NOTES FROM THE HINTERLAND 10

If Music Be the Food of Commerce…

Claire van Kampen’s magnificent play, Farinelli and the King, relates how, in the mid-eighteenth century, Philippe V of Spain hired the renowned castrato Farinelli to sing for him so as to sooth his frequent bouts of depression. The king and performer struck up a close relationship and the commission lasted until Philippe’s death almost ten years later.

Farinelli and the King is funny, sad and thought provoking all at the same time. It is graced by the peerless actor, Mark Rylance, and the celebrated counter-tenor, Iestyn Davies. It runs at the Duke of York’s Theatre until December 5.

As the play’s programme notes point out, ‘the therapeutic value of music has been recognised for centuries.’ Apollo was the Ancient Greek god of medicine as well as music. Music therapy was practised in Ancient Egyptian temples and Persian hospitals. Subsequently music treatments were adopted by medieval infirmaries and were used extensively in two World Wars. Today music therapy is a widely practised and respected medical science.

‘Music has been shown to significantly decrease the levels of the stress hormone cortisol, leading to improved mood and cognitive function. A study has also found that music can shift activity in the frontal lobe of the brain from the right to the left, a phenomenon associated with positive effect and mood.’

Dr Tim McInerny, Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist, Bethlem Royal Hospital

For many of the same reasons that music has therapeutic effect, it also has commercial effect.

For most of the ‘90s I worked on the Levi’s advertising campaign and it created a compelling case for the commercial capacity of music: to engage audiences; to convey an emotional narrative; to create memorability and distinctiveness.

Of course, everyone nowadays claims to appreciate music’s persuasive power. But, I wonder, does everyone properly understand how to realise that power?

Some imagine that music selection is merely a matter of sourcing a cool, contemporary track. But young consumers don’t thank you for hijacking tunes they already love. In recent years some have followed John Lewis down the ‘modern acoustic version of familiar songs’ route. But, as Oscar Wilde said, ‘imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity can pay to greatness.’ Some imagine there’s a spurious science to sourcing tracks. Some think it’s just about buying hits. Some will agree to music’s importance, but balk at its cost, thereby betraying their lack of faith.

Fundamentally, I believe that music selection must be a creative decision, not a strategic one. It’s not about matching the music to the target audience; it’s about matching the music to the creative work: capturing the spirit and tone of the drama; allowing the narrative to unfold at the right pace and tempo; enabling consumers to feel the message, not just see it or hear it.

Music should amplify the communication, not stand in its way. If you get that right, then you’ll find an audience; and it will be an audience that is properly emotionally engaged.

‘Musick has charms to sooth a savage breast,

To soften rocks, or bend a knotted oak.

I’ve read, that things inanimate have mov’d

And, as with living souls, have been inform’d,

By magick numbers and persuasive sound.’

William Congreve, The Mourning Bride

Synthesized Success

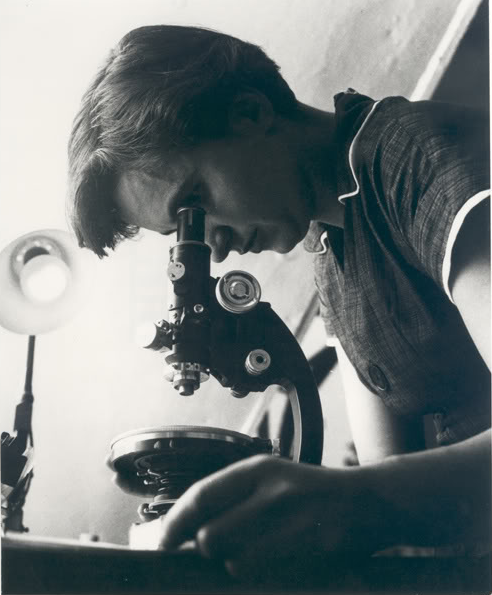

Young songwriter Neil Sedaka was in a jam.

Though his mother hoped that he would become a classical pianist and he had a scholarship at the Juilliard, all he wanted was to write and perform pop songs. Sedaka had composed ‘Stupid Cupid’, which had been a hit for Connie Francis in 1958. That same year he’d signed to RCA Victor as a performer, and had a hit with ‘The Diary’, which sold 600,000 copies. But Sedaka’s two subsequent releases were failures and his record company was considering dropping him. He had one last chance.

‘Billboard had a page called Hits of the World. I bought the number one record in almost every country in the world and analysed it. I took the beat from this one; I took the drum from this one; I took the guitar licks from this one; I took the harmonic rhythm from this one. Like a designer would do.’

Neil Sedaka, King of Song/ BBC

The result was ‘Oh! Carol’, a melodic triumph of sweet-natured youthful yearning. It sold 3.5million copies.

‘Oh! Carol

I am but a fool

Darling, I love you

Though you treat me cruel.’

‘Oh! Carol’/Howard Greenfield & Neil Sedaka

Sedaka went on to secure huge pop hits in the ‘60s with the likes of ‘Happy Birthday, Sweet Sixteen’ and ‘Breaking Up Is Hard to Do.’ And then he sustained the success in the ‘70s with the genius of ‘Solitaire’ and ‘Laughter in the Rain.’

Of course, we’re always seeking to be original. But sometimes commercial creativity requires us to be alert to the competitive context, to what works and what doesn’t. Sometimes, when we’re in a jam, we need to beg, borrow or steal.

Synthesizing one’s own success from the successes of others is a skill in its own right.

Creativity Can Even Survive Rate Card Pricing

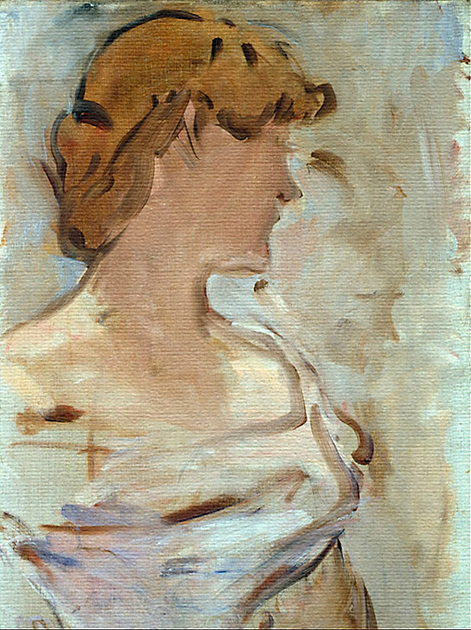

On a recent visit to Chicago I encountered The Entombment by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri. Painted around 1656, it’s a sad, beautifully naturalistic depiction of death and despair.

The artist is more familiar to us as ‘Guercino’, or ‘The Squinter’, a nickname given to him because he was cross-eyed. Guercino kept relatively detailed account books and we know that The Entombment was his response to a commission that required ‘one full length, one bust length and three half figures.’

We can see that Guercino ably accommodated this rather prescriptive brief, whilst also delivering a very engaging image. This perhaps illustrates that creativity can survive even the crudest pricing policy.

No. 55