quiet charisma, a cool naturalism. With his heavy-lidded look and minimal movement - often wearing the same worn-out trench coat - he displayed an air of bitter experience and careless nonchalance. He could suggest both vulnerability and menace. Beside him other actors seemed to try too hard, to over-emote; and thereby to lose something of their authenticity. Commentators began to recognise in him someone for whom less was more. They celebrated him for ‘being, not acting.’

In the 1947 masterpiece ‘Out of the Past’ Mitchum plays Jeff, an ex-private detective who can’t escape his past and the charms of Kathie, his faithless former lover. In one scene Kathie, played by Jane Greer, begs to be believed one last time:

‘I didn't take anything. I didn't, Jeff. Don't you believe me?’

Mitchum gives Greer a weary look and a knowing embrace, and says: ‘Baby, I don't care.’

I wonder whether the communications industry could learn something from Mitchum, the movie star who won out through under-acting; through dialing it down; through seeming not to care too much.

Ours is a culture whose currency is passion and positivity. We have no red lines, only green. Show us an extra mile and we’ll run it. Show us a hoop and we’ll jump through it.

But sometimes our enthusiasm diminishes our seriousness; our readiness to offer alternatives smacks of a lack of commitment; our willingness to move on compromises the integrity of our recommendations; our eagerness to go again betrays a disregard for the personal lives of our colleagues.

Back in the day Nigel Bogle would warn of the perils of a service business becoming servile: ‘The answer’s ‘’yes.’’ What’s the question?’

So what do you think?

Are we too eager to please, too desperate to win? Does our commitment to do ‘whatever it takes’ devalue our output, overload our staff, constrain our finances, compromise our values? Are we just too keen?

Surely we should commit, not to ‘whatever it takes’, but to ‘whatever is right’ - for the task, for the brand, for the time, for the fee. And be prepared - just occasionally - to walk away.

Easier said than done, I know, in an oversupplied, highly competitive, cost-constrained market; in a world of tied relationships and trigger-happy Clients. But, as the mystery slips, as margins slide and motivation sags, the industry will have to take a stand one day.

Perhaps we should heed Robert Mitchum’s advice:

‘There just isn't any pleasing some people. The trick is to stop trying.’

No. 171