Phaedra: A Life of Surprises

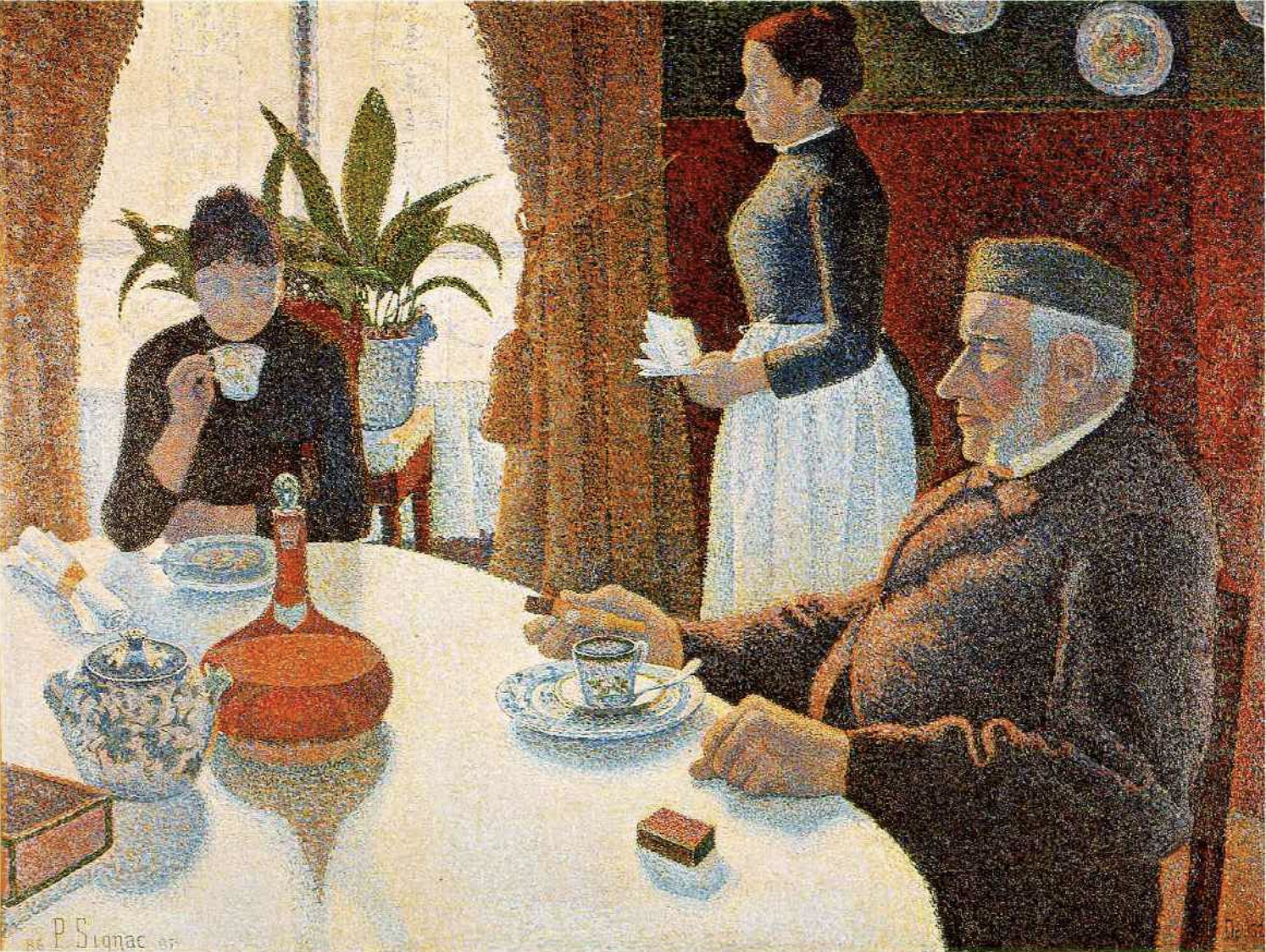

Alexandre Cabanel - Phaedra, 1880. Oil on canvas. Musée Fabre, Montpellier

As I took my seat at the National Theatre, I was surprised to see a stylish young couple settling in next to me.

We had bought tickets to see the classical work Phaedra. This would typically be the domain of quarter-zips and blazers, the floral midi-dress and white trainers; of fleece, grey hair and walking-sticks.

I was concerned that the stylish young couple would find this ancient Greek tragedy about a woman who falls in love with her stepson hard going.

Nonetheless, as the lights went down, I hoped for the best.

The production was a modern ‘re-imagining’ of the Phaedra story by Simon Stone, drawing on versions by Euripides, Seneca and Racine. (This was 2023. It’s not on-stage now, I’m afraid.)

Helen (Phaedra), a charismatic politician, convenes a meal with her husband, teenage son and married daughter. They are visited by Sofiane, the son of Helen’s former, now dead, lover.

Sofiane blames Helen for stealing his father away from his mother, and believes their affair led to his death. He has fantasised about Helen since childhood, and she, dissatisfied with her marriage, falls for him, recognising a strong resemblance to her lost partner.

I sensed at the interval that the drama had engaged the couple next to me. It was complex, psychologically nuanced, unpredictable. Would Helen turn out to be a hero, villain or victim?

But then the plot took a further twist. Sofiane embarks on another affair – this time with Helen’s daughter.

At this point the young woman next to me was startled. She extended her hands in front of her and audibly exclaimed: ‘What the actual f**k!’

I would not normally approve of audience participation of this sort. But it was such a natural, spontaneous response. She was genuinely shocked.

'There are two kinds of taste, the taste for emotions of surprise and the taste for emotions of recognition.'

Henry James

I was pleased that a classical play, albeit a modern version, could provoke such a reaction. But of course. Greek tragedy concerns itself with fate and free will; with pride and desire, violence and vengeance; with flawed heroes coming to terms with their weaknesses and mistakes. The plots would comfortably adapt to contemporary Netflix dramas.

‘The element of surprise is the most important thing and what keeps me interested in writing.’

Phoebe Waller-Bridge

We imagine that it’s difficult to disarm and unsettle contemporary generations. That they’re too knowing, cynical and worldly wise. That they’ve seen it all before.

But if you set the right context for an audience and lull them into a false sense of security; if you manipulate their assumptions, suggest the plot is going one way and then take it another, then it’s still possible to jolt people out of their seats.

And surprise remains one of the most potent tools in the storyteller’s armoury.

‘What the actual f**k!’

'Never let your conscience be harmful to your health.

Let no neurotic impulse turn inward on itself.

Just say that you were happy, as happy would allow.

And tell yourself that that will have to do for now.

Darling, it's a life of surprises.

It's no help growing older or wiser.

You don't have to pretend you're not crying,

When it's even in the way that you're walking.’

Prefab Sprout, ‘A Life of Surprises’ (P Mcaloon)

No. 550